Kaposi sarcoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma — two HIV-associated cancers — are less frequent, but still occur in patients undergoing antiretroviral therapy, according to a paper published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Chad Achenbach, ’02 MD, ’02 MPH, assistant professor of Medicinein the Division of Infectious Diseases, co-authored the study. Achenbach is also a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.

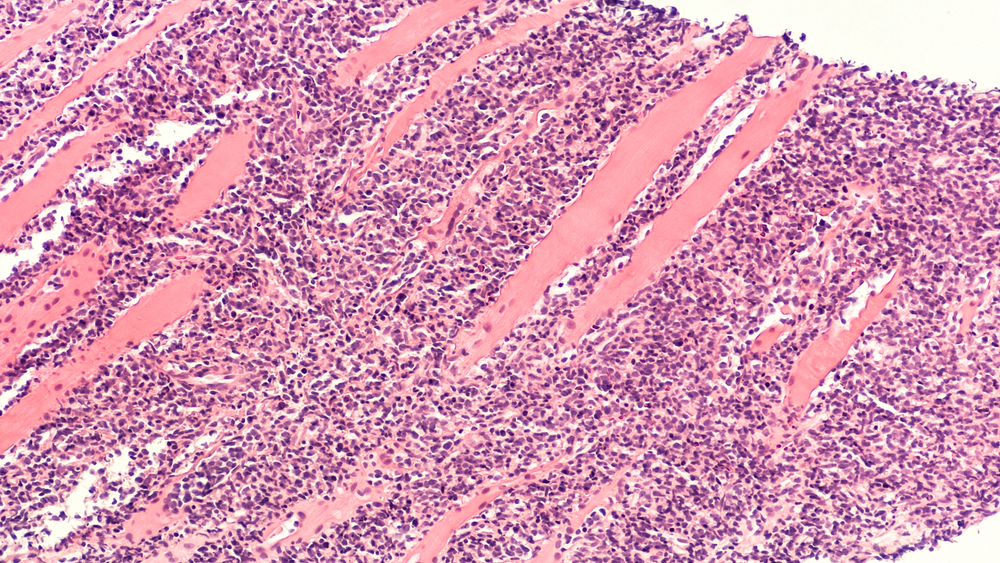

Patients with HIV are at a much greater risk for developing Kaposi sarcoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma because of a weakened ability to fight off other viral infections that may lead to these cancers. While the risk of these cancers has declined dramatically in recent decades thanks to antiretroviral therapy (ART) — medications which treat the HIV virus — the incidence nonetheless remains significantly higher than in the general population without HIV.

In the observational study, which included close to 25,000 patients with HIV, investigators examined data starting from 1996, when potent combination ART came into widespread use, until 2011. They found that, as expected, the incidence of Kaposi sarcoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma fell in the years after 1996.

But they also identified new trends in characteristics related to the diagnosis of these cancers. Over the course of the study, patients showed lower HIV RNA values and higher CD4 counts at the point of initial cancer diagnosis. A higher number of CD4 cells — white blood cells that fight infection — is typically a sign that the HIV virus is being controlled.

They also found that, over time, Kaposi sarcoma was more frequently diagnosed after a patient had initiated ART. (This wasn’t driven by an increase in the risk of cancer for patients on ART, but rather, by the growth in the portion of the HIV population receiving treatment.)

Overall, the investigators’ findings reveal that patients remain at risk for these HIV-associated cancers, even while responding well to HIV treatment.

The study also raises important questions for future research, including whether cases of Kaposi sarcoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma that develop during HIV treatment are biologically or genetically different from those that arise when HIV is uncontrolled with profound immune defects. If so, it could indicate a need for finding new approaches to preventing, identifying and treating these cancers.

“This paper shows us the importance of studying the changing epidemiology of HIV-associated cancer in the current era of potent HIV therapies,” Achenbach said. “Interactions between the immune system and cancer are amplified in those with HIV. This gives us an opportunity to understand how a defective immune system alters cancer risk.”