For pharmaceutical, biotech, and medical device manufacturers that operate in cleanroom environments, the cleaning and disinfection of surfaces in their controlled environments are cornerstone elements of their contamination control programs. Any deficiency or shortcoming in a contamination control program can lead to expensive investigations, production stoppages, and costly product recalls. Despite the critical role that effective surface decontamination plays in the production of safe and effective medicines, especially for sterile products produced by aseptic processing, too many facilities continue to struggle with the basics of cleaning and disinfection. This article highlights some of the tactics that manufacturers can deploy to strengthen their cleaning and disinfection programs.

One of the greatest challenges that operators face in effectively decontaminating cleanroom surfaces is that there is no immediate feedback on how well they are performing their tasks. In most instances, cleanroom surfaces (i.e. floors, walls, and equipment) already appear to be visually “clean”. Operators tasked with cleaning surfaces for the next production shift are often mopping and wiping surfaces that, to the naked eye, appear to be clean. Cleanroom operators attempting to remove sub-visible particulates and microbial contaminants without the benefit of visible cue are, in effect, dealing with an invisible challenge. It is easy to see when a visibly soiled surface has been effectively cleaned; the difference between visibly dirty and visibly clean is evident. In contrast, cleanroom operators must employ strict methodical and systematic techniques to effectively decontaminate surfaces, because there are no visual cues that their efforts are effective.

Most companies do a suitable job of training their cleanroom employees on the required methodology for cleaning and disinfection of surfaces. There is a wealth of educational resources that employers can roll out to their workforce on the subject. Cleaning and disinfection curricula often include computer-based training and videos, in addition to the required reading of applicable standard operating procedures (SOPs). It is common for employers to include a quiz at the end of the module(s), ostensibly to demonstrate competency. However, training does not equal learning, and it is an unfortunate fact that employees can successfully complete a company’s required training and still never truly grasp the criticality and highly technique-dependent nature of disinfectant cleaning. To establish a true competency-based learning curriculum for cleaning and disinfection, companies must use qualified subject matter experts as trainers and use first-hand observations, on a continuing basis, to ensure that the methodical and systematic techniques required for effective disinfectant cleaning are indeed being carried out by the cleanroom operators.

The 1984 blockbuster film The Karate Kid introduced the phrase “Wax on, wax off ” to our lexicon, and it feels natural to use this technique when wiping surfaces. Indeed, it may be effective when scrubbing pots and pans at the kitchen sink (or waxing a 1948 Ford Super Deluxe convertible). However, when the goal is to remove sub-visible particulates from surfaces, the “wax on, wax off ” technique — despite feeling like human nature — can be disastrous for cleanroom surfaces.

