A molecular signaling pathway identified by an international research team could be the basis of improved treatment for osteoporosis. In their report published in the online journal Nature Communications, the investigators describe how suppressing the activity of a specific enzyme not only increased bone formation in mice but also reduced levels of the cells responsible for bone breakdown. While one currently available treatment – injections of a fragment of parathyroid hormone (PTH) – can stimulate bone formation, it also stimulates the resorption of bone.

“We wanted to understand how PTH signaling affects gene expression within bone cells, particularly in osteocytes, which are buried deep within bone itself,” says lead author Marc Wein, MD, PhD, of the Endocrine Unit in the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Department of Medicine. “By identifying an essential step in that signaling cascade – turning off an enzyme called SIK2 – our findings shed light on a new mechanism of PTH signaling in bone and identify a potential new treatment for osteoporosis,”

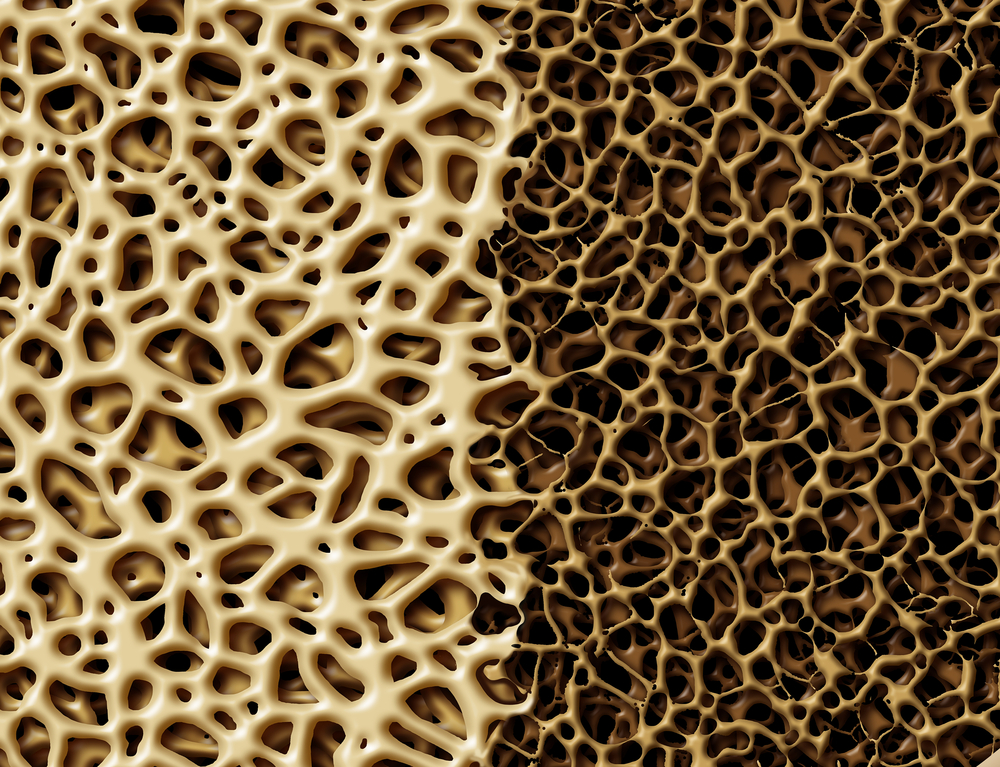

Most currently available osteoporosis drugs work by slowing down the destruction of bone, but their effectiveness is limited and long-term use can occasionally have side effects. The PTH-based drug teriparatide increases bone density; but in addition to its also accelerating bone resorption, the fact that teriparatide must be administered by daily injection discourages many patients from using it to treat a symptom-free condition. To better understand the mechanisms underlying the effects of PTH on osteocytes, the research team focused on a gene called SOST, which inhibits bone formation and is known to be suppressed by PTH.

The team’s experiments first showed that PTH suppressed SOST expression by means of transcription-regulating enzymes called HDACs – specifically HDAC4 and HDAC5 – activation of which previous research had indicated was regulated by enzymes called SIKs. In collaboration with SIK expert Olga Goransson, PhD, of Lund University in Sweden, the researchers confirmed that PTH signaling turns off the activity of the SIK2 enzyme.

A series of experiments with small-molecule SIK inhibitors – created by study co-authors Nathanael Gray, PhD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Ramnik Xavier, MD, PhD, chief of the MGH Gastrointestinal Unit – revealed that they regulated not only the expression of SOST but also of other PTH target genes such as RANKL, a molecule that stimulates bone resorption. The research team then showed that an SIK2-specific inhibitor called YKL-05-093 mimicked the effects of PTH on gene expression both in cells and in mice.

Since repeat dosing with YKL-05-093 had adverse effects on mice, the researchers tested a closely related compound YKL-05-099 and found that daily doses safely stimulated bone formation in male mice. The team was surprised to find that YKL-05-099 also reduced levels of osteoclasts – cells responsible for the breakdown of bone – indicating that it had the desired dual effect of stimulating bone formation and suppressing bone resorption.

“We don’t completely understand why YKL-05-099 reduces osteoclasts, but we think the combination could be very useful therapeutically,” says Wein, who is an instructor in Medicine at Harvard Medical School (HMS). “In addition to concentrating on understanding how this compound inhibits osteoclasts – which may lead us to develop even more specific SIK2 inhibitors – we also need to see if it increases bone mass in an animal model of postmenopausal osteoporosis, such as older female mice that have had their ovaries removed.”