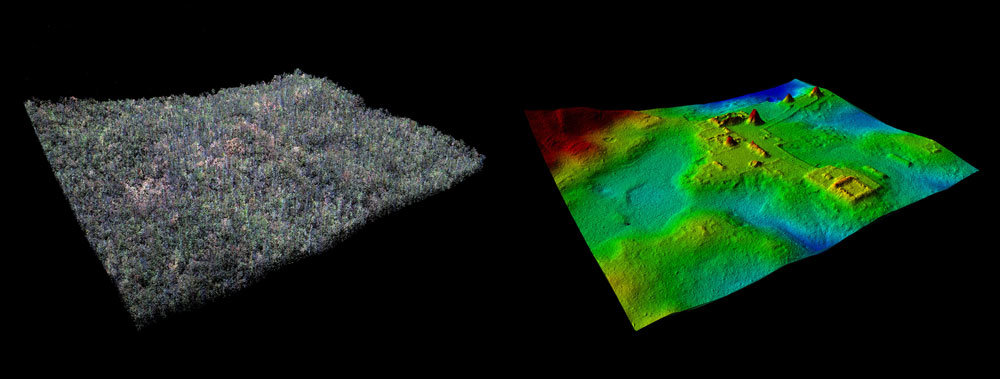

A comparison of LiDAR data showing the ancient Maya site of El Zotz covered in trees (left), and with the trees digitally removed. Credit: Ithaca College

Researchers have taken to the sky in an attempt to learn about what is hidden on the ground in Guatemala from ancient Mayan civilizations.

A recently conducted survey of 2,100-square kilometers has uncovered over 60,000 previously unknown structures using LiDAR, including unknown pyramids, palace structures, terraced fields, roadways, defensive walls and towers and houses amongst an overgrown landscape

The survey encompasses several major Mayan sites, including Tikal and El Zotz.

“Everyone is seeing larger, denser sites. Everyone,” Thomas Garrison, assistant professor of anthropology at Ithaca College, said in a statement. “There’s a spectrum to it, for sure, but that’s a universal: everyone has missed settlement in their [previous] mapping.”

To conduct the survey, the researchers used an airplane-mounted device to send a constant pulse of laser light across a swath of terrain and take precise measurements of how long it takes the emitted breams to bounce off surfaces. The measurements were then translated into topographic data.

The laser pierces through the smallest gaps in the vegetation to record the lay of the land below with accuracy. The data is then tweaked to filter out trees and other vegetation, offering an unencumbered view of everything else on the surface.

The new technology will enable researchers to survey jungles across the globe. In the lowland of Guatemala, the dense canopy hinders other methods of aerial survey and thick undergrowth can conceal the relationships between known structures.

“In that kind of environment where you can’t see [a few feet in front of yourself], it’s very hard to piece that all together. “You have this idea that there’s some little stuff on the hills, but the LiDAR lets you see it in its totality.”

Overgrown landscape of the jungles of northern Guatemala have protected most of the remains of the Maya who once inhabited the area—yielding slowly to modern scientists hoping to learn more about the ancient civilization known for its sophisticated hieroglyphic script, art, architecture and mathematics.

The Maya civilization emerged about 3,000 years ago, reaching its peak during the Classic Period from about 250 to 900 AD.

According to Garrison, the newly revealed agricultural features likely supported the lowland Maya population during their centuries of civilization where the population estimates have now expanded from a few million to 10-to-20-million.

Defensive structures also suggest that warfare was far more prevalent than previously thought.

The discovery will be the subject of a new National Geographic documentary entitled “Lost Treasures of the Maya Snake King” that will premiere on Feb. 6 at 9 p.m. The documentary will follow a NatGeo explorer as he treks deep into the jungle to seek out a pyramid detected in the survey. The survey was the single largest ever conducted on Mesoamerican archaeology.

Garrison explained that the researchers would now use the LiDAR findings to discover more about the rise, peak and fall of the Maya civilization.

“That’s the challenge now. Now we have so much data,” Garrison said. “How do we handle it and how do we move forward with it?

“We’ve still got to get to those places, we’ve still got to check them out,” he added. “It’s difficult to convey how exciting this time is for us.”