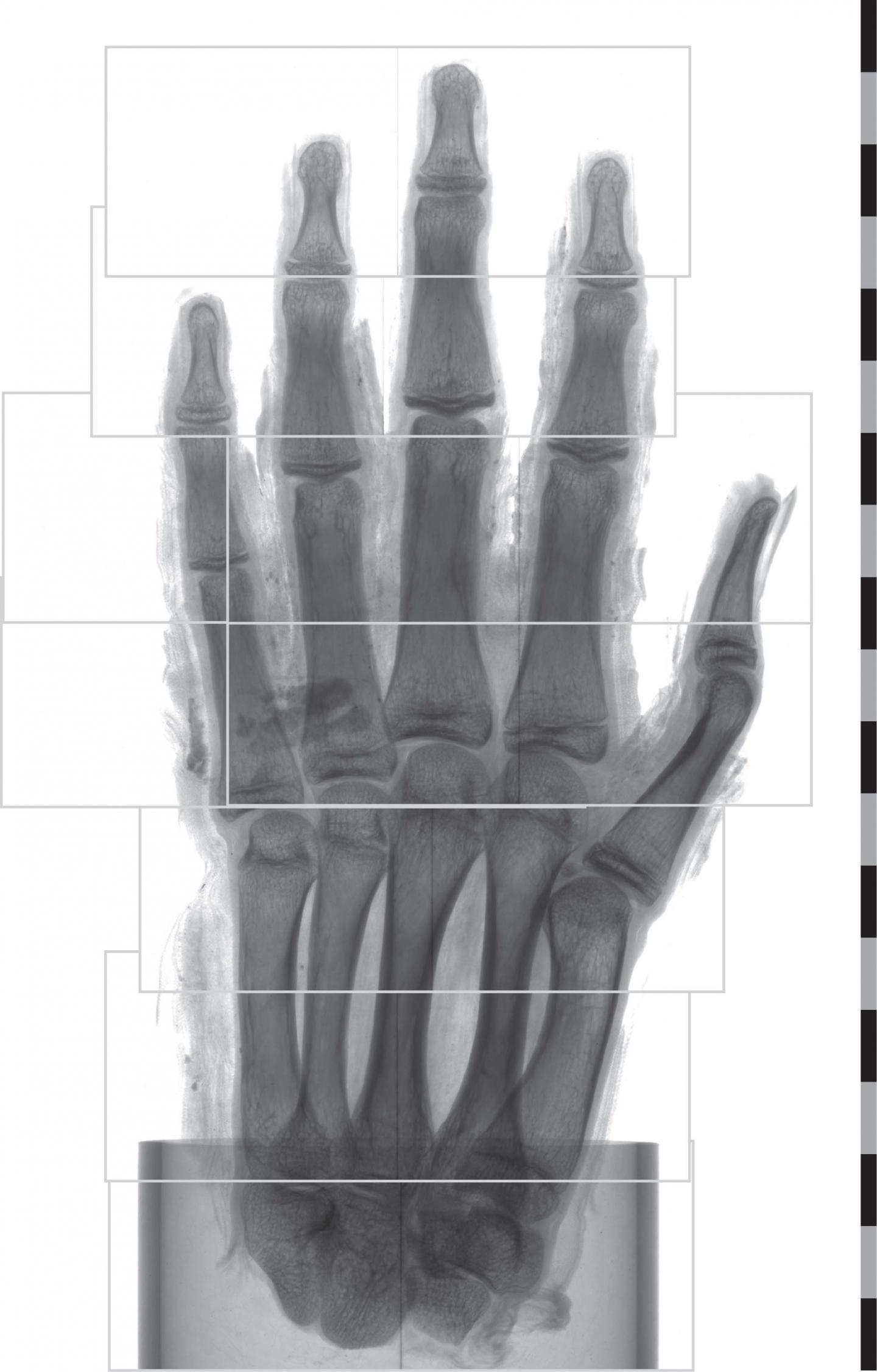

Regions for tomographic scans. For the imaging of the hand, a total of nine tomographic scans were performed. Here, the field of view for each scan is shown. Before tomographic reconstruction, the left regions of the fourth and fifth scan from the bottom were stitched together with their respective right counterpart. The scale shows centimeters. Credit: Radiological Society of North America

A team of researchers from Sweden has successfully imaged the soft tissue of an ancient Egyptian mummy’s hand down to the microscopic level using a new computer tomography (CT) scan.

In the past, archaeologists and paleopathologists have used non-destructive imaging techniques like X-rays and CT scans for human and animal mummies to gain a better understanding of life and death in ancient times and improve the understanding of modern diseases.

Both imaging techniques predominately take advantage of the fact that materials absorb different amounts of X-rays—a phenomenon called absorption contrast that creates different degrees of contrast within an image.

“For studying bone and other hard, dense materials, absorption contrast works well, but for soft tissues the absorption contrast is too low to provide detailed information,” Jenny Romell, from KTH Royal Institute of Technology and Albanova University Center in Stockholm, said in a statement. “This is why we instead propose propagation-based phase-contrast imaging.”

Propagation-based imaging enhances the contrast of X-ray images by detecting both the absorption and phase shift that occurs as X-rays pass through a sample, similar to how a ray of light changes direction as it passes through a lens. By capturing both the absorption and phase shift, a method they dubbed phase-contrast CT, the researchers can obtain a higher contrast for soft tissues.

“There is a risk of missing traces of diseases only preserved within the soft tissue if only absorption-contrast imaging is used,” Romell said. “With phase-contrast imaging, however, the soft tissue structures can be imaged down to cellular resolution, which opens up the opportunity for detailed analysis of the soft tissues.”

The researchers imaged a mummified human right hand that belonged to an Egyptian man from around 400 BCE (before common era) to test the phase-contrast CT. The hand is currently in the collection of the Museum of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Antiquities, after being brought to Sweden at the end of the 19th century with other mummified body parts and a fragment of mummy cartonnage.

The researchers scanned the entire hand and performed a more in-depth scan of the tip of the middle finger with an estimated resolution between six and nine micrometers—slightly more than the width of a human red blood cell.

This enabled the researchers to see the remains of adipose cells, blood vessels and nerves. The researchers were even able to identify blood vessels in the nail bed and differentiate the different layers of the skin.

“With phase-contrast CT, ancient soft tissues can be imaged in a way that we have never seen before,” Romell said.

The insight could allow phase-contrast CT as an alternative or in conjunction with more invasive methods used in soft-tissue paleopathology that require the extraction and chemical processing of the tissue.

“Just as conventional CT has become a standard procedure in the investigation of mummies and other ancient remains, we see phase-contrast CT as a natural complement to the existing methods,” Romell said. “We hope that phase-contrast CT will find its way to the medical researchers and archaeologists who have long struggled to retrieve information from soft tissues, and that a widespread use of the phase-contrast method will lead to new discoveries in the field of paleopathology.”

The study was published in Radiology.