Fig. 1: Surface contamination. Image: Joe McCall

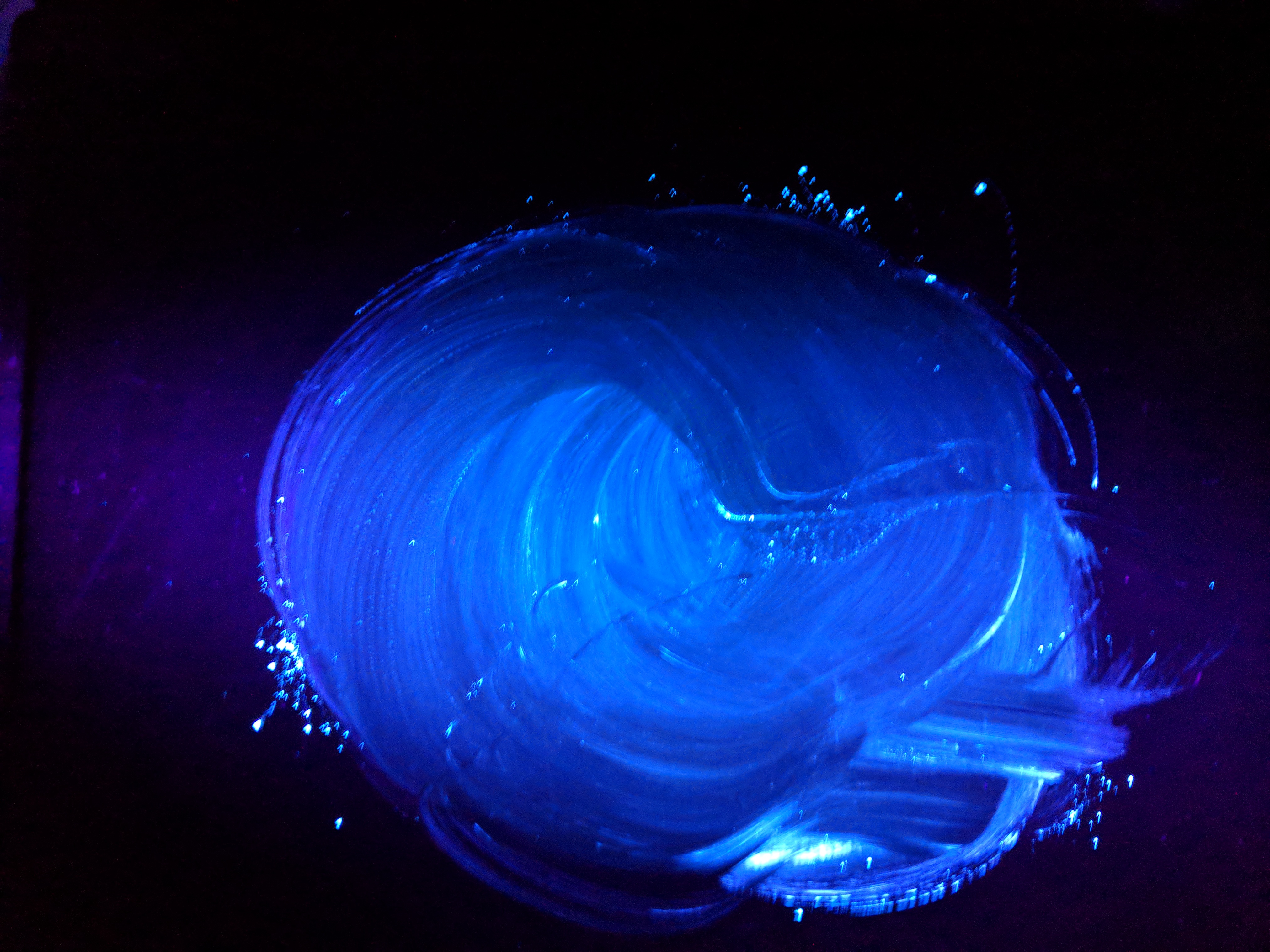

Refer to Fig. 1, where a fluorescent powder was sprinkled onto a surface. It is visually evident that the surface is soiled. Using the “wax on, wax off ” method with a saturated wipe, one can achieve a visually clean surface. Under ultraviolet light, however (see Fig. 2), it becomes apparent that this technique has only spread the contaminant around and ground it into crevices of the surface imperfections.

