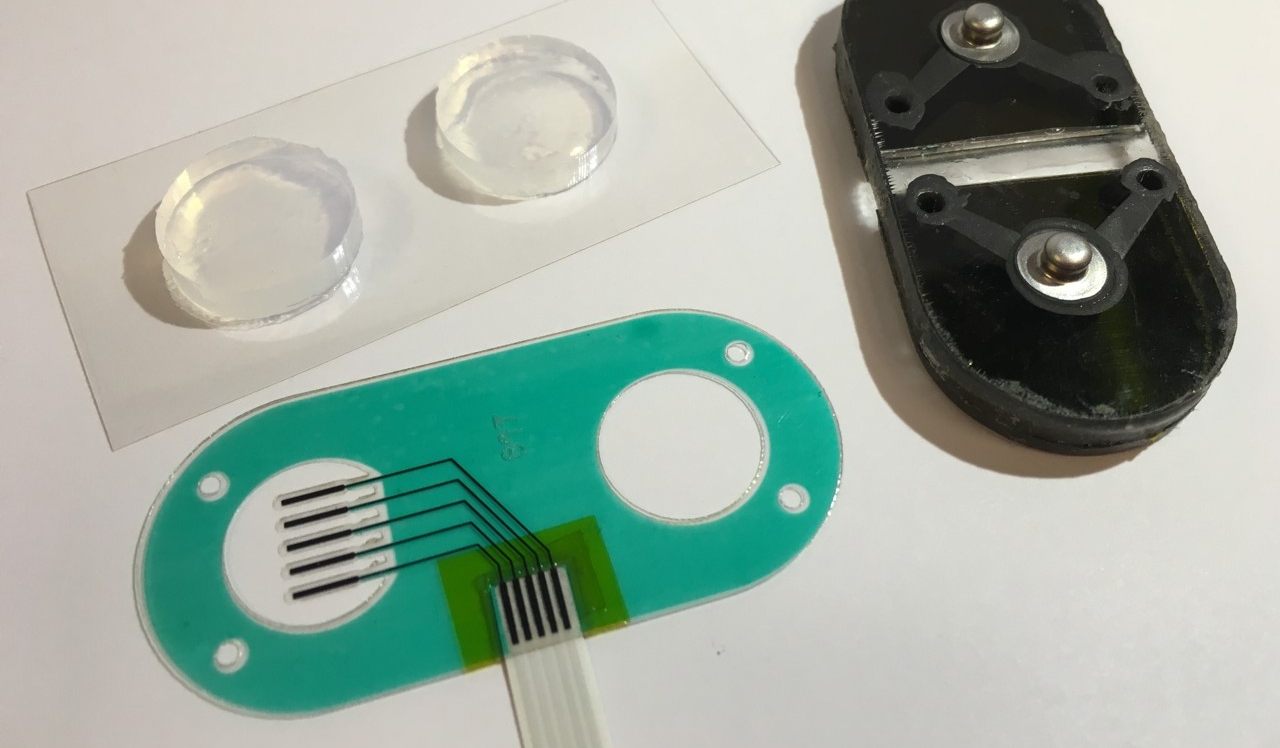

The UC study used a low electric current and carbachol gel to stimulate sweat under a sensor the size of a Band-Aid. Credit University of Cincinnati

No longer will you have to look like you just ran a marathon to use a biosensor that tests sweat.

Researchers from the University of Cincinnati have developed a new method to stimulate sweat glands on a small, isolated patch of skin, avoiding the need for patients to have to exert themselves to build up a sweat to go through biometric testing.

The device is the size of a small bandage and uses a chemical stimulant to produce sweat, even when the user is cool and relaxed. The sensors predict how much a patient will sweat, which professionals use to understand the hormones or chemicals the biosensors measure.

“The challenge is not only coming up with new technological breakthroughs like this but also bringing all these technology solutions together in a reliable and manufacturable device,” professor Jason Heikenfeld, said in a statement. “Doctors would love to know if chemical concentrations are increasing or decreasing over time.

“What was your baseline before you got sick? Then by measuring the change in concentrations, we know even more about how sick you are or how quickly you are getting better,” he added.

Biometric testing often focuses on blood, which is invasive and can require the use of a lab. However, sweat can provide just as much information as blood.

“People for a long time ignored sweat because, although it can be a higher-quality fluid for biomarkers, you can’t rely on having access to it,” Heikenfeld said. “Our goal was to achieve methods to stimulate sweat whenever needed — or for days.

“If you do a blood draw, you get one data point,” he added. “In many cases, doctors would love to know if concentrations are increasing or decreasing over time.”

To test the device the researchers applied sensors and a gel containing carbachol—a chemical used in eyedrops—to a user’s forearm for two-and-a-half minutes.

They obtained data through the gel and sensors alone and in combination with memory foam padding to provide better contact between the sensor and the skin. They also employed iontophoresis—an electric current at 0.2 milliamps that drives a small amount of the chemical into the upper layer of the skin and locally stimulates sweat glands while causing no physical sensation or discomfort.

The researchers measured concentrations of sweat electrolytes and found that carbachol was effective at inducing sweating under the sensor for as long as five hours.