The COVID-19 pandemic created numerous issues in early 2020 relating to academic R&D. When the pandemic first spread throughout the U.S. in March, schools were among the first establishments to close their facilities to prevent the spread of the virus. This remained the standard operating mode through the end of the year.

With no students, universities saw a drastic reduction in revenue and shortfalls in operating funds. This drop was a big blow to many universities that had already been struggling financially. Externally funded R&D, in general, was not as severely affected. This was especially true of federally funded programs, which only saw minor temporary funding bumps. But the infrastructure became at risk. And student support for research programs became troubling at best.

By the end of the year, with both remote learning in place and the prospect of successful vaccines, many of these issues were somewhat under control. More troubling was the change in research focus toward COVID vaccines at the expense of research on other life science programs.

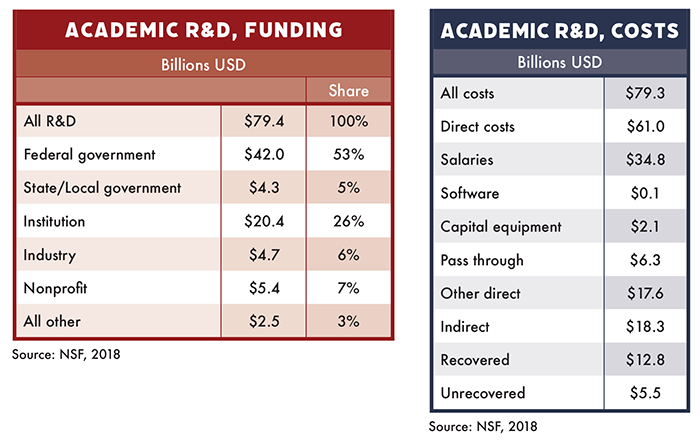

Little research has been done on the effects of this transfer of resources, which will likely be slightly alleviated in 2021, especially as new funding supplements become available targeted directly at COVID-based concerns. Also, in many large urban communities, university hospitals — which had been strong research-based facilities — became overloaded with COVID-infected patients, testing procedures and increased cleaning and security protocols. Research programs at those facilities have been delayed, to say the least. As noted in the nearby chart, about 60% of the R&D performed (by dollar amounts) in academia is life-science based. So when that level of R&D is suddenly refocused on solving massive pandemic-related issues, the overall focus of university R&D is at risk.

Little research has been done on the effects of this transfer of resources, which will likely be slightly alleviated in 2021, especially as new funding supplements become available targeted directly at COVID-based concerns. Also, in many large urban communities, university hospitals — which had been strong research-based facilities — became overloaded with COVID-infected patients, testing procedures and increased cleaning and security protocols. Research programs at those facilities have been delayed, to say the least. As noted in the nearby chart, about 60% of the R&D performed (by dollar amounts) in academia is life-science based. So when that level of R&D is suddenly refocused on solving massive pandemic-related issues, the overall focus of university R&D is at risk.

The whole pandemic experience has dramatically changed the way academic R&D is and will be performed in the future. The risks, the urgency and the personal sacrifices (and the obvious costs) far exceeded what had been seen in previous life science R&D programs. And it is far from over.

Academia still has an enormous amount of work to do in bringing their facilities and operations back to some level of normalcy. There’s also a vast amount of research necessary to specifically determine why the large differences in the case loads occurred between countries and what can be done when the next deadly virus appears. The U.S. did not handle this specific COVID-19 virus well despite several decades of experience in identifying an annual influx of influenza invasions. The next COVID-19 variant could be much more deadly. Hopefully, researchers will have learned something from this iteration — clearly the general public does not seem to have learned much from it.

Academia still has an enormous amount of work to do in bringing their facilities and operations back to some level of normalcy. There’s also a vast amount of research necessary to specifically determine why the large differences in the case loads occurred between countries and what can be done when the next deadly virus appears. The U.S. did not handle this specific COVID-19 virus well despite several decades of experience in identifying an annual influx of influenza invasions. The next COVID-19 variant could be much more deadly. Hopefully, researchers will have learned something from this iteration — clearly the general public does not seem to have learned much from it.

Changes

In the past, academic R&D, especially in the life science arena, was mostly secretive. There was collaboration only among financially secure partners, and testing results were held close to the vest to insure strong financial rewards upon successful completion (or to minimize the financial penalties upon publication of testing failures). During the COVID-19 vaccine development, researchers freely exchanged information and data. The result was the identification, development, testing, full-scale clinical trial qualification, production and global distribution of basically billions of doses of the vaccine — all in less than a year. This scale of drug development often takes between six to 10 years to accomplish.

