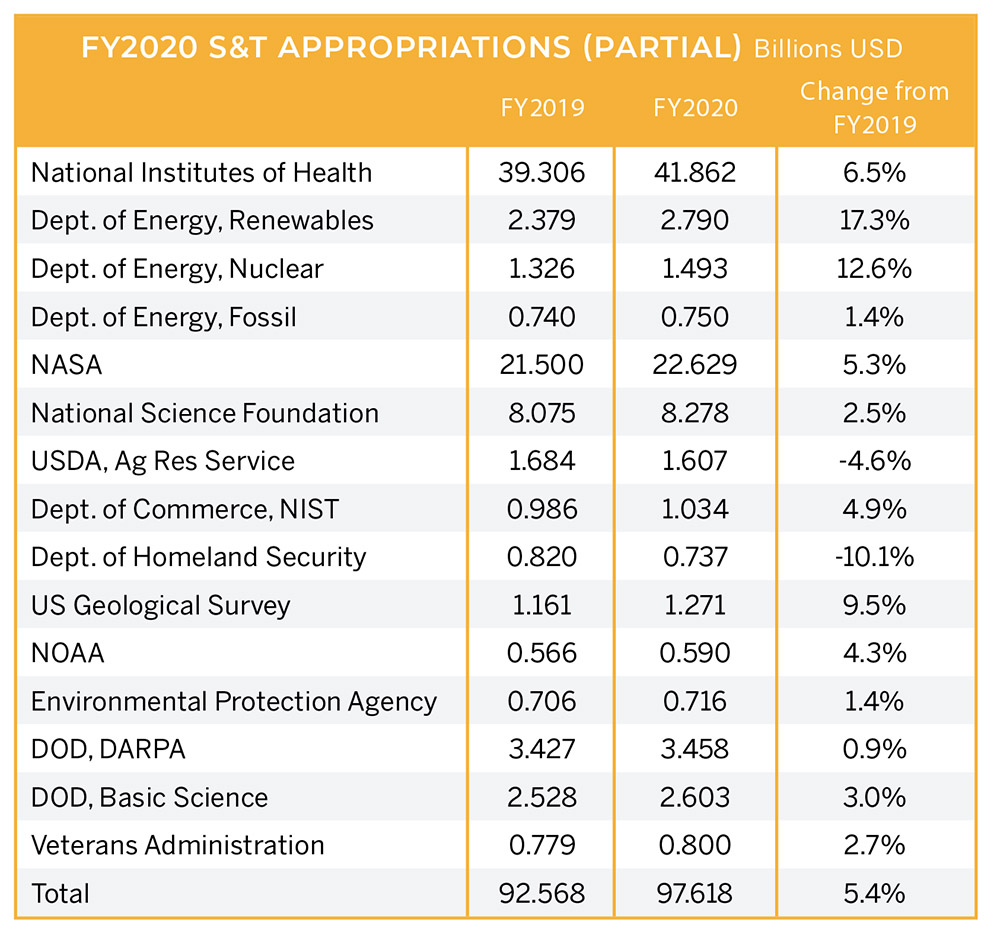

Facing a Federal government shutdown deadline at midnight on Dec. 20th, a Presidential impeachment vote (on Dec. 18th) with a highly polarized Congress, the U.S. Congress, Senate and Administration voted on and signed into law (just hours before the Dec. 20th shutdown deadline) its final appropriations package for FY2020. The package included the Consolidated Appropriations Act and the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).

The signed $1.4 trillion FY2020 omnibus spending bills extend the possibility of a government shutdown to the end of FY2020 on September 30, 2020. The bills include substantial budget increases for several government agencies. These are comparable to the increases in Federal spending caps the Congress agreed to in the summer of 2019 with some science agencies now seeing even larger increases than were seen last summer.

New opportunities for defense R&D

The DOD’s S&T budget is the largest research, development, test and evaluation budget in 70 years, according to David Norquist, the DOD’s deputy defense secretary. And while the Congress reduced the overall DOD budget request, it increased R&D funding.

