By Mark Jones

By Mark Jones

In a normal world, vodka, nickel, palladium, and neon would have nothing in common. In our current world, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, they do. All are currently experiencing supply chain disruptions due either directly to the fighting or to sanctions.

Nickel and palladium come from mines. Russian mines produced about 10% of the world’s nickel and around 37% of the world’s palladium in 2021. This production is not easily replaced. The mineral deposits containing them are localized — not at all evenly distributed. It simply isn’t possible to ramp up production anywhere.

Vodka is a very different story. Vodka is associated with Russia and Russian vodka imports are being banned around the world. In reality, very little vodka consumed in the U.S. comes from Russia. The very Russian sounding Smirnoff vodka is made in Illinois. Vodka, it turns out, can be made from any fermentable substance. It can be distilled pretty much anywhere. It is like neon in that way.

Neon prices have jumped, skyrocketed even, due to Ukrainian production being shut down. It is not due to the shutdown of the Ukrainian neon mines. Neon doesn’t come from mines. It comes from the air. Air separation, the distillation of cryogenic liquified air, is the source of neon. Like vodka, neon can be distilled just about anywhere. Unlike nickel and palladium, the raw material for neon production is present all around the globe in equal concentration, around 0.0018%. Wherever you are, you are only a distillation column away from pure neon.

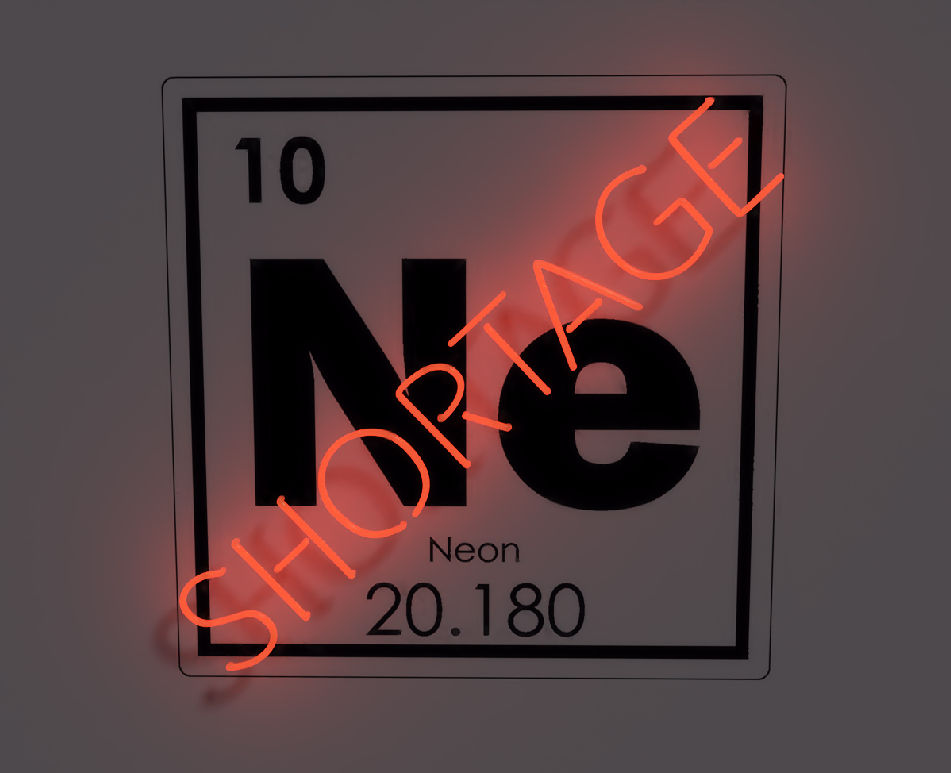

Mention of neon likely conjures the image of glowing glass signs. Neon still finds use there, but it is in the production of another kind of light where the shut down of Ukrainian production will be felt. It turns out neon is important for making semiconductor chips. Lack of neon will exacerbate and extend the semiconductor chip shortage.

Understanding the current neon shortage situation, and its impact on semiconductors, requires understanding why neon is important in manufacturing. It also requires understanding how Ukraine became the world’s largest supplier of a material anyone can make.

Neon is one of the noble gases, the column on the far right of the periodic table. The position of the noble gases on the table reflects that they have full electron orbitals, no unpaired electrons. As a result, they are inert. They don’t react to make compounds. Neon is important to the manufacture of semiconductor chips but is not present in the chips. It doesn’t directly touch the silicon during manufacturing. Neon helps make the deep ultraviolet (DUV) light used in the photolithographic process that patterns semiconductors. Neon plays a vital role in excimer lasers.

