Courtesy of the researchers

Thanks to a new design, scientists believe they have created a gallium nitride power device to handle voltages of nearly double of what conventional devices can handle.

Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), semiconductor company IQE, Columbia University, IBM, and the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology, have designed new vertical gallium nitride power devices that can handle voltages up to 1,200 volts.

“All the devices that are commercially available are what are called lateral devices,” Tomás Palacios, who is an MIT professor of electrical engineering and computer science, a member of the Microsystems Technology Laboratories, and senior author on the new paper, said in a statement. “So the entire device is fabricated on the top surface of the gallium nitride wafer, which is good for low-power applications like the laptop charger.

“But for medium- and high-power applications, vertical devices are much better,” he added. “These are devices where the current, instead of flowing through the surface of the semiconductor, flows through the wafer, across the semiconductor. Vertical devices are much better in terms of how much voltage they can manage and how much current they control.”

Recently power converts made from gallium nitride have begun to reach the market, boasting higher efficiencies and smaller sizes than conventional, silicon-based converters.

However, commercial gallium nitride power devices can’t handle voltages above approximately 600 volts, limiting their use in household electronics.

With lateral devices, all the current flows through a narrow slab of material close to the surface, where all the heat is generated.

In a vertical device, current flows into one surface and out the other, meaning that there is more space in which to attach input and output wires, which enables higher current loads.

In a vertical device, the current flows through the entire wafer where the heat dissipation is uniform.

Vertical devices are difficult to fabricate in gallium nitride because power electronics depend on transistors, devices in which a charge applied to a gate switches semiconductor materials between a conductive and a nonconductive state.

For that switching to be efficient, the current flowing through the semiconductor needs to be confined to a relatively small area, where the gate’s electric field can exert an influence on it.

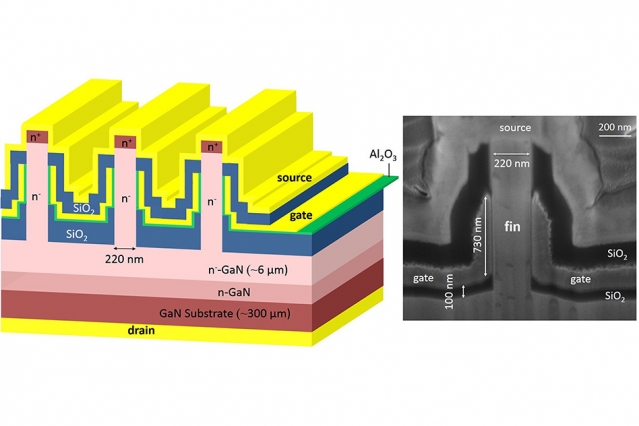

The new vertical gallium nitride transistors have bladelike protrusions on top, called fins, with electrical contacts on both sides of each fin that act as a gate.

The researchers believe that they eventually can further boost the capacity of the device to the 3,300-to-5,000 volt range.