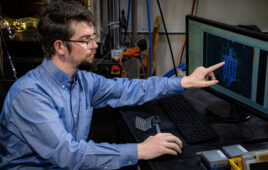

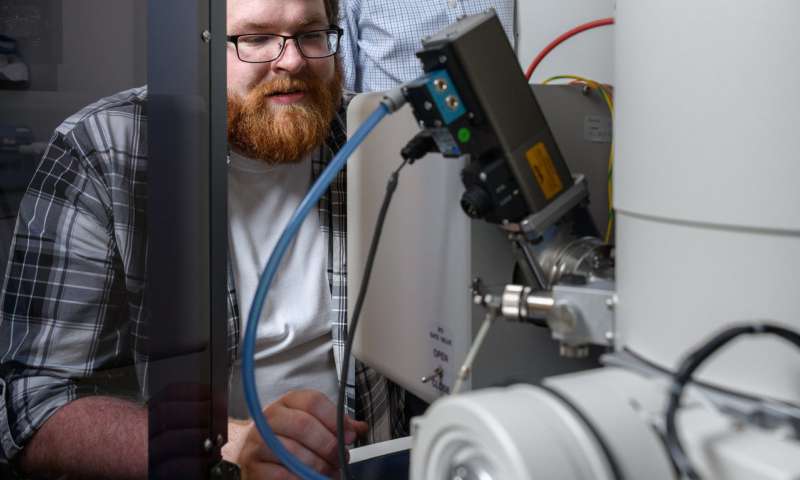

Matthew Boebinger, a graduate student at Georgia Tech, and Matthew McDowell, an assistant professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and the School of Materials Science and Engineering, used an electron microscope to observe chemical reactions in a battery-simulated environment. Credit: Rob Felt, Georgia Tech

From electric cars that travel hundreds of miles on a single charge to chainsaws as mighty as gas-powered versions, new products hit the market each year that take advantage of recent advances in battery technology.

But that growth has led to concerns that the world’s supply of lithium, the metal at the heart of many of the new rechargeable batteries, may eventually be depleted.

Now researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology have found new evidence suggesting that batteries based on sodium and potassium hold promise as a potential alternative to lithium-based batteries.

“One of the biggest obstacles for sodium- and potassium-ion batteries has been that they tend to decay and degrade faster and hold less energy than alternatives,” said Matthew McDowell, an assistant professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and the School of Materials Science and Engineering.

“But we’ve found that’s not always the case,” he added.

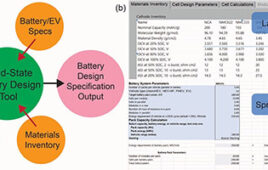

For the study, which was published June 19 in the journal Joule and was sponsored by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy, the research team looked at how three different ions—lithium, sodium, and potassium—reacted with particles of iron sulfide, also called pyrite and fool’s gold.

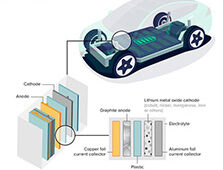

As batteries charge and discharge, ions are constantly reacting with and penetrating the particles that make up the battery electrode. This reaction process causes large volume changes in the electrode’s particles, often breaking them up into small pieces. Because sodium and potassium ions are larger than lithium, it’s traditionally been thought that they cause more significant degradation when reacting with particles.

In their experiments, the reactions that occur inside a battery were directly observed inside an electron microscope, with the iron sulfide particles playing the role of a battery electrode. The researchers found that iron sulfide was more stable during reaction with sodium and potassium than with lithium, indicating that such a battery based on sodium or potassium could have a much longer life than expected.

The difference between how the different ions reacted was stark visually. When exposed to lithium, iron sulfide particles appeared to almost explode under the electron microscope. On the contrary, the iron sulfide expanded like a balloon when exposed to the sodium and potassium.

“We saw a very robust reaction with no fracture—something that suggests that this material and other materials like it could be used in these novel batteries with greater stability over time,” said Matthew Boebinger, a graduate student at Georgia Tech.

The study also casts doubt on the notion that large volume changes that occur during the electrochemical reaction are always a precursor to particle fracture, which causes electrode failure leading to battery degradation.

The researchers suggested that one possible reason for the difference in how the different ions reacted with the iron sulfide is that the lithium was more likely to concentrate its reaction along the particle’s sharp cube-like edges, whereas the reaction with sodium and potassium was more diffuse along all of the surface of the iron sulfide particle. As a result, the iron sulfide particle when reacting with sodium and potassium developed a more oval shape with rounded edges.

While there’s still more work to be done, the new research findings could help scientists design battery systems that use these types of novel materials.

“Lithium batteries are still the most attractive right now because they have the most energy density—you can pack a lot of energy in that space,” McDowell said. “Sodium and potassium batteries at this point don’t have more density, but they are based on elements a thousand times more abundant in the earth’s crust than lithium. So they could be much cheaper in the future, which is important for large scale energy storage—backup power for homes or the energy grid of the future.”