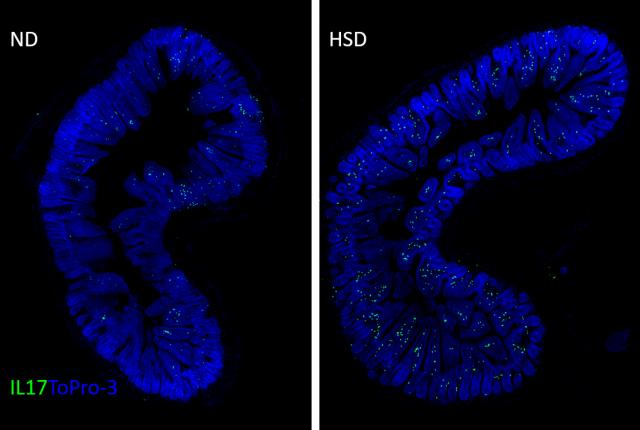

White blood cells that produce a protein called IL-17 (green) accumulate in large numbers in the small intestine of mice fed a high-salt diet for eight weeks (right), compared with mice fed a normal diet. This magnified image shows cells in a part of the intestinal layer that absorbs digested food and protects against infection. Credit: The Iadecola Lab

Salt-laden foods may be increasing your risk of dementia, according to a new study.

Scientists from the Weill Cornell Medicine have found that a high-salt diet reduces the resting blood flow to the brain and causes dementia in mice, the first study linking dietary salt intake to neurovascular and cognitive impairment.

The study could result in a potential target for countering harmful effects to the brain caused by excess salt consumption.

“We discovered that mice fed a high-salt diet developed dementia even when blood pressure did not rise,” senior author Dr. Costantino Iadecola, director of the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute (BMRI) and the Anne Parrish Titzell Professor of Neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine, said in a statement. “This was surprising since, in humans, the deleterious effects of salt on cognition were attributed to hypertension.”

In the study, the mice were given food containing either 4 percent or 8 percent salt, representing an eight-to-16 fold increase in salt compared to a normal mouse diet. The scientists examined the mice using magnetic resonance imaging after eight weeks and found a decrease of 28 percent in resting cerebral blood flow in the cortex and a 25 percent decrease in the hippocampus, the two areas of the brain involved in learning and memory.

They also found an impaired ability of cells lining blood vessels, called endothelial cells, reduced the production of nitric oxide—a gas produced by the endothelial cells to relax blood vessels and increase blood flow.

The researchers returned some of the mice to a regular diet for four weeks to see if the biological effects of a high-salt diet could be reversed. These mice had their cerebral blood flow and endothelial function return to normal.

Rodents that only ate the high-salt diet developed dementia, performing significantly worse on an object recognition test, a maze test and nest building–a typical activity of daily living for mice, spending less time building nests and using much less nesting material than normal mice.

The team then performed several experiments to understand the biological mechanisms connecting high salt intake with dementia and found that the mice developed an adaptive immune response in their guts, with increased activity of a subset of white blood cells that play a crucial role in the activity of other immune cells.

The increase in the white blood cells, T helper lymphocytes called TH17, boosted the production of a protein called interleukin 17 (IL-17) that regulates immune and inflammatory responses, causing a reduction in the production of nitric oxide in endothelial cells.

To conclude the study, the researchers treated the mice with ROCK inhibitor Y27632, a drug known to prevent the suppression of nitric oxide activity.

The drug reduced circulating levels of IL-17 and the mice showed improved behavioral and cognitive functions.

“The IL-17-ROCK pathway is an exciting target for future research in the causes of cognitive impairment,” Dr. Giuseppe Faraco, Ph.D., an assistant professor of research in neuroscience in the BMRI and first author of the study, said in a statement. “It appears to counteract the cerebrovascular and cognitive effects of a high-salt diet, and it also may benefit people with diseases and conditions associated with elevated IL-17 levels, such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and other autoimmune diseases.”

According to the researchers, about 90 percent of American adults consume more than 2,300 mg of sodium per day, surpassing the recommended amount.

The study was published in Nature Neuroscience.