The signed NDAA includes the creation of a Space Force, a Climate Security Advisory Council and directs the Dept. of Defense’s research security efforts. The research security funding provides for both the collection of information relating to U.S. citizens and foreign national in the U.S. who participate in defense R&D activities, and for maintaining the privacy of that information. It explains how the DOD should collaborate with academia to disseminate best practices on this data collection. It also directs researchers to collect and maintain lists of academic institutions in Russia, China and other countries that seem to pose research security risks.

Another NDAA program establishes processes to ensure the DOD continuously updates policies relating to emerging technologies, including how they might bear on treaties. Examples of these emerging technologies include quantum computing, big data analytics, artificial intelligence, autonomous technologies, robotics, directed energy, hypersonics, and biotechnology.

The creation of a Space Force is relatively modest budget item from an R&D standpoint and primarily takes over activities carried out currently by the U.S. Air Force’s Space Command. Space Force R&D will primarily focus on a small portfolio of high-priority technology development projects for the DOD’s Space Development Agency (SDA). Other NDAA R&D will focus on development of a space-based missile defense, earth-observing satellites, support for a joint hypersonic transition office, development of low-yield nuclear weapons warheads, production of plutonium weapons cores, production of low enriched uranium for naval reactors, and the reestablishment of a commission to assess the threats from electromagnetic pulses (EMPs) produced during nuclear detonations.

Continued recovery for NIH

In their FY2020 R&D budget, every one of the 27 National Institutes of Health (NIH) institutes and centers received at least a 3.3% increase above their FY2019 funding, and some received a lot more. The administration’s actual FY2020 proposal for the NIH was 12% less than actual FY2019 spending, but wound up being about 7% more at $41.684 billion. The strong NIH funding increase continued its recovery from sequestration-level funding in FY2013 and the basically flat funding for the previous decade. The National Institute on Aging led the way in the NIH’s FY2020 funding with a 14.9% increase with research on Alzheimer’s research (again) prioritized. Funding of NIH facilities more than doubled over FY2019 funding to $425 million. The Congress also provided $500 million for opioid-related research, split between the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) received a $600 million increase over its FY2019 spending. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) got a 5% increase to $6.440 billion. The National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering received 4% budget increase to $404 million.

Mixed energy bag

In their initial budget proposal, the administration cut 16% in the Dept. of Energy’s Office of Science (OS) FY2020 budget from its $6.585 billion FY2019 budget. The final FY2020 approved and signed budget for the OS was $7.000 billion — a 6% actual increase over the OS’s FY2019 R&D spending. Actually, it was proposed that six of the OS component R&D budgets be reduced from their FY2019 levels by 2% to 30%. And each of the six had their budgets increased by 2% to 19% (i.e., Advanced Scientific Computing, +5%; Basic Energy Sciences, +2%; Fusion Energy Sciences, +19%; High Energy Physics, +7%; Nuclear Physics, +3%; and Biological and Environmental Research, +6%). Included in the fusion energy programs, the ITER (initially the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) being built in Southern France had its $132 million FY2019 budget nearly doubled to $242 million, but at the expense of other fusion research, which was cut by 4%. DOE-supported earth system science projects were protected from large administration-backed budget cuts, while nuclear physics research and operations were given a 7.3% R&D budget increase.

Renewable energy programs within the DOE were also endorsed by the House and Senate legislators with a 13% increase for wind-based research and a 41% increase for water power research. Automotive battery and electrification R&D increased in the DOE budget by 7%, while photovoltaic (solar cells) R&D increased by 6% over FY2019 levels.

To the moon and beyond

The final FY2020 R&D budget for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration is close to the proposed budget initially submitted — $22.6 billion, or 5% more than its FY2019 budget. Many NASA line items are supported but funding for development of a lunar landing vehicle was only funded to $744 million, while the agency requested $1 billion for development of an Artemis landing system, which is targeted for a 2024 launch/lunar landing date.

