It has long been recognized that AI can achieve a higher level of performance than humans in various games, but until now, physical skill remained the ultimate human prerogative. This is no longer the case. An AI technique known as deep reinforcement learning has pushed the limits of what can be achieved with autonomous systems and AI, achieving superhuman performance in a variety of different games such as chess and Go, video games, and navigating virtual mazes. Today, artificial intelligence is beginning to push the boundaries and gain ground on man’s prerogative: physical skill.

ETH Zurich researchers have created an AI robot that learns, in only 6 hours, to execute a popular game of physical skill in record time.

Researchers at ETH Zurich have created an AI robot named CyberRunner whose task is to learn how to play the popular and widely accessible labyrinth marble game. The labyrinth is a game of physical skill whose goal is to steer a marble from a given start point to the endpoint. In doing so, the player must prevent the ball from falling into any of the holes that are present on the labyrinth board.

The movement of the ball can be indirectly controlled by two knobs that change the orientation of the board. While it is a relatively straightforward game, it requires fine motor skills and spatial reasoning abilities, and, from experience, humans require a great amount of practice to become proficient at the game.

CyberRunner applies recent advances in model-based reinforcement learning to the physical world and exploits its ability to make informed decisions about potentially successful behaviors by planning real-world decisions and actions into the future.

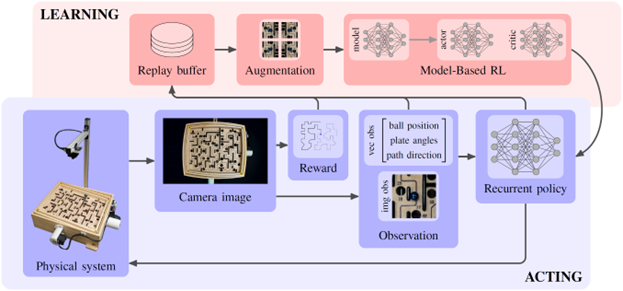

Just like us humans, the robot learns through experience. While playing the game, it captures observations and receives rewards based on its performance, all through the “eyes” of a camera looking down at the labyrinth. A memory is kept of the collected experience. Using this memory, the model-based reinforcement learning algorithm learns how the system behaves, and based on its understanding of the game, it recognizes which strategies and behaviors are more promising (the “critic”). Consequently, the way the robot uses the two motors (its “hands”) to play the game is continuously improved (the “actor”). Importantly, the robot does not stop playing to learn; the algorithm runs concurrently with the robot playing the game. As a result, the robot keeps getting better, run after run.

The learning on the real-world labyrinth is conducted in 6.06 hours, comprising 1.2 million time steps at a control rate of 55 samples per second. The AI robot outperforms the previously fastest recorded time, achieved by an extremely skilled human player, by over 6%.

Interestingly, during the learning process, CyberRunner naturally discovered shortcuts. It found ways to “cheat” by skipping certain parts of the maze. The lead researchers, Thomas Bi and Prof. Raffaello D’Andrea of ETH Zurich, had to step in and explicitly instruct it not to take any of those shortcuts.

A preprint of the research paper is available on the project website, where Bi and D’Andrea will open source the project.

“We believe that this is the ideal testbed for research in real-world machine learning and AI. Prior to CyberRunner, only organizations with large budgets and custom-made experimental infrastructure could perform research in this area,” said D’Andrea. “Now, for less than 200 dollars, anyone can engage in cutting-edge AI research. Furthermore, once thousands of CyberRunners are out in the real-world, it will be possible to engage in large-scale experiments, where learning happens in parallel, on a global scale. The ultimate in Citizen Science!”

Watch ETH Zurich’s video:

Tell Us What You Think!