Fig. 2: Effect of wiping surface with rotational technique. Image: Joe McCall

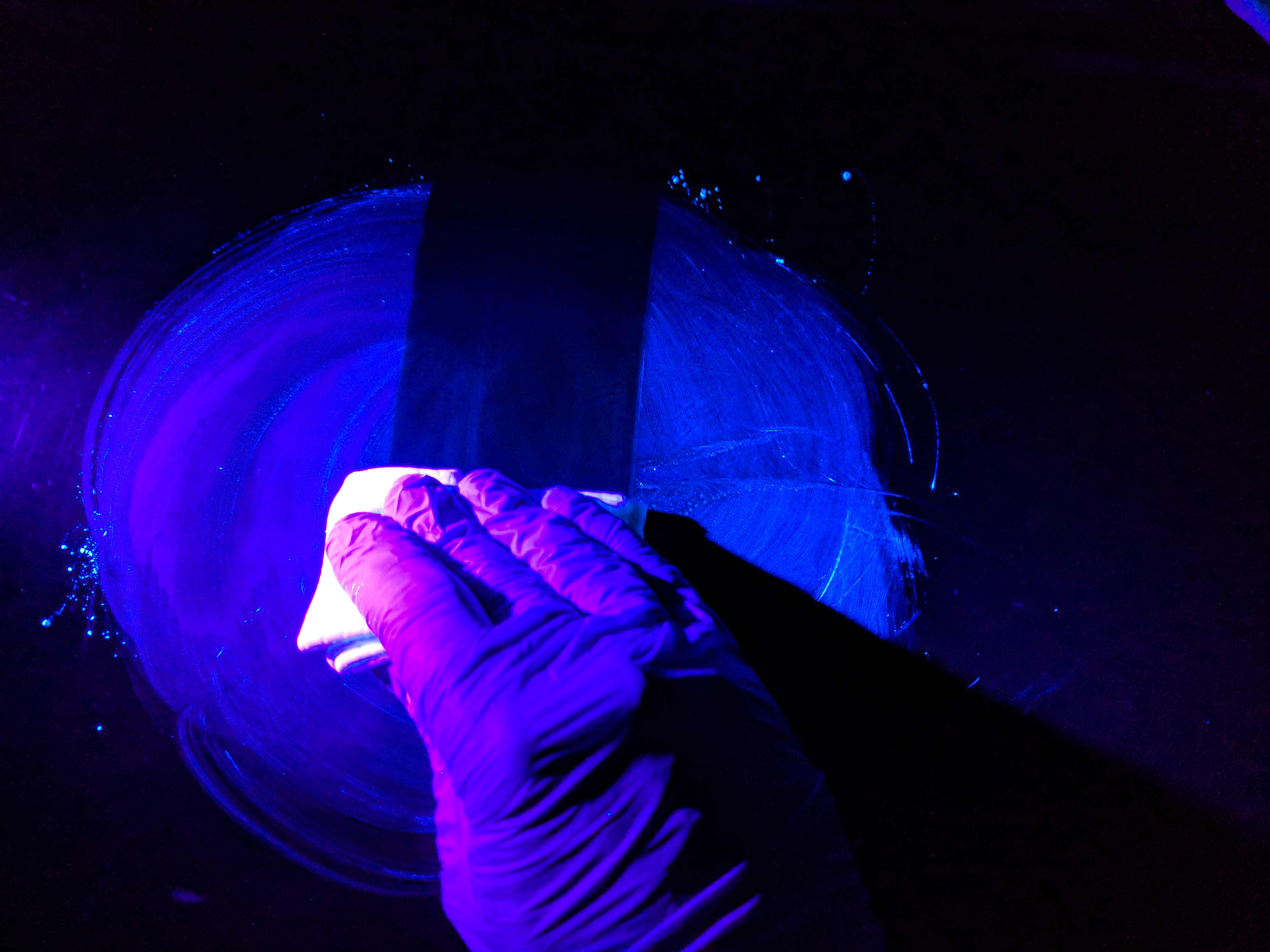

Using a single pass stroke with a saturated wipe (Fig. 3) is a proven, effective way to remove subvisible particulates from surfaces.

Fig. 3: Removal of sub-visible particulate using correct technique. Image: Joe McCall

As noted earlier, most companies do have sufficient training materials addressing these techniques. It is a training standard that cleanroom disinfection is performed from cleanest (or most critical) to dirtiest (or least critical). Overlapping top-to-bottom unidirectional strokes is the norm for mopping of walls. It is essential that cleanroom operators truly comprehend the reasons for these techniques, however, since there is no immediate visual feedback for the operator if they’ve missed a spot or section. One can’t turn on a blacklight and see where cleaning and disinfection were ineffective. Therefore, strict adherence to systematic and methodical technique is required. The idea that employees have to be mindfully engaged in the task in order to successfully perform it must be conveyed to and truly understood by the cleanroom operator.

Enforcement of this approach is where some companies may fall short. It is imperative that front line supervisors conduct in-person assessments of technique for cleaning and disinfection, and that the assessments be done at some frequency (e.g., bi-weekly, monthly, or quarterly). Review of technique should not be a paper exercise or conducted solely by video review in a conference room. The very best supervisors engage employees on the floor at the time of cleaning and disinfection and ensure that proper technique is used. They reinforce the critical nature of the task and empower their employees to give feedback on opportunities to optimize the cleaning and disinfection program. No one knows how well the mops work better than the people who are handling the mops.

Cleanroom employees should feel empowered to provide feedback on the tools of their trade, and management should listen. If a mop handle is unwieldy, or a bucket system is difficult to manage, then the effectiveness of cleaning and disinfection will suffer. The draft revision of EU Annex 1 Manufacture of Sterile Medicinal Products goes so far as to say that employees must have appropriate “…attitudes with a specific focus on the principles involved in the protection of sterile product…”.1 It is not acceptable for cleanroom operators to simply “read and understand” an SOP on cleanroom disinfection and undergo a perfunctory assessment via

a multiple-choice quiz. Management in the cleanroom industry must ensure that their operators are provided with the knowledge, skills, and tools to suitably and effectively prepare their cleanroom surfaces for safe production.

