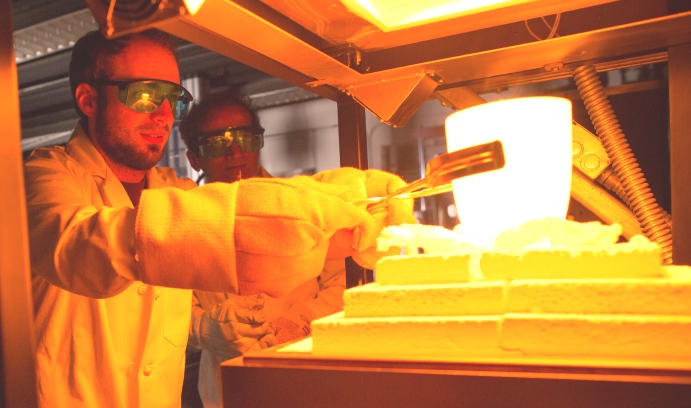

Applying a direct current field across glass, says McLaren (left, with Jain), also reduces its melting temperature and makes it possible to shape glass with greater precision than can be done using heat alone. Source: Lehigh University

Charles McLaren, a doctoral student in materials science and engineering at Lehigh University, arrived last fall for his semester of research at the University of Marburg in Germany with his language skills significantly lagging behind his scientific prowess. “It was my first trip to Germany, and I barely spoke a word of German,” he confessed.

The main purpose of McLaren’s exchange study in Marburg was to learn more about a complex process involving transformations in glass that occur under intense electrical and thermal conditions. New understanding of these mechanisms could lead the way to more energy-efficient glass manufacturing, and even glass supercapacitors that leapfrog the performance of batteries now used for electric cars and solar energy.

“This technology is relevant to companies seeking the next wave of portable, reliable energy,” said Himanshu Jain, McLaren’s advisor and the T. L. Diamond Distinguished Chair in Materials Science and Engineering at Lehigh and director of its International Materials Institute for New Functionality in Glass. “A breakthrough in the use of glass for power storage could unleash a torrent of innovation in the transportation and energy sectors, and even support efforts to curb global warming.”

As part of his doctoral research, McLaren discovered that applying a direct current field across glass reduced its melting temperature. In their experiments, they placed a block of glass between a cathode and anode, and then exerted steady pressure on the glass while gradually heating it. McLaren and Jain, together with colleagues at the University of Colorado,published their discovery in Applied Physics Letters.

The implications for the finding were intriguing. In addition to making glass formulation viable at lower temperatures and reducing energy needs, designers using electrical current in glass manufacturing would have a tool to make precise manipulations not possible with heat alone.

“You could make a mask for the glass, for example, and apply an electrical field on a micron scale,” said Jain. “This would allow you to deform the glass with high precision, and soften it in a far more selective way than you could with heat, which gets distributed throughout the glass.”

Though McLaren and Jain had isolated the phenomenon and determined how to dial up the variables for optimal results, they did not yet fully understand the mechanisms behind it. McLaren and Jain had been following the work of Dr. Bernard Roling at the University of Marburg, who had discovered some remarkable characteristics of glass using electro-thermal poling, a technique that employs both temperature manipulation and electrical current to create a charge in normally inert glass. The process imparts useful optical and even bioactive qualities to glass.

Roling invited McLaren to spend a semester at Marburg to analyze the behavior of glass under electro-thermal poling, to see if it would reveal more about the fundamental science underlying what McLaren and Jain had observed in their Lehigh lab.

A high-speed avalanche

McLaren’s work in Marburg revealed a two-step process in which a thin sliver of the glass nearest the anode, called a depletion layer, becomes much more resistant to electrical current than the rest of the glass as alkali ions in the glass migrate away. This is followed by a catastrophic change in the layer, known as dielectric breakdown, which dramatically increases its conductivity. McLaren likens the process of dielectric breakdown to a high-speed avalanche, and using spectroscopic analysis with electro-thermal poling as a way to see what is happening in slow motion.

“The results in Germany gave us a very good model for what is going on in the electric field induced softening that we did here. It told us about the start conditions for where dielectric breakdown can begin,” explained McLaren.

“Charlie’s work in Marburg has helped us see the kinetics of the process,” Jain said. “We could see it happening abruptly in our experiments here at Lehigh, but we now have a way to separate out what occurs specifically with the depletion layer.”

McLaren, Jain, Roling and his Marburg team members published their findings in the September 2016 issue of the Journal of Electrochemical Society.

“The Marburg trip was incredibly useful professionally and enlightening personally,” said McLaren. “Scientifically, it’s always good to see your work from another vantage point, and see how other research groups interpret data or perform experiments. The group in Marburg was extremely hardworking, which I loved, and they were very supportive of each other. If someone submitted a paper, the whole group would have a barbecue to celebrate, and they always gave each other feedback on their work. Sometimes it was brutally honest–they didn’t hold back–but they were things you needed to hear.”

“Working in Marburg also showed me how to interact with a completely different group of people,” he continued, “and you see differences in your own culture best when you have the chance to see other cultures close up. It’s always a fresh perspective.”