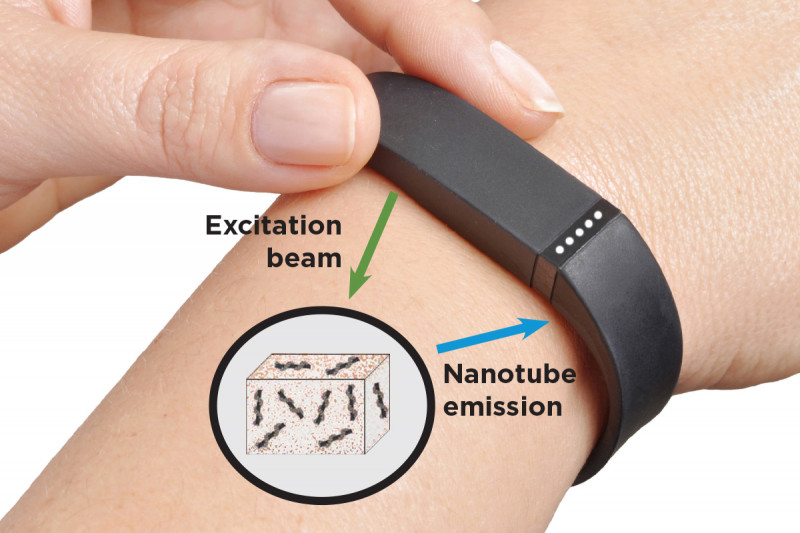

Researchers envision a new way of monitoring cancer and other diseases by implanting nanotube sensors under the skin. A small device worn on the wrist could send light into the sensors (excitation beams) and analyze the light coming back out (nanotube emission) to provide constant updates.

A major challenge in diagnosing and treating cancer is knowing exactly what’s going on inside the body without conducting invasive or time-consuming procedures. Is a drug actually slowing tumor growth? Has the cancer started developing resistance to therapy?

Memorial Sloan Kettering researchers are hoping they can address this problem with tiny implantable sensors made up of needlelike carbon nanotubes that can easily be placed in tissues. The nanotubes that make up the sensors are so small that millions of them could fit on the head of a pin.

The sensors work by absorbing and emitting harmless infrared light that provides information on disease biomarkers, which are molecules that indicate biological activity — such as whether a tumor is growing or not. The light can travel through several centimeters of tissue and still be readily detected and analyzed.

This means the nanotube sensors could be implanted under the skin, and a small device worn on the wrist could send light into them and analyze the light coming back out — acting as a kind of fitness tracker for disease.

“We wanted to find a way to noninvasively measure biomarkers that are still in the body,” MSK molecular pharmacologist Daniel Heller says. “This work would be a major step forward compared with standard biopsies, which can’t be repeated every day, and certainly not every minute.”

The new technique is reported in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering by Dr. Heller, first author Jackson Harvey (a graduate student in Dr. Heller’s lab), and other colleagues from MSK, Lehigh University, and the University of Rhode Island.

The nanotube sensors keep tabs on microRNAs (miRNAs), which are small RNA molecules that can function as biomarkers for certain cancers or other diseases. Some of these miRNAs circulate in the blood, but the sensor also could be implanted to detect biomarkers in tissues without a readily available blood supply.

Shining infrared light onto the nanotubes and analyzing the signal that comes back may reveal valuable information about disease activity at that part of the body. The sensors could detect cancer in people at high risk, or in patients who have been successfully treated but have a strong chance of recurrence. In those who are undergoing treatment, the sensors could immediately report whether a biomarker is going up or down and — when needed — help a doctor know to switch from one drug to a second-line therapy.

“A lot of these microRNAs we’re looking at seem to be potential indicators of diseases, mostly cancers, that don’t currently have good early biomarkers,” Heller explains. “The best ones need to be identified and validated so we know which ones to focus on as we take this technology forward.”

For tumors deep in the body, the information could be gleaned through alternative means. “You might be able to implant it in the digestive tract near a tumor or precancerous lesion and get a readout by using an endoscope to shine and analyze the light,” Heller says. “You could even use this in the skull because the light has no problem passing through bone.”

In the Nature Biomedical Engineering study, the researchers showed in test tubes that the sensor detected changes in the concentration of a variety of miRNAs. “We’ve also shown that we can make different colors of nanosensors that are specific for different microRNAs,” Harvey says. “So we could have nanotubes sensing multiple microRNAs, which could give us an entire disease ‘fingerprint.’”

They also implanted the sensors in mice, within a small porous “pouch” that trapped the sensors but let miRNAs flow in and out.

It’s not yet clear which miRNAs will be the best to test for in a given disease, although other researchers at MSK and elsewhere are narrowing down the candidates. While other labs untangle biomarker biology, Heller’s team will continue to work the problem from the technology end, refining the sensor approach to be even more reliable at measurement.

“Right now, it’s hard to tell if a patient has an aggressive cancer, or if it’s safe to wait a while before another scan — do you tell them to come back tomorrow or in three months?” Heller says. “If you could see a change in biomarker levels in hours or days, it could give physicians an earlier warning.”

“This may sound like science fiction, but we’re working to make it reality,” he adds.