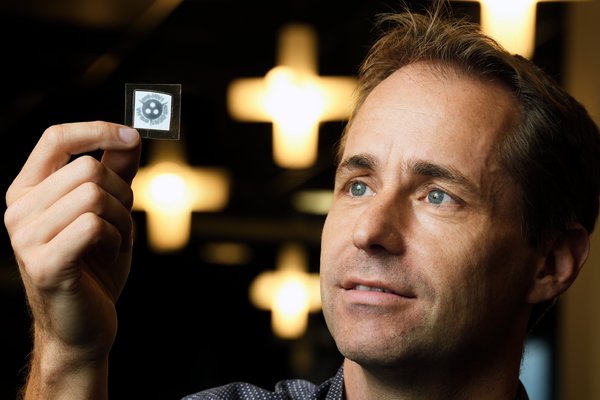

Research leader Maarten Merkx with one copy of the ‘glow-in-the-dark’ test. Image: Bart van Overbeeke

Researchers from Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e) and Keio University have presented a practicable and reliable way to test for infectious diseases. All you need are a special glowing paper strip, a drop of blood, and a digital camera, as they write in the scientific journal Angewandte Chemie.

Not only does this make the technology very cheap and fast — after just 20 minutes it is clear whether there is an infection — it also makes expensive and time-consuming laboratory measurements in the hospital unnecessary.

In addition, the test has a lot of potential in developing countries for the easy testing of tropical diseases.

The test shows the presence of infectious diseases by searching for certain antibodies in the blood that your body makes in response to, for example, viruses and bacteria.

The development of handy tests for the detection of antibodies is in the spotlight as a practicable and quick alternative to expensive, time-consuming laboratory measurements in hospitals. Doctors are also increasingly using antibodies as medicines, for example in the case of cancer or rheumatism.

This simple test is also suitable for regularly monitoring the dose of such medicines to be able to take corrective measures in good time.

The use of the paper strip developed by the Dutch and Japanese researchers is a piece of cake. Apply a drop of blood to the appropriate place on the paper, wait twenty minutes and turn it over.

“A biochemical reaction causes the underside of paper to emit blue-green light,” says Eindhoven University of Technology professor and research leader Maarten Merkx.

“The bluer the color, the higher the concentration of antibodies.”

A digital camera, for example from a mobile phone, is sufficient to determine the exact color and thus the result.

The color is created thanks to the secret ingredient of the paper strip: a so-called luminous sensor protein developed at TU/e.

After a droplet of blood comes onto the paper, this protein triggers a reaction in which blue light is produced (known as bioluminescence).

An enzyme that also illuminates fireflies and certain fish, for example, plays a role in this. In a second step, the blue light is converted into green light.

But here is the clue: if an antibody binds to the sensor protein, it blocks the second step. A lot of green means few antibodies and, vice versa, less green means more antibodies.

The ratio of blue and green light can be used to derive the concentration of antibodies.

“So not only do you know whether the antibody is in the blood, but also how much,” says Merkx.

By measuring the ratio precisely, they suffer less from problems that other biosensors often have, such as the signal becoming weaker over time.

In their prototype, they successfully tested three antibodies simultaneously, for HIV, flu and dengue fever.

Merkx expects the test to be commercially available within a few years.