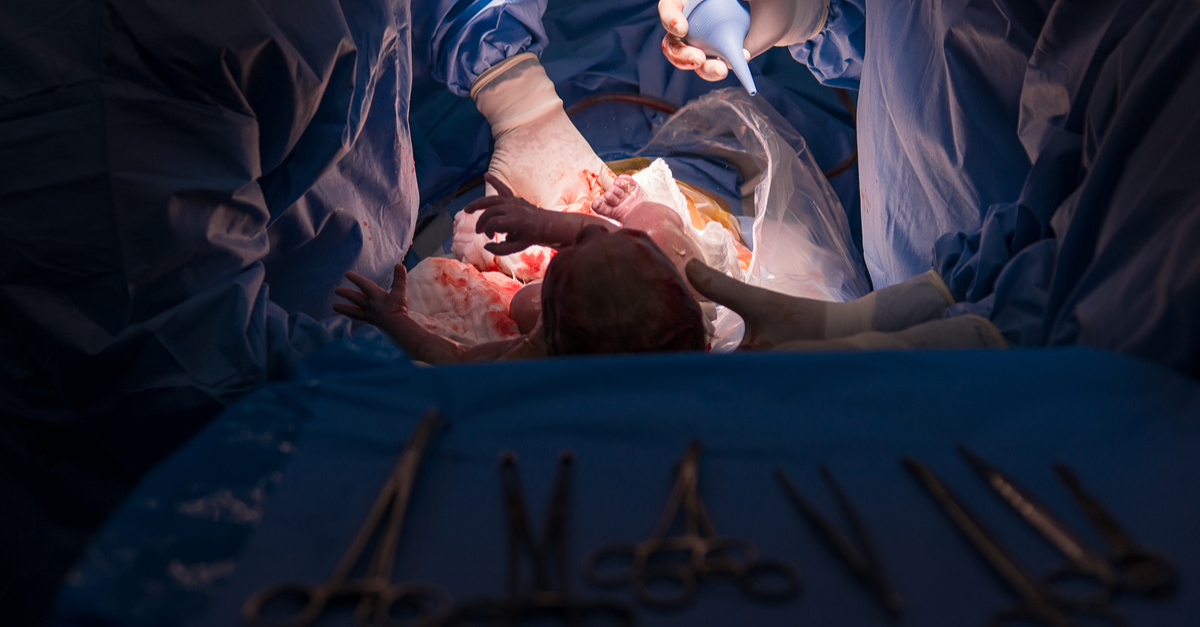

Researchers estimate that the regular use of cesareans has led to a 10 to 20 percent spike in the gap between female pelvis width and the babies’ size.

What if you were told that there’s a method to that emergency C-section madness that you’ve had or that your wife has gone through?

A new study has found statistical evidence that an increase in the number of mothers giving birth via cesarean section (the surgical delivery of a baby) over the past several decades has been causing an evolutionary change, which has led to a larger gap between the size of females’ pelvises and the heads of babies—meaning babies’ heads are getting bigger while the birth canal remains status quo.

Researchers from Austria and the U.S. estimate that the regular use of C-sections has led to a 10 to 20 percent spike in the gap between female pelvis width and the babies’ size.

It is no secret that human birth is much more involved and difficult than that of other species. When a baby is too big to pass though—known as fetopelvic disproportion—surgeons manually remove the child through an incision in the woman’s lower abdomen. The procedure has been called a Cesarean from Julius Caesar, as legend has it that he had been cut from his dying mother’s womb. C-sections for births have been used safely and regularly since the 1950s and 60s.

“We wanted to understand why the rate of birth complications, in particular fetopelvic disproportion, is so high in humans. In primates, childbirth is much easier because the neonatal head is smaller compared to the maternal birth canal. From an evolutionary perspective, it has been puzzling why humans did not evolve a wider pelvis in order to ease childbirth,” study lead author Philipp Mitterocker, an assistant professor with the Department of Theoretical Biology at the University of Vienna, Austria, told R&D Magazine in an exclusive interview.

One argument for human birth being more difficult was because women need to have smaller pelvises to walk, which the professor sees as a weak one. He argues that a narrower pelvis is important to support the inner organs and fetus.

“It seemed not very convincing to us how the (probably minor) advantages for locomotion can compensate the fitness loss of a population resulting from obstructed labor,” Mitterocker added. “We wanted to explain how such a seemingly paradoxical situation could have evolved.”

The researchers devised a mathematical model that shows this apparent “sub-optimality” can result from evolution by natural selection. They used logic and math to come to that conclusion. The logic suggests that if babies with over-large heads survive to adulthood, rather than dying at birth, as was the case for most human history, and thereby carrying the genes for larger heads, then more babies with the same genes will be born in the future—medical data show that larger newborns have higher survival rates and are less affected by several diseases. To back up their theory, the researchers downloaded birth data numbers over the past half-century and found that the global rate of fetopelvic disproportion has grown from 3 percent of births in the 1960s to 3.3 percent of births today.

On the maternal side, narrow pelvises seem to be more advantageous, contributing to the tightness of the canal relative to baby`s cranium. Aside from putative biomechanical advantages of narrow pelvises for bipedal locomotion, wide pelvises are associated with higher risks of organ prolapse and similar defects. However, fitness increases only to the point where the baby does not fit through the birth canal any more. In other words, childbirth constitutes a selective pressure, according to Mitterocker.

“When C-sections (luckily) remove this selective constraint, only selection for larger babies and/or narrower pelvis remains, which is expected to change these anatomical dimensions in modern humans,” he said.

So what does that mean for the future of humans and birth? While the disproportion might further increase, Mitterocker doesn’t see every baby being born via C-section one day. The selection towards larger babies is limited by the mother’s metabolic capacity and also attenuated by modern medical treatment: also newborns with less weight or prematurely born babies have high survival rates in industrialized countries. The same holds for wider pelvises: organ prolapse is rarely lethal nowadays, he concluded.

The results of this analysis were published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.