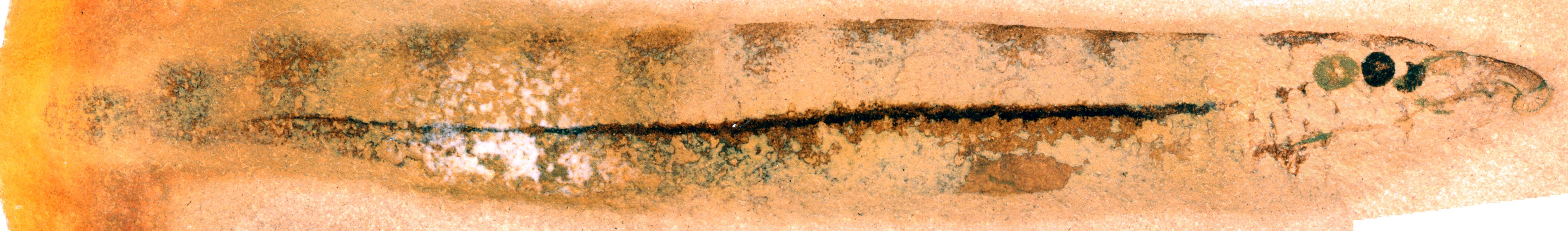

The fossil of a 300-million-year-old primitive jawless fish — a lamprey — about 6 cm in length. The eyes are the two dark circles on the right-hand side and are so well-preserved the retina and lens can be seen in high magnification. Credit: Rober Sansom

New research led by the University of Leicester has overturned a long-standing theory on how vertebrates evolved their eyes by identifying remarkable details of the retina in the eyes of 300 million year-old lamprey and hagfish fossils.

The study, published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, led by Professor Sarah Gabbott from the University of Leicester Department of Geology, shows that fossil hagfish eyes were well-developed, indicating that the ancient animal could see, whereas their living counterparts are completely blind after millions of years of eye degeneration – a kind of reverse evolution.

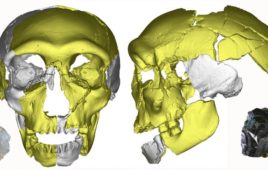

The researchers examined the eye tissue in two fossil jawless fish species – Mayomyzon (a lamprey) and Myxinikela (a hagfish) found in the Carboniferous age Mazon Creek fossil bed, Illinois.

Using a high-powered scanning electron microscope to magnify the eye 5,000 times they could see that the fossil retina is composed of minute structures called melanosomes – the same structures that occur in human eyes and prevent stray light bouncing around in the eye allowing us to form a clear visual image.

This is the first time that such details in fossil vertebrate eyes have been brought to bear on the tricky problem of how their eyes evolved.

The eye is a complex structure and must have evolved through small step-by-step changes but these are not recorded in living animals and until now it was thought that these anatomical details could not be preserved in fossils.

Professor Gabbott explains: “To date models of vertebrate eye evolution focus only on living animals and the blind and ‘rudimentary’ hagfish eye was held-up as critical evidence of an intermediate stage in eye evolution. Living hagfish eyes appeared to sit between the simple light sensitive eye ‘spots’ of non-vertebrates and the sophisticated camera-style eyes of lampreys and most other vertebrates.”

The details of the retina in the fossil hagfish indicates that it had a functional visual system, meaning that living hagfish eyes have been lost through millions of years of evolution, and these animals are not as primitively simple as we originally believed. As a result they are not the most appropriate model for understanding eye evolution.

Professor Gabbott added: “Sight is perhaps our most cherished sense but its evolution in vertebrates is enigmatic and a cause célèbre for creationists. We bring new fossil evidence to bear on an iconic evolutionary problem: the early evolution of the vertebrate eye. We will now scrutinize the eyes of other ancient vertebrate fossils to see if we can finally build a picture of the sequence of events that took place in early vertebrate eye evolution.”

The team also found the earliest evidence of skin pigment patterning in a fossil.

She added: “This heralds the realistic possibility of inferring details of the ecology and behavior of our ancient ancestors. Animals today have stripes for many reasons from camouflage to sexual display- we now have the potential to understand behavior in long extinct vertebrates.”