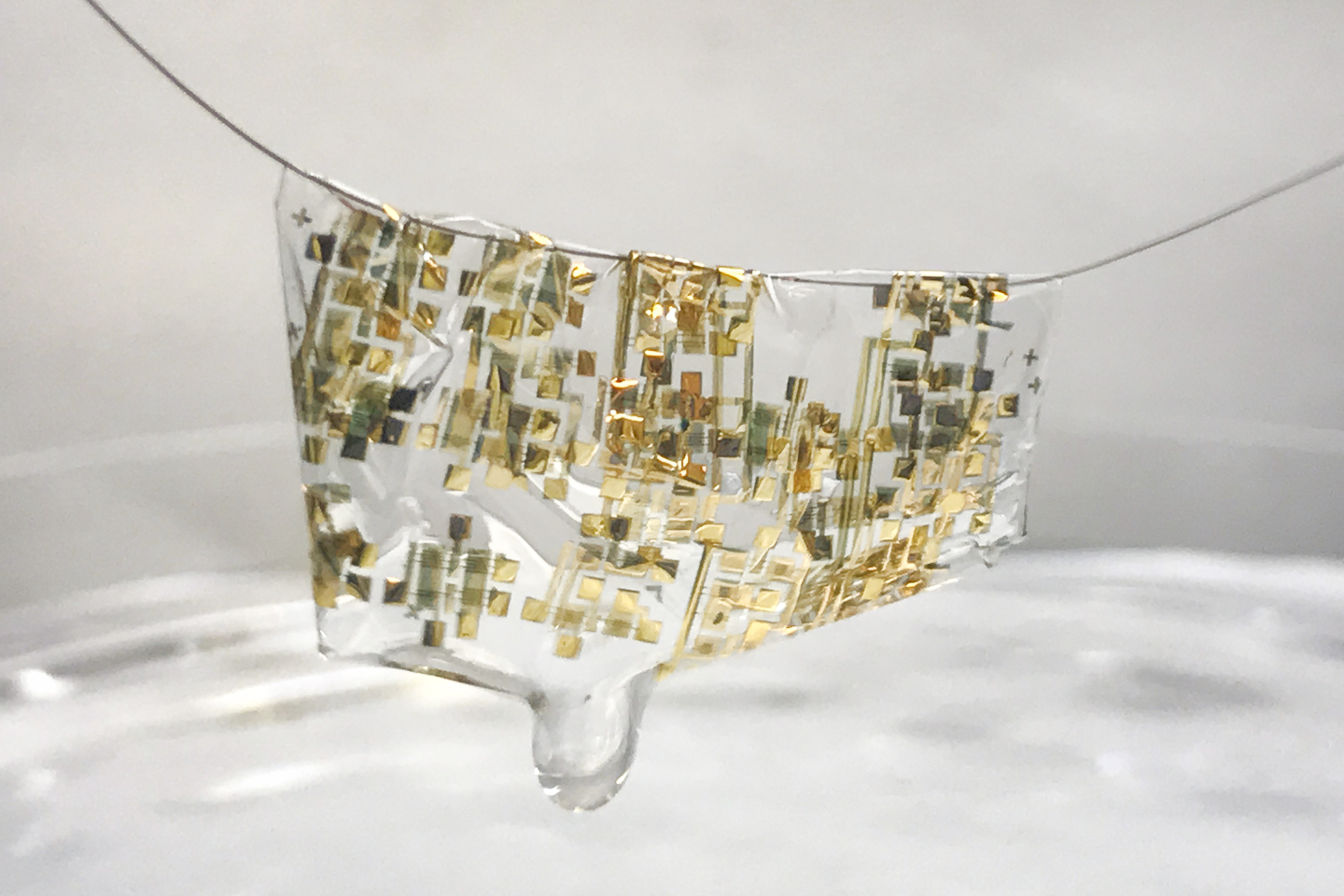

A newly developed flexible, biodegradable semiconductor developed by Stanford engineers shown on a human hair. Credit: Bao lab

To minimize the growing amount of electronic waste, researchers at Stanford University have developed a flexible, organic and biodegradable electronic device.

Stanford engineer Zhenan Bao led a team in developing the device, which can be used in a number of applications, including for wearable electronics and large-scale environmental surveys with sensor dusts.

“In my group, we have been trying to mimic the function of human skin to think about how to develop future electronic devices,” Bao said in a statement. “We have achieved the first two [flexible and self-healing], so the biodegradability was something we wanted to tackle.

“We have been trying to think how we can achieve both great electronic property but also have the biodegradability,” she added.

The device can easily degrade by just adding a weak acid like vinegar.

According to lead author Ting Lei, a postdoctoral fellow working with Bao, this is the first example of a semiconductive polymer that can decompose.

The team developed a degradable electronic circuit and a new biodegradable substrate material for mounting the electrical components that also supports the electrical components, flexing and molding to rough and smooth surfaces. The team also developed a new electronic component from iron and a substrate material from cellulose that attaches to the entire electronic component.

The entire electronic device can biodegrade into nontoxic components when it is no longer in use.

The researchers were able to tweak the chemical structure of a flexible material previously developed by Bao so that it would break apart under mild stressors, allowing the material to carry an electronic signal but break down without requiring extreme measures.

“We came up with an idea of making these molecules using a special type of chemical linkage that can retain the ability for the electron to smoothly transport along the molecule,” Bao said. “But also this chemical bond is sensitive to weak acid—even weaker than pure vinegar.”

According to Bao, one of the applications for this material is a wearable patch that a person could wear for a day or a week and then download the data.

“We envision these soft patches that are very thin and conformable to the skin that can measure blood pressure, glucose value, sweat content,” Bao said.

The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.