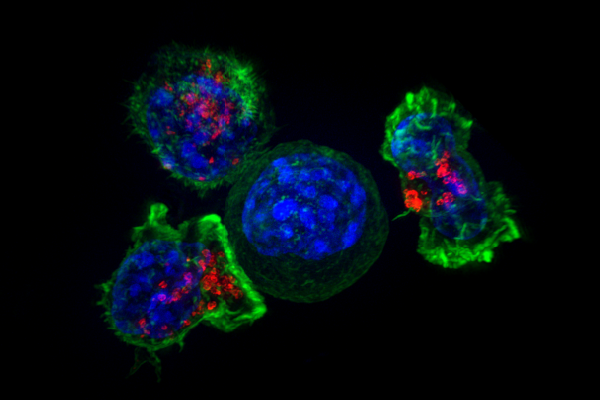

Killer T cells surround a cancer cell. Credit: NIH

A newly engineered antibody holds promise in leading the fight against cancerous tumors.

Researchers from the University of Southampton have developed a new antibody that could unlock cancer’s defense against the body’s immune system by targeting 4-1BB, an immune receptor that can activate the killer T-cells to find and destroy cancer cells.

The researchers found that 4-1BB is present mainly on a population of T cells within regulatory T cells, which switch off the killer T cells.

The team found that in a pre-clinical tumor, setting an anti-4-1BB antibody that deleted regulatory T cells caused regression in the tumor. However, because the type of antibody that is good at deleting regulatory T-cells does not stimulate the killer T-cells and vice versa, it is not possible to use a regular type of antibody to harness both therapeutic approaches.

In the study, the researchers designed and engineered the new antibody to delete the regulatory T cells within the cancerous tumor, removing the suppression they exert, while also activating the killer T cells at the same time. In laboratory testing, the dual-purpose antibody was highly effective in eradicating cancerous tumors.

“Antibody immunotherapy has transformed patient outcomes in a number of cancers, but responses are frequently restricted to a minority of patients,” professor Stephen Beers said in a statement. “This is really very exciting breakthrough.

“Immune activating antibodies targeting immune receptors like 4-1BB have failed to translate successfully to the clinic but hold great potential if we can understand how to target them successfully in cancer patients,” he added. “We have identified some of the reasons that stop them treating cancer and for the first time, demonstrated that you can combine the two approaches of deleting regulatory T cells and activating killer T cells. This could potentially improve the way we treat patients in the clinic.”

The researchers believe the antibody can be applied to both ovarian cancer and a common form of non-melanoma skin cancer called Squamous Cell Carcinoma. However, the research team thinks it could be applicable to more cancers with further research.

“This study is an important step towards improving immunotherapy,” Sean Lim, PhD, Cancer Research UK’s expert in immunotherapy, said in a statement. “It helps us to understand why this type of treatment isn’t as successful in patients as hoped.

“But critically, it also presents a potential solution as to how we can overcome these challenges to develop effective immunotherapy that works for more patients,” he added.

The study was published in Immunity.