Illustration: Johan Jarnestad.

Amid this week of Nobel Prizes, the annual award for Physics made history in honoring a trio for revolutionary gains in laser technology at the end of the 20th century.

The female laureate among the three is just the third to get the award, and the first woman in 55 years to be so honored. And, one of the other recipients is now the oldest Nobel Laureate in history.

Arthur Ashkin, who developed “optical tweezers” over his time while working for decades at Bell Laboratories in Holmdel, New Jersey, will get half the award, at age 96.

The other half will be split by Donna Strickland, of the University of Waterloo, and her former co-worker Gerard Mourou, now at the Ecole Polytechnique in France, for their development of chirped pulse amplification (CPA), a technique of harnessing high-intensity lasers.

Strickland was shocked to hear she was one of three women to win the physics prize (the first being Marie Curie in 1903, the last being Maria Goeppert Mayer in 1963).

“I thought there may have been more,” said Strickland this morning. “Obviously we need to celebrate women physicists because we’re out there. Hopefully, in time, it will start to move forward at a faster rate, maybe… I’m honored to be one of those women.”

Ashkin began working with lasers at Bell Labs in the 1960s. His observations and trials determined that the middle of the intense light beam drew microscopic particles to the center of the beam. Ashkin focused the light further with a lens, intensifying the effect. What started as a “light trap” eventually became known as “optical tweezers.” Eventually, Ashkin and colleagues refined the tool to be able to capture individual atoms in the 1980s; and that same decade, he managed to use an infrared beam to trap bacteria without harming them. Today, the tool is used in many laboratories worldwide, in innumerable experiments.

“Work on laser tweezers and laser manipulation started when I asked a simple question: Was it possible to move small particles by pushing on them with a laser light beam?,” said Ashkin in a speech given upon his winning the Israel-based Harvey Prize in 2004. “This effect is almost like science fiction to me, to this day. One can just focus a laser beam on a transparent sphere, you can trap it, you can pick it up, you can move it around, you can put it down… and for that obvious reason you can do all these things, it’s called laser tweezers.”

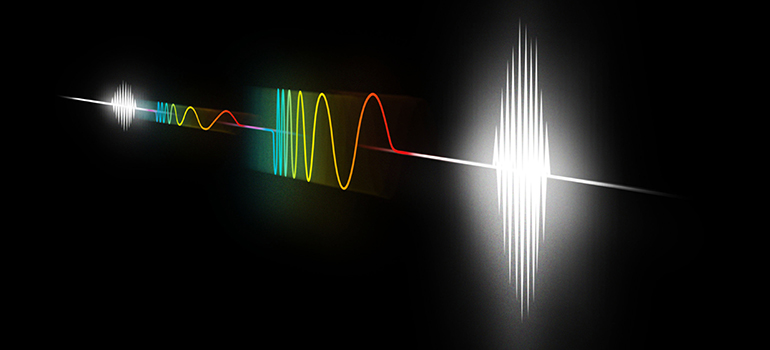

Strickland’s part in the award was made in December 1985, with the publication of her doctoral dissertation while at the University of Rochester. Mourou was her supervisor. Together, the two found a way to stretch a light pulse to reduce its peak power. But then the stretched pulse is amplified and compressed, intensifying its power. The Nobel Prize Committee described the work creating CPA as “both simple and elegant.” The high-intensity lasers are now used in eye surgeries, data storage and to investigate subatomic particles at resolutions never before realized.

“I was a Ph.D. student at the time,” Strickland told the Nobel presenters this morning, describing the scientific competition for the high-intensity laser breakthrough in the mid-1980s. “I think… it’s somewhat thinking outside the box to stretch first, and then amplify. Most people were amplifying and trying just to compress whatever they had amplified.”