Solutions of organic dye molecules could be easily separated by the dual-spaced membrane. Image: © 2019 KAUST; Anastasia Khrenova

The nanoscale water channels that nature has evolved to rapidly shuttle water molecules into and out of cells could inspire new materials to clean up chemical and pharmaceutical production. KAUST researchers have tailored the structure of graphene-oxide layers to mimic the hourglass shape of these biological channels, creating ultrathin membranes to rapidly separate chemical mixtures.

“In making pharmaceuticals and other chemicals, separating mixtures of organic molecules is an essential and tedious task,” says Shaofei Wang, postdoctoral researcher in Suzana Nuñes lab at KAUST.

One option to make these chemical separations faster and more efficient is through selectively permeable membranes, which feature tailored nanoscale channels that separate molecules by size.

But these membranes typically suffer from a compromise known as the permeance-rejection tradeoff. This means narrow channels may effectively separate the different-sized molecules, but they also have an unacceptably low flow of solvent through the membrane, and vice versa—they flow fast enough, but perform poorly at separation.

Nuñes, Wang and the team have taken inspiration from nature to overcome this limitation. Aquaporins have an hourglass-shaped channel: wide at each end and narrow at the hydrophobic middle section. This structure combines high solvent permeance with high selectivity. Improving on nature, the team has created channels that widen and narrow in a synthetic membrane.

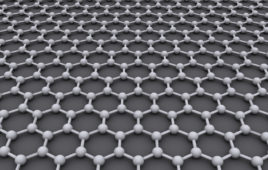

The membrane is made from flakes of a two-dimensional carbon nanomaterial called graphene oxide. The flakes are combined into sheets several layers thick with graphene oxide. Organic solvent molecules are small enough to pass through the narrow channels between the flakes to cross the membrane, but organic molecules dissolved in the solvent are too large to take the same path. The molecules can therefore be separated from the solvent.

To boost solvent flow without compromising selectivity, the team introduced spacers between the graphene-oxide layers to widen sections of the channel, mimicking the aquaporin structure. The spacers were formed by adding a silicon-based molecule into the channels that, when treated with sodium hydroxide, reacted in situ to form silicon-dioxide nanoparticles.

“The hydrophilic nanoparticles locally widen the interlayer channels to enhance the solvent permeance,” Wang explains.

When the team tested the membrane’s performance with solutions of organic dyes, they found that it rejected at least 90 percent of dye molecules above a threshold size of 1.5 nanometers. Incorporating the nanoparticles enhanced solvent permeance ten-fold, without impairing selectivity. The team also found there was enhanced membrane strength and longevity when chemical cross-links formed between the graphene-oxide sheets and the nanoparticles.

“The next step will be to formulate the nanoparticle graphene-oxide material into hollow-fiber membranes suitable for industrial applications,” Nuñes says.