Janice Wood University of Washington researchers re-created ancient projectile points to test their effectiveness. From left to right: stone, microblade and bone tips. Credit:

By recreating hunting tools from the Ice Age, researchers believe they can learn a lot about how early hunters adapted to technology.

A team of archaeologists from the University of Washington have recreated weapons used by post Ice Age Arctic hunter-gatherers some 14,000 years ago that may shed light on how early people advanced their own technology.

The project may also provide insight into human migration, ancient climates and the fate of certain animal species.

The researchers examined hunting weapons from the time of the earliest archaeological record in Alaska—between 10,000 and 14,000 years ago—when little is understood archaeologically and when different kinds of projectile points were used.

They then designed a pair of experiments to test the effectiveness of the different point types to reveal a new understanding about the technological choices people made during ancient times.

“The hunter-gatherers of 12,000 years ago were more sophisticated than we give them credit for,” Ben Fitzhugh, a UW professor of anthropology, said in a statement. “We haven’t thought of hunter-gatherers in the Pleistocene as having that kind of sophistication, but they clearly did for the things that they had to manage in their daily lives, such as hunting game.

“They had a very comprehensive understanding of different tools, and the best tools for different prey and shot conditions,” he added.

It is unknown whether different types of points were associated with only certain groups of people or whether the same groups used certain point types to specialize on particular kinds of game or hunting practices.

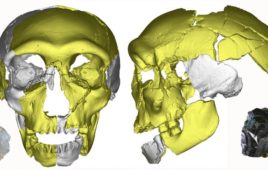

It is generally accepted that different point types were developed in Africa and Eurasia and brought to Alaska before the end of the Ice Age, including rudimentary points made of sharpened bone, antler or ivory; more intricate, flaked stone tips popularly familiar as “arrowheads”; and a composite point made of bone or antler with razor blade-like stone microblades embedded around the edges. .

The three tools were likely invented during different times but remained in use during the same period because each presumably has its own advantages.

The researchers traveled to Alaska and crafted 30 projectile points, 10 of each of the three tools. In an attempt to stay as true to the original materials and manufacturing processes, the researchers used poplar projectiles and birch tar as an adhesive to affix the points to the tips of the projectiles, as well as a maple recurve bow to shoot the arrows for greater control and precision.

Janice Wood, a recent UW anthropology graduate, tested how well each point could penetrate and damage blocks of ballistic gelatin and a fresh reindeer carcass.

During the field trial, the composite microblade points were more effective than simple stone or bone on smaller prey, showing the greatest versatility and ability to cause incapacitating damage no matter where they struck the animal’s body.

However, bone points penetrated deeply but created narrower wounds, suggesting their potential for puncturing and stunning larger prey, while the stone points could have cut wider wounds, especially on large prey (moose or bison), resulting in a quicker kill.

According to Wood, the findings show that hunters were sophisticated enough to recognize the best point to use and when.

“We have shown how each point has its own performance strengths,” she said. “It has to do with the animal itself; animals react differently to different wounds. And it would have been important to these nomadic hunters to bring the animal down efficiently. They were hunting for food.”