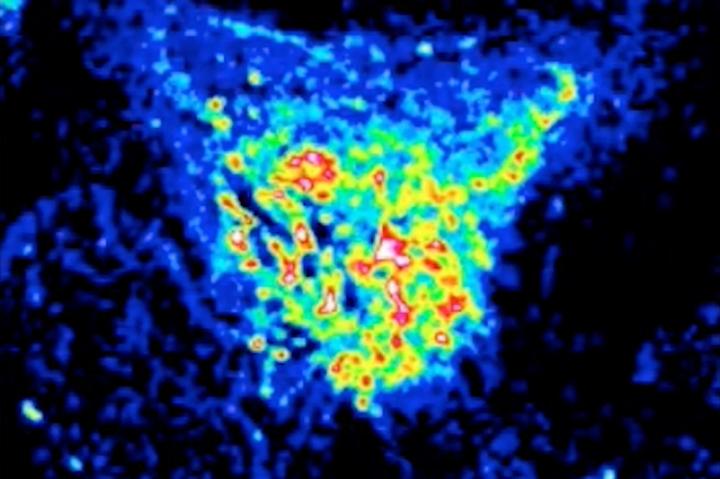

A Drosophila melanogaster male becomes aroused when recognizing a female of his own species, as evidenced by P1 neurons activating in his brain (right). Credit: Laboratory of Neurophysiology and Behavior at The Rockefeller University

For lovers throughout the animal kingdom, finding a suitable mate requires the right chemistry. Now, scientists at The Rockefeller University have been able to map an unexpected path in which evolution arranged for animals to choose the correct partner.

Working with fruit flies, the scientists probed how males manage to pick out members of their own species from the multitude of flies crowding around an overripe fruit. The answer, published this week in the journal Nature, upended long-held beliefs about how evolution works to ensure animals perpetuate their species.

Looking far and deep

Scientists have long assumed that animals don’t interbreed because evolution changed the peripheral parts of their nervous systems, including the sensory organs that detect and process pheromones–chemical substances that help identify others of the same species. Peripheral changes have been proposed to be essential to allow animals to develop species-specific behaviors, including mating, but it has not been possible to determine whether this was the main or only site of change in the nervous system.

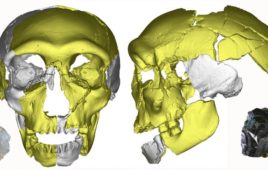

Vanessa Ruta, who heads the Laboratory of Neurophysiology and Behavior, set out with a team from her lab to discover what evolution had done to ensure that two closely related species of fruit flies–Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila simulans–stick to their own kind when mating. Using a host of state-of-the-art genetic and imaging tools, and inventing some new ones, the scientists tracked the electrochemical impulses starting at the sensory neurons in the male foreleg, which they use to “taste” pheromones, all the way to the brain’s central-processing center.

The differences between the species, they found, lies deep in the flies’ brains, in a small cluster of neurons that controls mating behavior. In fact, the peripheral nervous systems were unchanged, suggesting they play no part in the distinct mating choices of the different species, a finding Ruta hadn’t anticipated.

“I think scientists in the field have long thought the changes would most likely be localized to the periphery partially due to the fact that it is the simplest place to look,” she says. “People have not had the genetic tools available to really trace sensory signals as they propagate through brain circuitry.”

Fork in the road

D. melanogaster females produce a specific pheromone that acts as a powerful aphrodisiac and drives males to mate. Curiously, D. simulans males respond strongly to the same pheromone, but for them it is a powerful turnoff, stopping them from courting females of the wrong species.

The big question for Ruta’s team was where in the nervous system evolutionary changes had occurred that account for the flies’ opposite responses to the same pheromone.

In searching for the answer, Laura Seeholzer, a doctoral student in Ruta’s lab, used Crispr-Cas9 gene editing to determine that males of the two species detect the pheromone in the same way. The neuronal pathways also are identical as they travel toward the brain, she found. In both species, the path splits into two channels: One pathway forms a so-called excitatory interneuron that encourages mating, and the other an inhibitory interneuron to damp the urge.

The first sign of a functional difference between the fly species came when the scientists tested what goes on in a cluster of neurons known as P1 that controls courtship behavior. In one experiment, males of both species were allowed to touch a D. melanogaster female, tasting her pheromones.

The D. melanogaster males were suitably aroused, with their P1 neurons lighting up using functional imaging of brain activity. But for the D. simulans males, it was lights out.

Next, the team sought to artificially excite or inhibit sexual desire in the males by directly stimulating the P1 node. It was a tall-order experiment: While genetic tools are readily available to manipulate neurons in D. melanogaster, one of the most widely studied animal species, little research has been done on D. simulans, forcing Seeholzer and colleagues to devise new techniques to genetically label neurons of that species so they could examine their role in mating choices.

The result: Both excitatory and inhibitory pathways are present in both fly species. But it is the balance of their input to the P1 neurons that is responsible for the flies’ opposite reactions to the same pheromone, the research found. For D. simulans males, tasting pheromones of another species causes the inhibitory pathway to dominate, masking any impulse to mate.

“Seeing the different responses in the P1 neurons across species was the point where we thought, we’ve identified a site where evolutionary change has occurred” to keep the two species from interbreeding, Ruta says.

She hopes to expand the research to compare additional species of flies in an effort to uncover additional ways in which evolution may drive behavior. Until recently, such research was incredibly time consuming. But with new genetic tools, including Crispr-Cas9, it is now possible to compare neuronal circuits between species, she says.