Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology and the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, have found several previously unknown genes that make bacteria resistant to last-resort antibiotics. The genes were found by searching large volumes of bacterial DNA and the results are published in the scientific journal Microbiome.

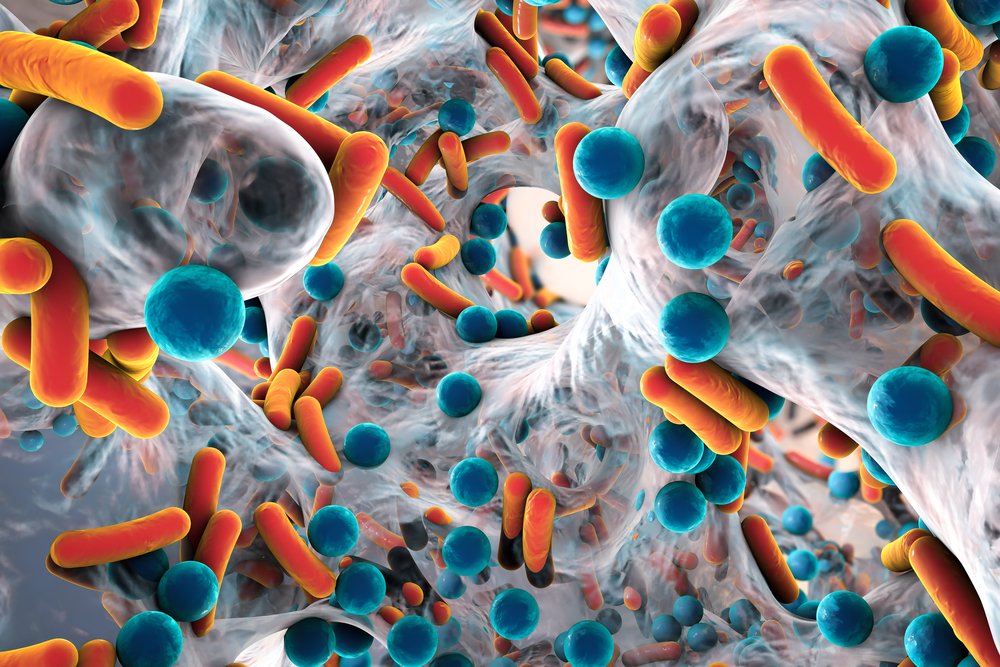

The increasing number of infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria is a rapidly growing global problem. Disease-causing bacteria become resistant through mutations of their own DNA or by acquiring resistance genes from other, often harmless, bacteria.

By analysing large volumes of DNA data, the researchers found 76 new types of resistance genes. Several of these genes can provide bacteria with the ability to degrade carbapenems, our most powerful class of antibiotics used to treat multi-resistant bacteria.

“Our study shows that there are lots of unknown resistance genes. Knowledge about these genes makes it possible to more effectively find and hopefully tackle new forms of multi-resistant bacteria”, says Erik Kristiansson, Professor in biostatistics at Chalmers University of Technology and principal investigator of the study.

“The more we know about how bacteria can defend themselves against antibiotics, the better are our odds for developing effective, new drugs”, explains co-author Joakim Larsson, Professor in environmental pharmacology and Director of the Centre for Antibiotic Resistance Research at the University of Gothenburg.

The researchers identified the novel genes by analysing DNA sequences from bacteria collected from humans and various environments from all over the world.

“Resistance genes are often very rare, and a lot of DNA data needs to be examined before a new gene can be found”, Kristiansson says.

Identifying a resistance gene is also challenging if it has not previously been encountered. The research group solved this by developing new computational methods to find patterns in DNA that are associated with antibiotic resistance. By testing the genes they identified in the laboratory, they could then prove that their predictions were correct.

“Our methods are very efficient and can search for the specific patterns of novel resistance genes in large volumes of DNA sequence data,” says Fanny Berglund, a PhD student in the research group.

The next step for the research groups is to search for genes that provide resistance to other forms of antibiotics.

“The novel genes we discovered are only the tip of the iceberg. There are still many unidentified antibiotic resistance genes that could become major global health problems in the future,” Kristiansson says.