The Expedition 45 crew gathers inside the Destiny laboratory to celebrate the 15th anniversary of continuous human presence aboard the International Space Station. Front row: Japanese astronaut Kimiya Yui (left) and NASA astronauts Scott Kelly (middle) and Kjell Lindgren. Back row: Russian cosmonauts Sergey Volkov (left), Oleg Kononenko (middle) and Mikhail Kornienko (right). Yui is seen holding the mission patch for Expedition 1 which arrived at the station on Nov. 2, 2000. Credit: NASA Flickr

When most people think of archaeology, images of bones, ancient artifacts, and dig sites come to mind.

But Justin Walsh, Ph.D. and Alice Gorman, Ph.D. are taking a new approach to archaeology—trading in their shovels and picks for something out of this world, literally.

The two have launched ISS Archaeology, the first archaeological study of a space habitat.

They are working to understand the evolving cultural, social, and material structure of the International Space Station (ISS), which has been continuously occupied by between two and six astronauts for nearly 17 years.

They hope their work will demonstrate to NASA and other space agencies the importance of incorporating social sciences into space research, said Walsh, associate professor, Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, Chapman University, in an interview with R&D Magazine.

“The whole reason to have the ISS is to help plan for long duration missions, much longer than even the year that Scott Kelly did,” said Walsh. “NASA has done decades of physiological and psychological research on the impact and consequences of long duration space missions. But they have never done a study on the society or the culture that does form in a space craft.”

The ISS project has involved five space agencies—America’s NASA, Russia’s Roscosmos, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA.) Astronauts from 25 nations, countless private contractors, and at least 222 visitors from 18 countries have come to the ISS. Currently there are six astronauts occupying the station.

The ISS represents a unique opportunity to study human adaptation to a unique, ‘micro-society in a mini world,’ said Walsh, one that is multi-ethnic, multi-gender, and multi-lingual.

Astronauts on the ISS live in tight quarters, with limited access to the outside world. In addition, they experience a constant state of microgravity, a concept that is particularly interesting to Walsh and Gorman.

“All archaeology on Earth is about cultures in one particular gravity regime. It’s a constant environmental factor in everything we do,” said Gorman, senior lecturer, department of Archaeology, Flinders University, Australia in an interview with R&D Magazine. “By removing gravity, we have, for the first time, the opportunity to do an experiment which will tell us just how much of human material culture and behavior is structured by Earth gravity. Investigating the intersection of gravity, technology and society is a necessary step, I think, in planning for future space habitation.”

Studying space from Earth

Studying the ISS, a place that Gorman and Walsh cannot physically visit, is a challenge.

“We can conceptualize these spaces, but we can’t go there and look at it, we can’t inspect it, we can’t see where items are located, we can’t see how the material culture that remains there reflects human activity in the past,” said Walsh. “So we had to think outside the box.”

Fortunately, the development of the ISS and the rise of digital photography coincided, resulting in an estimated 1 million digital photographs from the ISS taken since 2000. These files come with metadata, which provides critical information on exactly when each file was taken.

Analyzing the material culture visible in these photos, as well as how people associate with the items, will reveal a lot about the society and culture of the ISS, said Walsh.

“One photograph we have shows a few astronauts in the Zvezda Russian command module. They have a table right next to them and it has food on it. They have pictures up on the wall, paintings and photographs. They have a gold orthodox cross and a Russian flag. They have toys in various places. There is a whole slew of cultural items there,” said Walsh.

“We can document all of that, and document the associations between the crew and those spaces and those items, just by looking at those images and classifying those items, and people, and places into the database,” Walsh continued. “Ultimately, what we can do is build maps of patterns of behavior or patterns of association. We may find that certain countries tend to be in certain areas, or that there are gender patterns or patterns based on who has military backgrounds, as opposed to civilians. Material culture can reveal aspects of our world to us that are not visible in other ways.”

Walsh and Gorman are currently working with NASA to get full access to all of the images taken inside the ISS and access the ISS inventory management system, which catalogs all non-personal items in the station. They wrote a proposal to NASA in January of this year and received a letter of feasibility in March, which indicates that the organization does not see any difficulties with providing them this information, assuming they promise to keep the identities of the astronauts anonymous. Walsh and Gorman are currently waiting to hear if they have received a grant to fund this research from the National Geographic Society.

For now, they are working with publically available photos of the ISS. Over 7,000 photos of the interior of the ISS are available on NASA’s Johnson Space Center Flickr account.

