Researchers are building spider-inspired sensors into the shells of autonomous drones and cars so that they can detect objects better. Image: Taylor Callery

What if drones and self-driving cars had the tingling “spidey senses” of Spider-Man?

They might actually detect and avoid objects better, says Andres Arrieta, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Purdue University, because they would process sensory information faster.

Better sensing capabilities would make it possible for drones to navigate in dangerous environments and for cars to prevent accidents caused by human error. Current state-of-the-art sensor technology doesn’t process data fast enough—but nature does.

And researchers wouldn’t have to create a radioactive spider to give autonomous machines superhero sensing abilities.

Instead, Purdue researchers have built sensors inspired by spiders, bats, birds and other animals, whose actual spidey senses are nerve endings linked to special neurons called mechanoreceptors.

The nerve endings—mechanosensors—only detect and process information essential to an animal’s survival. They come in the form of hair, cilia or feathers.

“There is already an explosion of data that intelligent systems can collect—and this rate is increasing faster than what conventional computing would be able to process,” said Arrieta, whose lab applies principles of nature to the design of structures, ranging from robots to aircraft wings.

“Nature doesn’t have to collect every piece of data; it filters out what it needs,” he said.

Many biological mechanosensors filter data—the information they receive from an environment—according to a threshold, such as changes in pressure or temperature.

A spider’s hairy mechanosensors, for example, are located on its legs. When a spider’s web vibrates at a frequency associated with prey or a mate, the mechanosensors detect it, generating a reflex in the spider that then reacts very quickly. The mechanosensors wouldn’t detect a lower frequency, such as that of dust on the web, because it’s unimportant to the spider’s survival.

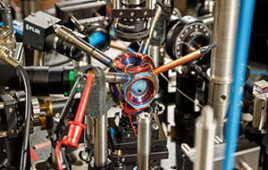

The idea would be to integrate similar sensors straight into the shell of an autonomous machine, such as an airplane wing or the body of a car. The researchers demonstrated in a paper published in ACS Nano that engineered mechanosensors inspired by the hairs of spiders could be customized to detect predetermined forces. In real life, these forces would be associated with a certain object that an autonomous machine needs to avoid.

But the sensors they developed don’t just sense and filter at a very fast rate—they also compute, and without needing a power supply.

“There’s no distinction between hardware and software in nature; it’s all interconnected,” Arrieta said. “A sensor is meant to interpret data, as well as collect and filter it.”

In nature, once a particular level of force activates the mechanoreceptors associated with the hairy mechanosensor, these mechanoreceptors compute information by switching from one state to another.

Purdue researchers, in collaboration with Nanyang Technology University in Singapore and ETH Zürich, designed their sensors to do the same, and to use these on/off states to interpret signals. An intelligent machine would then react according to what these sensors compute.

These artificial mechanosensors are capable of sensing, filtering and computing very quickly because they are stiff, Arrieta said. The sensor material is designed to rapidly change shape when activated by an external force. Changing shape makes conductive particles within the material move closer to each other, which then allows electricity to flow through the sensor and carry a signal. This signal informs how the autonomous system should respond.

“With the help of machine learning algorithms, we could train these sensors to function autonomously with minimum energy consumption,” Arrieta said. “There are also no barriers to manufacturing these sensors to be in a variety of sizes.”