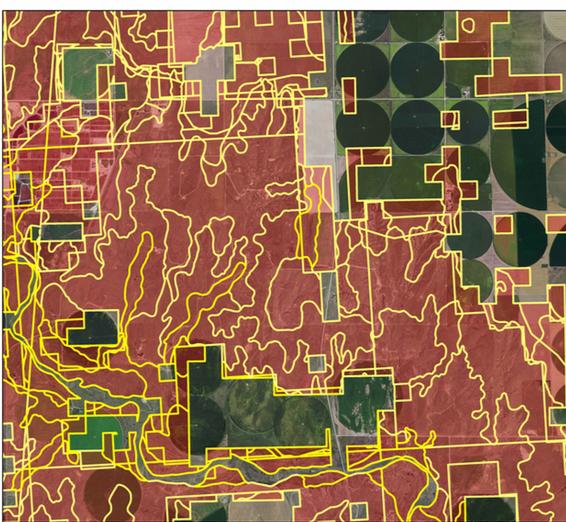

An aerial image of the research study area in southwestern Kansas. Credit: Colorado State University

Researchers from Colorado State University (CSU) have found that switchgrass–a non-edible native grass– would have a low carbon footprint if used as a biofuel.

After simulating various growing scenarios, the scientists found that switchgrass has a climate footprint ranging from -11 to 10 grams of carbon dioxide per mega-joule—the standard method to measure greenhouse gas emissions. In comparison, the impact of using gasoline results in 94 grams of carbon dioxide per mega-joule.

“What we saw with switchgrass is that you’re actually storing carbon in the soil,” John Field, a research scientist at the Natural Resource Ecology Lab at CSU, said in a statement. “You’re building up organic matter and sequestering carbon.”

The study took place at a cellulosic biofuel production plant in Kansas, one of only three in the U.S.

The team used DayCent, an ecosystem-modeling tool that tracks the carbon cycle, plant growth, and how growth responds to weather, climate and other factors at a local scale.

The tool allows scientists to predict whether crop production contributes to or helps combat climate change. It is also used to show how feasible it is to produce certain crops in a given location.

The team has focused on identifying second-generation cellulosic biofuels made from non-edible plant material like grasses that are potentially more productive as crops and can be grown with less of an environmental footprint than corn, which has emerged as a fuel source.

“They don’t require a lot of fertilizer or irrigation,” Field said. “Farmers don’t have to plow up the field every year to plant new crops and they’re good for a decade or longer.”

Previous research on cellulosic biofuels has focused on the engineering details of the supply chain. Researchers have analyzed the distance between the farms where the plant material is produced and the biofuel production plant where it must be transported.

However, in the new study, the researchers discovered that the details of where and how you grow the plant material are just as significant or possibly more significant for the greenhouse gas footprint of the biofuel.

While the biofuel industry has seen some challenges because of low oil prices and other factors, Field’s thinks the future is bright.

“Biofuels have some capabilities that other renewable energy sources like wind and solar power just don’t have,” Field said. “If and when the price of oil gets higher, we’ll see continued interest and research in biofuels, including the construction of new facilities.”

The study was published in Nature Energy.