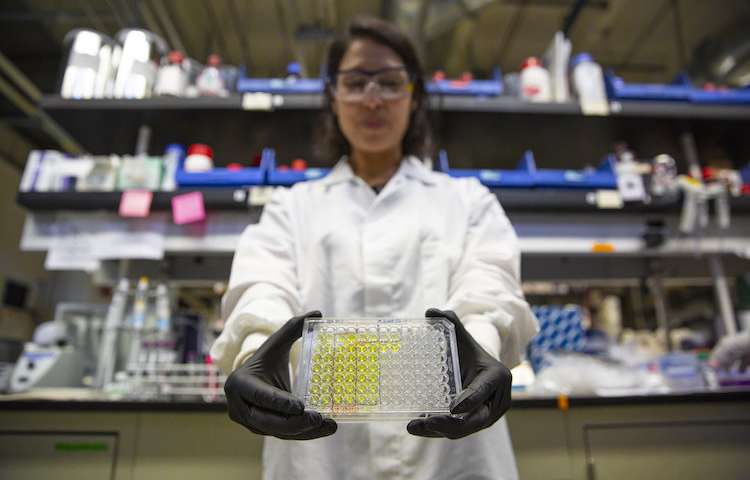

Tara deBoer holds a well-plate of synthetic urine samples that have been added to the DETECT solution. The solution turns yellow when antibiotic-resistant bacteria are present. Credit: Stephen McNally

Researchers from the University of California Berkeley have created a new test that can diagnose patients with antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria in only a couple of minutes, an innovation which could help doctors prescribe a specific antibiotic for each infection, limiting the spread of antibiotic resistant superbugs.

“Health organizations around the world are supporting the development of tools that specifically identify pathogens that are resistant to antibiotics because there are limited tests available that can do it quickly,” Tara de Boer, a postdoctoral fellow in the College of Engineering at UC Berkeley, said in a statement. “Our test is simple and gives us information on a short timescale.”

The new test—dubbed DETECT—is able to identify the molecular signatures of antibiotic-resistant bacteria directly in urine samples without needing expensive instrumentation. The test is also simple enough to be applied in a point-of-care setting.

“Drug-resistant infections are a silent pandemic that actually kill more people every year than Zika or Ebola,” Lee Riley, professor of epidemiology and infectious diseases in the School of Public Health at UC Berkeley, said in a statement. “The faster you can start the right drug, the better the chances of survival or avoiding complications.”

Several early generation antibiotics commonly used like penicillin, amoxicillin, and ampicillin are based on a beta-lactam molecular structure that blocks bacteria from building cells walls to make it impossible for microbes to grow and reproduce.

However, some bacteria like E. coli, Salmonella and Shigella, have evolved to produce beta-lactamases enzymes that chop up the antibiotics and render them ineffective. In the new test, the researchers are able to spot the presence of beta-lactamases in urine samples and tailor the prescription to overcome this problem.

Researchers have long known how to detect beta-lactamases, but the technique was not sensitive enough to identify the relatively small concentrations of beta-lactamases in patient samples. This forced researchers to culture bacteria from a patient sample in the lab first. This process could take two to three days, which could allow a simple bacterial infection such as a urinary tract infection enough time to invade the kidneys or the blood.

The new test uses an enzymatic chain reaction to boost the signal from beta-lactamases by a factor of 40,000, enabling doctors to detect its presence in urine samples.

To test DETECT, the researchers examined 40 urine samples collected from patients suspected of having urinary tract infections as part of the Consortium for Research on Antimicrobial Resistant Bacteria (CRARB).

The researchers found antibiotic-resistant infections in about 25 percent of the samples.

“DETECT tells you not only who has antibiotic-resistant infections but also tells you who could be treated by early-generation antibiotics, allowing you to spare higher-end antibiotics and slow the spread of drug resistance,” Niren Murthy, a professor of engineering at Berkeley, said in a statement.

The researchers are now working with doctors and clinical lab specialists to design DETECT devices that can be catered to specific medical settings.

The study was published in ChemBioChem.