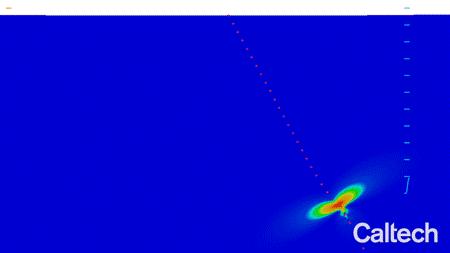

The model shows how the hanging wall (right) of a thrust fault can twist away from the foot wall (left) during an earthquake. Source: Harsha Bhat/ENS

It is a common trope in disaster movies: an earthquake strikes, causing the ground to rip open and swallow people and cars whole. The gaping earth might make for cinematic drama, but earthquake scientists have long held that it does not happen.

Except, it can, according to new experimental research from Caltech.

The work, appearing in the journal Natureon May 1, shows how the earth can split open — and then quickly close back up — during earthquakes along thrust faults.

Thrust faults have been the site of some of the world’s largest quakes, such as the 2011 Tohoku earthquake off the coast of Japan, which damaged the Fukushima nuclear power plant. They occur in weak areas of the earth’s crust where one slab of rock compresses against another, sliding up and over it during an earthquake.

A team of engineers and scientists from Caltech and École normale supérieure (ENS) in Paris have discovered that fast ruptures propagating up toward the earth’s surface along a thrust fault can cause one side of a fault to twist away from the other, opening up a gap of up to a few meters that then snaps shut.

Thrust fault earthquakes generally occur when two slabs of rock press against one another, and pressure overcomes the friction holding them in place. It has long been assumed that, at shallow depths the plates would just slide against one another for a short distance, without opening.

However, researchers investigating the Tohoku earthquake found that not only did the fault slip at shallow depths, it did so by up to 50 meters in some places. That huge motion, which occurred just offshore, triggered a tsunami that caused damage to facilities along the coast of Japan, including at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.

In the Nature paper, the team hypothesizes that the Tohoku earthquake rupture propagated up the fault and–once it neared the surface — caused one slab of rock to twist away from another, opening a gap and momentarily removing any friction between the two walls. This allowed the fault to slip 50 meters.

That opening of the fault was supposed to be impossible.

“This is actually built into most computer models of earthquakes right now. The models have been programed in a way that dictates that the walls of the fault cannot separate from one another,” says Ares Rosakis, Theodore von Kármán Professor of Aeronautics and Mechanical Engineering at Caltech and one of the senior authors of the Nature paper. “The findings demonstrate the value of experimentation and observation. Computer models can only be as realistic as their built-in assumptions allow them to be.”

The international team discovered the twisting phenomenon by simulating an earthquake in a Caltech facility that has been unofficially dubbed the “Seismological Wind Tunnel.” The facility started as a collaboration between Rosakis, an engineer studying how materials fail, and Hiroo Kanamori, a seismologist exploring the physics of earthquakes and a coauthor of the Nature study. “The Caltech research environment helped us a great deal to have close collaboration across different scientific disciplines,” Kanamori said. “We seismologists have benefited a great deal from collaboration with Professor Rosakis’s group, because it is often very difficult to perform experiments to test our ideas in seismology.”

At the facility, researchers use advanced high-speed optical diagnostics to study how earthquake ruptures occur. To simulate a thrust fault earthquake in the lab, the researchers first cut in half a transparent block of plastic that has mechanical properties similar to that of rock. They then put the broken pieces back together under pressure, simulating the tectonic load of a fault line. Next, they place a small nickel-chromium wire fuse at the location where they want the epicenter of the quake to be. When they set off the fuse, the friction at the fuse’s location is reduced, allowing a very fast rupture to propagate up the miniature fault. The material is photoelastic, meaning that it visually shows — through light interference as it travels in the clear material — the propagation of stress waves. The simulated quake is recorded using high-speed cameras and the resulting motion is captured by laser velocimeters (particle speed sensors).

“This is a great example of collaboration between seismologists, tectonisists and engineers. And not to put too fine a point on it, US/French collaboration,” says Harsha Bhat, coauthor of the paper and a research scientist at ENS. Bhat was previously a postdoctoral researcher at Caltech.

The team was surprised to see that, as the rupture hit the surface, the fault twisted open and then snapped shut. Subsequent computer simulations–with models that were modified to remove the artificial rules against the fault opening–confirmed what the team observed experimentally: one slab can twist violently away from the other. This can happen both on land and on underwater thrust faults, meaning that this mechanism has the potential to change our understanding of how tsunamis are generated.