Budget wording for Artemis was also specific in making the lander flexible enough to be launched on any U.S. launch vehicle, commercial or otherwise, that is available for a lunar exploration mission — since no single vehicle is currently verified to satisfy the landing requirements. NASA’s Europa Clipper and lander program, designed to study Jupiter’s icy moon Europa in 2025-2026 or so, was also reduced from its FY2019 funding level by about 20% to $593 million.

Other agencies

The National Science Foundation also saw an overall increase in funding from $8.1 billion in FY2019 to $8.3 billion in FY2020, a 3% rise. Of that increase, research and related activities accounted for slightly more than 81% — $6.737 billion, a 3.33% increase over similar funding in the FY2019 R&D budget.

The National Oceanographic & Atmospheric Agency was one of the few science agencies to see a cut in its overall FY2020 R&D budget, to $5.352 billion from FY2019’s $5.425 billion — a 1.34% reduction. The biggest part of this cut came from NOAA’s National Environmental Satellite, Data & Information Service which went from $1.7 billion funding in FY2019 to $1.514 billion in FY2020, a 10.9% reduction. Most other NOAA components actually saw budget increases in FY2020 from +0.5% to +13.1%.

The Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology was another S/E agency to see a funding increase in FY2020 from $0.986 billion in FY2019 to $1.034 billion in FY2020 — a 5% increase. This funding was split between Scientific and Technical Research and Services, $0.754 billion (4% increase from FY2019), Industrial Technology Services, $0.162 billion (5% increase from FY2019) and Construction of Research Facilities, $0.118 billion (1% increase from FY2019).

Foreign threats to U.S. research

For years, there have been claims of foreign threats to U.S. research, from outright theft of government secrets to enticements of high-level researchers and plagiarism of product designs and concepts. Congress has created two panels to address these concerns as they apply to foreign researchers working or studying in the U.S. One of these panels is headed by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). This panel is expected to collect actions from multiple government agencies to protect federally funded research from cyber attacks, theft, and other foreign threats. The other panel will be a roundtable by the National Academy of Sciences on how to assess and mitigate potential threats from collaborations between foreign and U.S. researchers.

A recent NAS panel cited the challenges posed by China’s efforts to build its industries around emerging technologies through its “Made in China 2025 Plan.” Mike Molnar, who leads NIST’s Office of Advanced Manufacturing, stated in the panel that China is on track to meet its goal of establishing 40 manufacturing innovation institutes by 2025, which are the basis for building up new industrial clusters. To support these new R&D centers, China has consistently been aggressively recruiting innovation talent throughout the U.S. by traveling to multiple universities hoping to entice researchers to move to China.

A recent report requested by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and prepared by the MITRE Corp.’s Jason program, Fundamental Research Security – Dec. 2019, addresses research integrity in the U.S. and foreign influences on it. This report examined 1) the value and need for foreign scientific talent in the U.S.; 2) the impacts of placing restrictions on access to U.S. research; 3) the need to define research integrity to include disclosures of commitments and conflicts of interest and 4) the creation of a common understanding within research organizations on how to protect U.S. research interests, while continuing to compete globally.

The Jason report found that problems of foreign influence can be addressed within a revised framework of research integrity. The benefits of research openness and the inclusion of foreign researchers outweigh measures of limiting access to fundamental research for security purposes. The report criticized U.S. intelligence agencies for assuming research theft in cases that actually appear to be the foreign researcher’s collegial sharing of their academic work. The report authors further state that a reinvigorated commitment to U.S. standards of research integrity and the tradition of open science by all stakeholders will continue to drive U.S. preeminence in science, engineering and technology by attracting and retaining the world’s best talent.

This article is part of R&D World’s annual Global Funding Forecast (Executive Edition). This report has be published annually for more than six decades. To purchase the full, comprehensive report, which is 58 pages in length, please visit the 2020 Global Funding Forecast homepage.

Tell Us What You Think!