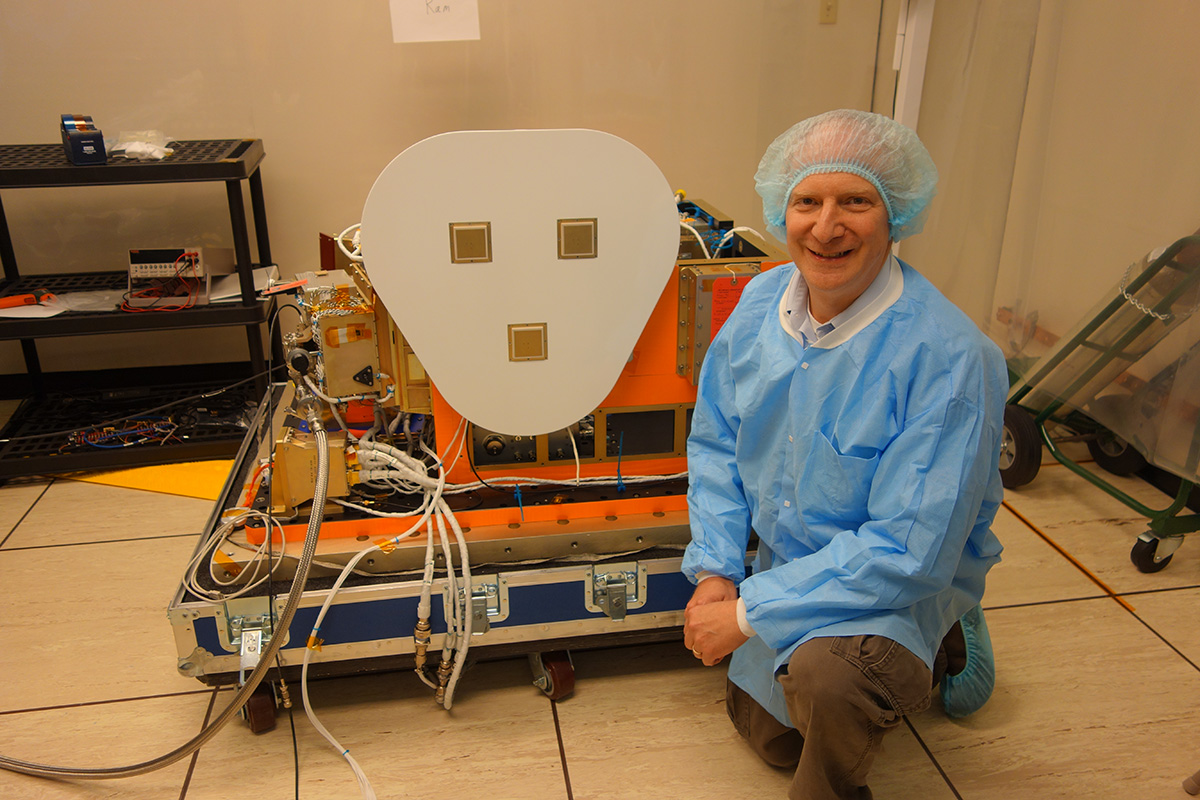

Steven Powell, research engineer in the department of electrical and computer engineering, is pictured with the Cornell GPS antenna array in a cleanroom at the NASA/Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. The array is currently mounted on the truss structure of the International Space Station. Image: Zach Tejral, NASA Johnson Spaceflight Center/Provided

The weather here on Earth has been a little strange this winter — 60-degree days, followed by blinding snow, only to be followed by 50s and rain — but for Steven Powell, the weather he’s interested in can’t be felt by humans or measured by barometric pressure.

Powell, research support specialist in electrical and computer engineering, is concerned with “space weather” — charged particles in the plasma of space, on the edge of the Earth’s atmosphere. These particles affect the performance of communications and navigation satellites.

To study conditions in the ionosphere, a band between 50 and 600 miles above the Earth, Powell and others in the College of Engineering have developed the FOTON (Fast Orbital TEC for Orbit and Navigation) GPS receiver, which was built in a Rhodes Hall lab. Last month, the FOTON hitched a ride aboard the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket to begin a long-term project at the International Space Station.

The project, which could last two years, is called GROUP-C (GPS Radio Occultation and Ultraviolet Photometry-Colocated), and is headed by Scott Budzien of the Naval Research Laboratory. Powell is the Cornell principal investigator for the project; other Cornell contributors include Mark L. Psiaki, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering (retired); David Hysell, professor of earth and atmospheric sciences; Todd Humphreys, Ph.D., and Brady O’Hanlon, Ph.D.

Also contributing was the late electrical and computer engineering professor Paul Kintner, who died in November 2010. Kintner was responsible for the original ionospheric research that formed the scientific basis for GROUP-C, Powell says.

The STP-H5 palette of instruments being maneuvered by the robotic arm on the International Space Station. The Cornell antenna array is visible just to the right of the “Canada” logo. This photo was taken during the installation process. NASA Johnson Spaceflight Center/Provided

The FOTON is a highly sensitive GPS receiver, designed to withstand the rigors of spaceflight while detecting subtle fluctuations in the signals from GPS satellites.

“These fluctuations help us learn about the ionosphere in which the signals travel,” says Powell, who returned to Ithaca in early March after spending six weeks in Alaska on a project to send two sounding rockets into the aurora borealis, also to study the ionosphere.

“These fluctuations are typically filtered out by standard GPS receivers,” he says, “but they are the scientific ‘gold nuggets’ in the data analysis process.”

Powell’s experiment is one of a number of projects studying the Earth’s atmosphere and ionosphere. It shares a mounting palette on the outside of the ISS, receives power from large solar arrays, and uses the data communications system onboard the station to quickly distribute data back to Earth.

Powell and Hysell will collect data from the GROUP-C experiment.

GROUP-C’s position onboard the ISS will allow it to study the ionosphere “at an edge-on perspective,” Powell said, to measure variations in electron density. The Cornell team’s GPS receiver and antenna — actually a suite of three antennas, configured to maximize GPS signals and minimize unwanted reflections from the large metal portions of the ISS — will focus on GPS satellites as they move across the sky and set behind the Earth.

As they set, Powell says, the radio signals travel through the ionosphere and are subtly delayed by the denser regions of the ionosphere. “From that, we obtain a vertical profile of the electron density,” he says.

This experiment builds on a short-duration NASA sounding-rocket mission Powell led in 2012, which was sent into the aurora to study the ionosphere at high latitudes, near the North Pole.

“This experiment will allow us to study different, but equally interesting, effects in the ionosphere closer to the equator, where most of the world’s population lives,” Powell says.

The Feb. 19 liftoff of the SpaceX rocket, and docking with the ISS four days later, was the culmination of a nearly four-year effort to get GROUP-C built.

“It was extremely exciting and satisfying to see the GROUP-C experiment [launch],” Powell says. “I’ve been involved in more than 50 space-based research efforts over a 30-year period, but most have been using suborbital NASA sounding rockets, with mission durations of just 10 to 30 minutes.

“The GROUP-C experiment duration will last up to two years,” he says, “so the quantity of data and the potential for meaningful scientific discovery is huge.”

Source: Cornell University