Patterning silicon to make circuits is a multistep process. Starting with a smooth surface, the surface is first completely covered with a photoresist. The photoresist is light sensitive. Light exposure causes chemical changes that allow parts of the photoresist to be washed away. In some types, the light exposed part is removed, in others the unexposed parts. A mask is placed over the photoresist covered surface. The mask blocks light from hitting some areas and exposes others to the light. Subsequent etching removes the exposed surface and leaves the area still covered by the photoresist unaffected. The wavelength of the light used in photolithography sets the smallest feature size that can be made. The higher the energy, the more that can be crammed onto the chip. Moore’s law is the result of the transition to shorter wavelengths. DUV lasers, at 193nm and 248nm, now are the workhorse light sources for the semiconductor industry. Up to 70% of the neon produced is in the service of the semiconductor industry. There are no semiconductor chips without DUV lasers. These lasers also find use in medicine and other manufacturing. Chips, with an already fractured supply chain, loom as a particular point of pain due to inadequate neon supplies.

Neon is only indirectly involved in the chemistry and physics of making UV light in an excimer laser. It is another of the noble gases, argon, where the action lies. Electrical discharges in a gas mixture containing argon, Ar, and fluorine, F2, can create a short-lived excited state molecule, (ArF)*. This transient molecule decomposes with the release of 193nm UV light. Position the discharge between two appropriate mirrors and a deep ultraviolet laser is the result. Neon is present primarily as the buffer gas, but does play a role as a collision partner, making up more than 95% of the mixture. Neon is there to do almost nothing, to serve as an inert carrier for the reacting argon and fluorine. Replacing neon is not really possible. There just aren’t other materials with its properties.

The chemistry of the excimer is surprisingly fragile. Impurities wreak havoc. The starting gases must be exceedingly pure. Laser operation ablates impurities from the cavity, adding impurities. The solution is to replace the gas after only weeks. The gases are scrubbed and vented. Neon and argon that were captured from the atmosphere are released back to the atmosphere. Neon and argon are part of a circular economy that nevertheless requires continual supplies of fresh, purified neon and argon. That is where the current situation in Ukraine enters the picture.

Air separation plants are expensive to build and operate. The products aren’t particularly difficult to transport, whether as a cryogenic liquid or compressed gas, but they are expensive to transport. Air separation plants generally serve a relatively local market or a large consumer. Distillation processes scale well, benefitting from what is commonly called the “two-thirds scale factor.” This is a mathematical relationship between how big something is and how much it costs to build. The capital investment to build an air separation plant grows at only 2/3 the rate of the capacity. Stated simply, bigger is better.

The neon industry in Ukraine takes advantage of very large air separation plants associated with steel manufacturing. These have economies of scale. They are a source of low-cost, crude neon-containing material that is a great starting point for making the purified neon used in lasers. Two manufacturers, Ingas and Cryoin, came to dominate the neon supply. They built on a feedstock advantage, gaining a further scale advantage. By some accounts, Ukraine was supplying about 70% of the world’s neon. Others estimate closer to 50%. No matter what the exact figure, the result is a dramatic and significant drop in the supply due to the war.

The current disruption is making many re-evaluate the global neon supply chain. It will likely lead to new entrants into the high-purity neon market. It is also causing a re-examination of neon use in excimer lasers. There is no replacement for neon, but use patterns are being examined in an effort to reduce consumption. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 prompted a flurry of research on reducing neon usage. Recycle systems for neon are commercially deployed, but are costly.

R&D can have an impact. Current efforts focus on making modular units capable of purifying spent excimer gases on site for reuse. Competing at very small scale is difficult. This leads some to propose return of the spent gas or partially purified spent gas to a central facility for recycle. Distillation is always energy intensive. Looking for alternative separation technologies, like membranes or absorbents may someday provide more economical separations at smaller scale.

We are now living through the second neon supply disruption caused by upheaval in Ukraine. The panic caused by the first dissipated as the political issues faded. The favorable cost position in Ukraine again returned it to the leading neon supplier. Only time will tell how seriously the neon supply chain is addressed as the current political situation resolves — and whether a material that can truly be made anywhere finds new production sites. It remains to be seen whether the current linear neon use transforms into a more circular neon economy.

Bwaha! Just brilliant to outsource steel and neon to the BRICS! Who needs semiconductors (while reading and replying to this 🙂 and neon lights, anyhow?

We cannot, in an age of fascists, permit governments to sell off scarce resources to just anyone.

Even with new Helium finds, allowing the gas to be used for trivial uses is insane.

Recycling is necessary for as much of everything we use as possible, to protect our environment and ourselves as well as to reduce our dependence upon the irreplaceable elements of our planet.

The pursuit of wealth and power regardless of cost–which has become the standard operating procedure for corporations–needs to change.

The easiest way to do so is to put ethical requirements into the corporate bylaws as bedrock. Management has long ago learned how to change or eliminate the laws which limit their profits by, for instance, making them pay to clean up their own messes.

No resource exploitation company which cannot manage to avoid polluting should have their lease rights and rights to operate in the industry–along with personal bans for all upper management and board members and anyone directly involved in causing damages.

The pursuit of wealth is what makes our lives all better, because a corporation can only sell their goods or services when the consumer sees an overall benefit to him/herself.A company becomes a corporation when it’s made millions of people better off because they reaped the benefits of that product or service. This pursuit leads to failure if cost is given no regard; the cost must be agreeable to the consumer in order for the business to sell their product or service.