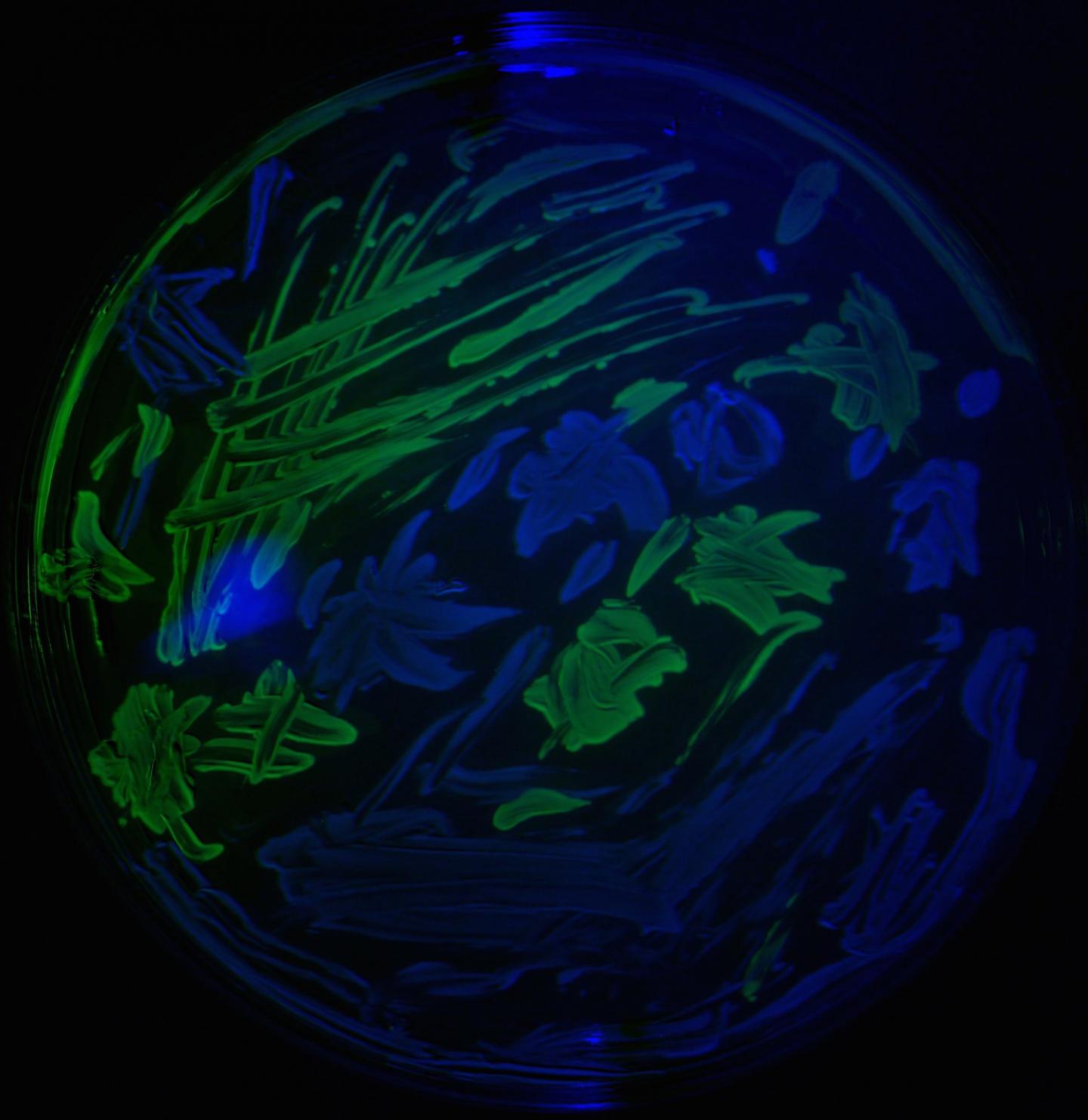

These are two types of lab E. coli smeared across an agar plate. The green ones are drug resistant and the blue ones are not. Credit: The University of Exeter

The growth of bacteria can be stimulated by antibiotics, scientists at the University of Exeter have discovered.

The EPSRC-funded researchers exposed E.coli bacteria to eight rounds of antibiotic treatment over four days and found the bug – which can cause severe stomach pain, diarrhoea and kidney failure in humans – had increased antibiotic resistance with each treatment.

This had been expected, but researchers were surprised to find mutated E.coli reproduced faster than before encountering the drugs and formed populations that were three times larger because of the mutations.

This was only seen in bacteria exposed to antibiotics – and when researchers took the drug away, the evolutionary changes were not undone and the new-found abilities remained.

“Our research suggests there could be added benefits for E.coli bacteria when they evolve resistance to clinical levels of antibiotics,” said lead author Professor Robert Beardmore, of the University of Exeter.

“It’s often said that Darwinian evolution is slow, but nothing could be further from the truth, particularly when bacteria are exposed to antibiotics.

“Bacteria have a remarkable ability to rearrange their DNA and this can stop drugs working, sometimes in a matter of days.

“While rapid DNA change can be dangerous to a human cell, to a bacterium like E.coli it can have multiple benefits, provided they hit on the right changes.”

The researchers tested the effects of the antibiotic doxycycline on E.coli as part of a study of DNA changes brought about by antibiotics.

The E.coli “uber-bug” that subsequently evolved was safely frozen at -80C and the scientists used genetic sequencing to find out which DNA changes were responsible for its unusual evolution.

Some changes are well known and have been seen in clinical patients, like E.coli producing more antibiotic pumps that bacteria exploit to push antibiotics out of the cell.

Another change saw the loss of DNA that is known to describe a dormant virus.

“Our best guess is that losing viral DNA stops the E.coli destroying itself, so we see more bacterial cells growing once the increase in pump DNA allows them to resist the antibiotic in the first place,” said Dr Carlos Reding, who was part of the study.

“This creates an evolutionary force for change on two regions of the E.coli genome.

“Normally, self-destruction can help bacteria colonise surfaces through the production of biofilms. You see biofilms in a dirty sink when you look down the plughole.

“But our study used liquid conditions, a bit like the bloodstream, so the E.coli could give up on its biofilm lifestyle in favour of increasing cell production.”

Dr Mark Hewlett, also of the University of Exeter, added: “It is said by some that drug resistance evolution doesn’t take place at high dosages but our paper shows that it can and that bacteria can change in ways that would not be beneficial for the treatment of certain types of infection.

“This shows it’s important to use the right antibiotic on patients as soon as possible so we don’t see adaptations like these in the clinic.”