Graphene is considered one of the most interesting and versatile materials of our time. The application possibilities inspire both research and industry. But are products containing graphene also safe for humans and the environment? A comprehensive review, developed as part of the European graphene flagship project with the participation of Empa researchers, investigated this question.

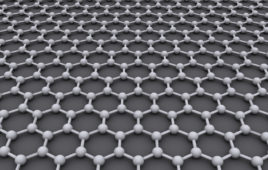

Graphene, a single layer of hexagonally arranged carbon atoms, is regarded as the miracle material of the future: it is flexible, transparent, strong, can assume different electrical properties and has the highest thermal conductivity of all known materials. This makes it extremely interesting for countless possible applications.

Europe has recognized this as well: The large-scale research program “Graphene Flagship” has been running for five years and is dedicated to this material. It is the largest research initiative that Europe has launched to date—this shows the enormous importance of graphene.

But despite all the euphoria: As with any new technology, the potential downsides have to be taken into account early on. In the past, these were often investigated too late. For example, asbestos, once appreciated for its fire retardant properties, was used in the early 20th century to manufacture numerous products—but health hazards were only gradually discovered. In 1970, asbestos fibers were officially classified as carcinogenic.

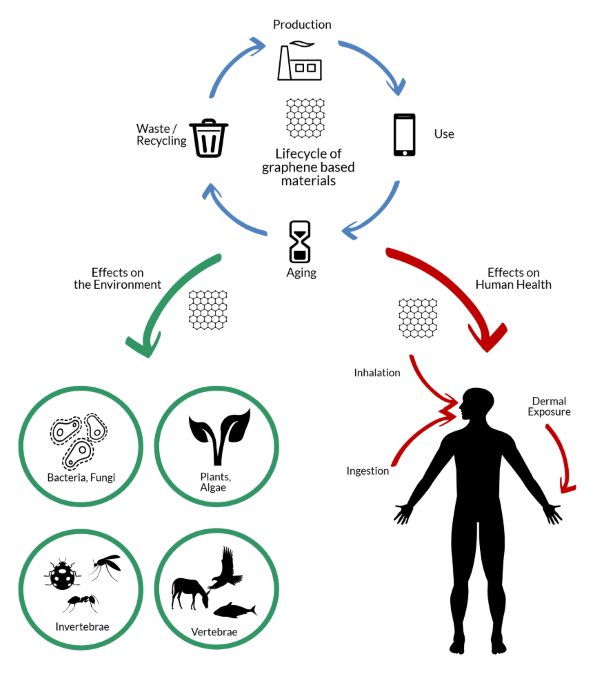

An important part of the graphene flagship is therefore dedicated to the question: Are graphene-based materials safe for humans and the environment? To this day, numerous studies have been carried out within the framework of the flagship. Empa researchers from the Particles-Biology Interactions Lab investigated for example how graphene oxide affects the human lung, gastrointestinal tract or placental barrier.

A comprehensive review article has now been published in the halfway stage of the graphene flagship project, which links the data produced within the framework of the major international research project with other published studies and thus shows the current state of knowledge on the subject of the safety of graphene-based materials. Partners from 15 European universities and research institutes participated in the review, including Empa researchers Peter Wick and Tina Bürki.

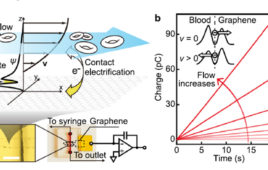

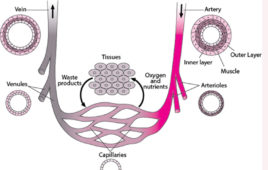

The article provides an overview of when parts of graphene-based materials can even enter the environment or the human body during their life cycle: during production, use, ageing or in the disposal or recycling process. The majority of the studies evaluated were devoted to the question of how graphene-based materials interact with the human body. These include the different ways in which materials can enter the body, for example by inhalation, ingestion or skin contact, as well as the distribution and interaction with important organs such as the central nervous system, lungs, skin, immune system, cardiovascular system, gastrointestinal tract and reproductive system.

It’s noticeable: Not all studies come to the same result. However, this is not necessarily due to the fact that the quality of individual studies is poor.

“The challenge is that not all graphene is the same,” explains Peter Wick, head of the Particles-Biology Interactions Lab at Empa.

Graphene-based materials can consist of one or more layers, the width and length of the layer can vary, and the ratio of carbon to oxygen atoms can also differ.

Depending on the combination of these three parameters, not only do completely different material properties result—the effects on humans and the environment also vary greatly. This makes simple, generally valid statements almost impossible.

“Our goal is therefore to create a detailed model for a relationship between structure and certain properties,” said Wick.

Careful characterization of the materials studied is therefore central. In the future, self-learning algorithms could help to generate a model from the data in order to predict the biological effects of a certain graphene structure.

However, such a comprehensive model is still a dream of the future.

“We see ourselves here as a kind of launch helper for determining the safety of graphene-based materials and products,” explains Wick. “Although there are more and more studies and thus indications of how graphene-based materials affect living systems, there are still gaps in our knowledge. These gaps need to be filled before we can make a clear prediction about how a graphene-based material with certain properties will affect biological systems.”

The aim is to create a new standard for authorities, research and industry so that the miracle material graphene can also be used safely.