It is clearly doubtful that this level of collaboration and communication will carry over into the development of other less pervasive healthcare products. Its possible that some collaborations will be maintained into the future, but only following approval from the various legal departments of the involved parties.

Assuming vaccines currently being distributed continue to meet expectations, and the pandemic slowly withers away over 2021 with no major unexpected re-surgences, academic research labs will return to some semblance of normalcy by mid-2021. COVID cases will likely remain with us, primarily due to those anti-vaxers who refuse to be inoculated. As a result, full-scale ramp-up of R&D programs to the levels seen before 2020 won’t likely occur until 2022. And even then, strong security and social distancing measures will probably remain in place.

Principal researchers and grad student assistants could resume their pre-COVID levels of R&D by late-2021, again with full levels of security and social distancing still in place.

It is unlikely that academia will return to its normal level of person-to-person instruction before early 2022. And even then, academic administrations will have to make some accommodations to ensure their tuition-paying ‘customers’ are safe and comfortable.

The data presented in this section concerning the various dollar amounts of R&D performed in 2018, following several years of strong growth are likely to be closely matched in 2022, with some growth beyond that level occurring in 2023.

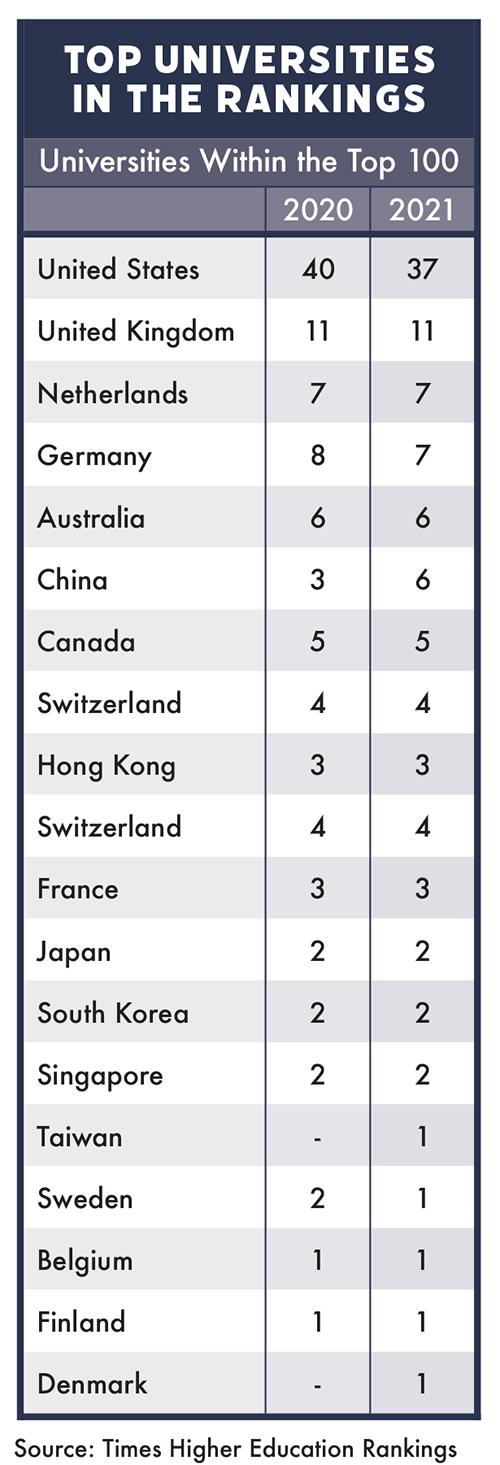

The good news: The strength of the U.S. academic community is likely to return by 2022. Other countries, especially in Asia, will make inroads into that strength, but the overall strength of U.S. academia should prevail despite the operational “blip” in 2020. U.S. academia still had Nobel prize winners in chemistry, physics and economics in 2020 — and that expertise remains in place without any hindrances. China will continue to boost its academic R&D infrastructure in 2021 and beyond and could approach the level of U.S. and European acceptance by 2030.

This article is part of R&D World’s annual Global Funding Forecast (Executive Edition). This report has been published annually for more than six decades. The Executive Edition will be published in the April 2021 print issue of R&D World. To purchase the full, comprehensive report, which is 54 pages in length, please visit the 2021 Global Funding Forecast homepage.

Tell Us What You Think!