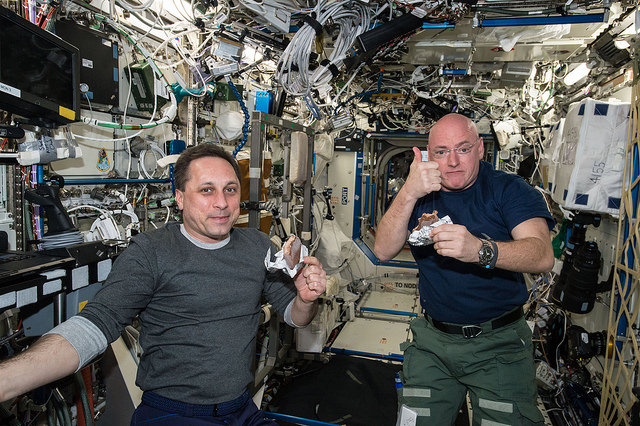

NASA astronaut Scott Kelly gives the “high sign” on the quality of his snack while taking a break from his work schedule aboard the International Space Station on Apr. 20, 2015. Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko (ROSCOSMOS) seems to agree on the tasty factor of the specially prepared space food. Credit: NASA Flickr

Incorporating machine learning

Because there will be so many photos to go through and classify, Walsh and Gorman are working with Erik Linstead—a colleague of Walsh’s who specializes in machine learning— to create a database that can comb through the images and classify them by what material items are included, who is in them, and when and where they were taken.

They also plan to utilize crowd sourcing as a way to classify images, presenting photos of the ISS to the public and asking them to help identify the item and actions in them. This concept was first popularized by Zooniverse, an online platform for people-powered research. Walsh and Gorman are currently gathering potential “researchers” via their social media platforms on Twitter, and Facebook.

Eventually, the team hopes to use all of this data to create a 3D model of the ISS with the images appearing over the areas they were taken. The photos would be indexed by date and time, so a user could move a slider and select practically any moment in the space station’s history and observe what was occurring. Walsh feels this technique could be applied elsewhere in archeology.

“You can imagine there are other kinds of archeological sites that you can’t easily go to; the Titanic, Antarctic research stations, locations in hostile or dangerous countries,” said Walsh. “This would allow archeologists to take a view of the site and its development over time without actually being there. This could be a way of opening up new kinds of archeological investigations in other contexts.”

Understanding the ISS

Although the team does not yet have access to the full collection of ISS photos, they have begun learning about its culture from the collection available online. Gorman has found the use of ziplock bags on the ISS particularly interesting.

“I looked at images which showed snap lock or ziplock bags on the ISS,” she said. “Analyzing their context of use led me to conceptualize them as a ‘gravity surrogate’: because objects float away so easily in microgravity, ziplock bags are used to restrain them and simulate an Earth gravity environment so that the astronauts can get on with their jobs. I’m quite keen to find out what else, apart from the obvious straps and Velcro, is used as a gravity surrogate.”

Walsh mentioned his interest in understanding how issues of privacy impact those living on the ISS. Throughout the ISS’s history, there has not always been as many crew compartments as there were crew, meaning an ‘odd man out,’ had to find somewhere else to sleep. Early in the station’s history, there were three crewmembers and only two compartments, and soon, when a planned seventh astronaut joins the ISS crew, there will again be one extra person, as the ISS currently only has six crew compartments.

“When one person has to find another place to sleep, I’m interested to understand how this impacts privacy, comfort, and a sense of hierarchy aboard the ISS,” said Walsh.

He is also interested in issues of competition, as well as intimacy among members of the crew.

“There are larger crews living together for longer periods of time, we have different genders living together, to what extent that makes a difference, or doesn’t,” said Walsh. “In any case, we do wonder to what extent intimacies develop among crews, especially considering there is so little privacy.”

Understanding this may be hard, as there could be bias in the types of photos that were taken on ISS, said Walsh. The institution, or the astronauts themselves, may be trying to preserve a certain image. However, learning more about the image people are trying to present is interesting in itself, said Walsh.

Regardless of what they learn, Walsh and Gorman’s ultimate hope is to legitimize the importance of this sort of research.

“Many in the space sector seem to think that humanities and social sciences are not rigorous, which leads to them ignoring major fields of research—and expressing views about human behavior which are embarrassingly naïve,” said Gorman. “As archaeologists, we’re used to working in large multidisciplinary teams, so we’re definitely ready to build and cross those bridges.”