During several recent audits, the proper techniques for wiping and mopping in cleanrooms were identified as root causes for recurring fungal and bacterial spore contaminations. One example included review of video surveillance of the thirdshift cleaning and disinfection program, which showed the disinfectant was applied like car wax in circular motions on the walls and filling equipment. The proper technique is overlapping unidirectional strokes. During another audit, a single mop head was used for cleaning all the walls and floors in the cleanroom and the same wipe was used to clean all the surfaces in the BSL hood. Conducting periodic audits and observing video surveillance of the cleanroom cleaning can reveal opportunities for improvement in your overall contamination control program. During another visit to a compounding pharmacy, employees were observed using their hands to wring out mops and wipes in the cleanroom, clearly demonstrating the need for training by a subject matter expert.

Poor cleaning methods can lead to mold growth and spreading of fungal spores in the cleanroom as highlighted in a recent FDA warning letter, “An area of the ceiling spanning across at least two HEPA filters (b)(4) the (b)(4) had dark stains on the ceiling frame and the HEPA filters. Your routine cleaning of the cleanroom does not cover cleaning of the ceiling and HEPA filters which are only replaced when there is damage.”2

PDA’s Technical Report number 703 identifies training as a critical element of a cleaning and disinfection program and regulatory auditors are certainly holding manufacturers accountable, as these observations show:

“Specifically, your firm stores mop buckets used in the cleaning of the Class 100 vial fill suites in a closet in an unclassified area. Your firm has no documentation to show that the mop buckets are appropriately sanitized before being taken into the Class 100 areas. In addition, the disinfectant used to clean the floors and walls is added to the mop buckets in an unclassified area. The filled mop buckets are then carried through an unclassified area before entering the Class 100 vial fill suites.”4

“Your firm failed to use disinfectant agents that are appropriate for use for cleaning the (b)(4), the (b)(4), and the (b)(4), which are located inside the aseptic processing area. For example, you use non-sterile (b)(4) and non-sterile wipes and do not use a sporicidal agent.”5

“Your firm failed to establish and follow appropriate written procedures that are designed to prevent microbiological contamination of drug products purporting to be sterile, and that include validation of all aseptic and sterilization processes (21 CFR 211.113(b)). Your firm failed to establish an adequate system for cleaning and disinfecting the room and equipment to produce aseptic conditions (21 CFR 211.42(c)(10)(v)).”6

Fig. 4: Mold contamination on wall. Image: Courtesy of Dan Klein/Jim Polarine

Training in aseptic processing, basic microbiology, basic chemistry, and cleaning and disinfection must be provided to new operators. Refresher training must occur on a continuing basis. Regulatory bodies and industry itself have raised the bar where training is concerned. Effective training can only be performed by truly competent, qualified instructors with demonstrable expertise in the topics. Trainees are expected to demonstrate their proficiency in the skills they learn. Competency-based learning is replacing the old and ineffective training model of simply reading binders of SOPs. For critical environments, it is a welcome shift and can only lead to greater safety for patients.

References

1. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/gmp/2017_12_pc_annex1_consultation_document.pdf

2. FDA Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations, Warning Letter 31-17, May 17, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/iceci/enforcementactions/warningletters/2017/ucm560653.htm

3. PDA Technical Report No. 70 (2015). Fundamentals of Cleaning and Disinfection Programs for Aseptic Manufacturing Facilities. Available from Parenteral Drug Association, Inc.

4. GMP Trends Issue #935 January 1, 2016, Published by GMP Trends, Inc. Boulder, Colo.

5. FDA Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations, Warning Letter OBPO 1 17-02, Aug. 24, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/iceci/enforcementactions/warningletters/2017/ucm573187.htm

6. FDA Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations, Warning Letter CMS Case # 522183, Aug. 9, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/iceci/enforcementactions/warningletters/2017/ucm572086.htm

Joe McCall, SM (NRCM), is a Technical Service Specialist with Steris Corp. Jim Polarine Jr., MA., is a Senior Technical Service Manager with Steris Corp. www.steris.com