It is increasingly challenging to plan R&D in a way that will keep the company ahead of the demands of consumers and competitors, especially within durable goods and materials science companies.

Some site an issue with “R&D lag”—the inability of R&D teams to make new materials that can meet consumer demands. While R&D teams don’t always agree that they lag behind market requirements, there is a common view that product managers must give R&D planners much earlier and better cues about what’s coming in the market. They need to know what will be needed and when, if their company is to meet market needs. Otherwise the R&D team has to forecast these needs themselves.

On the other hand, market facing teams—such as product managers and marketing staff—often feel that they do provide R&D teams with the information they need. R&D planners often reply in return that what they get is “too little and too late,” since they often need far longer to identify or create new materials than the 12 to 18 month “forecast window” they get from product and marketing managers.

Understanding the disconnect

R&D planners want more clarity on three types of information: Emerging customer needs, new technologies, and competitors’ plans for meeting customer needs using new technologies. They want to know:

–What attributes customers will likely want in their products, and when they will need them—in time to develop materials that suit the need (often over a much longer time frame than they’re given).

-What technologies are “just over the horizon” or newly emerging, that might be commercialized to meet customer needs.

-What competitors are doing to meet the need, and what technologies they are using to do this.

For customer needs and competitor intelligence, R&D teams often look to their market facing teams to help plan R&D activities. For technology forecasting, R&D leaders often indicate they feel they have a direct mandate to do this work themselves—but that they lack a process to do that forecasting, beyond simple web searches and searches of patent applications.

Multiple conversations with market, product, and R&D planners, left us with these questions:

-Do many companies believe that R&D production lags behind market demand?

– What forces make it hard for R&D planners to clearly see what’s needed? Why can’t they get the information they need from marketing and product management?

-Do companies really expect their R&D to be able to anticipate market changes?

-In those companies doing a reasonable job of getting R&D planners the information they need, how are they doing it?

To answer these questions, we launched a project to interview personnel at ten different companies that were engaged in market, product, or R&D planning. (Most of our interviews were on the R&D side.) We conducted over 50 in-depth interviews. Our study’s preliminary findings show the need for a further quantitative study, engaging many more companies—but they also provide some interesting initial insights. These insights are captured below.

What makes R&D planning (increasingly) so hard?

An increasing pace of change means R&D teams need better abilities to forecast change. Companies that rely on technology for competitive advantage face continual stress as competitors acquire and apply new technologies that could outpace (or replace) them. Ray Kurzweil proposed in his 2001 essay “The Law of Accelerating Returns,” that the pace of technological change is exponential, doubling (at the time of his writing) every 10 years, as successive innovators create “ever more powerful technologies using the tools from the previous round of innovation.” (Ray Kurzweil (2001)).

For consumers, this acceleration of change may be most visible in consumer electronics. Smart phones (and their twin, personal tablets) are an example. MIT Technology Review noted in 2012 that smart phones may be “spreading faster” than any technology in human history. But mobile devices are not the only area where consumers expect to see rapid change.

The dark side of this astounding growth is that accelerating change in consumer electronics and mobile applications may be creating additional problems for durables goods manufacturers, as customers come to expect the same pace of change in products everywhere.

Rapid improvements in consumer technology create expectations in other fields

As new technology changes what consumers can get from phones, tablets, and mobile apps, consumers expect faster changes in other areas—such as automobiles and household appliances. But many durable goods manufacturers may face longer development times and higher costs than those normally seen in information technology.

More than one R&D leader described the way that consumer expectations for consumer electronics has affected expectations for durable goods, this way:

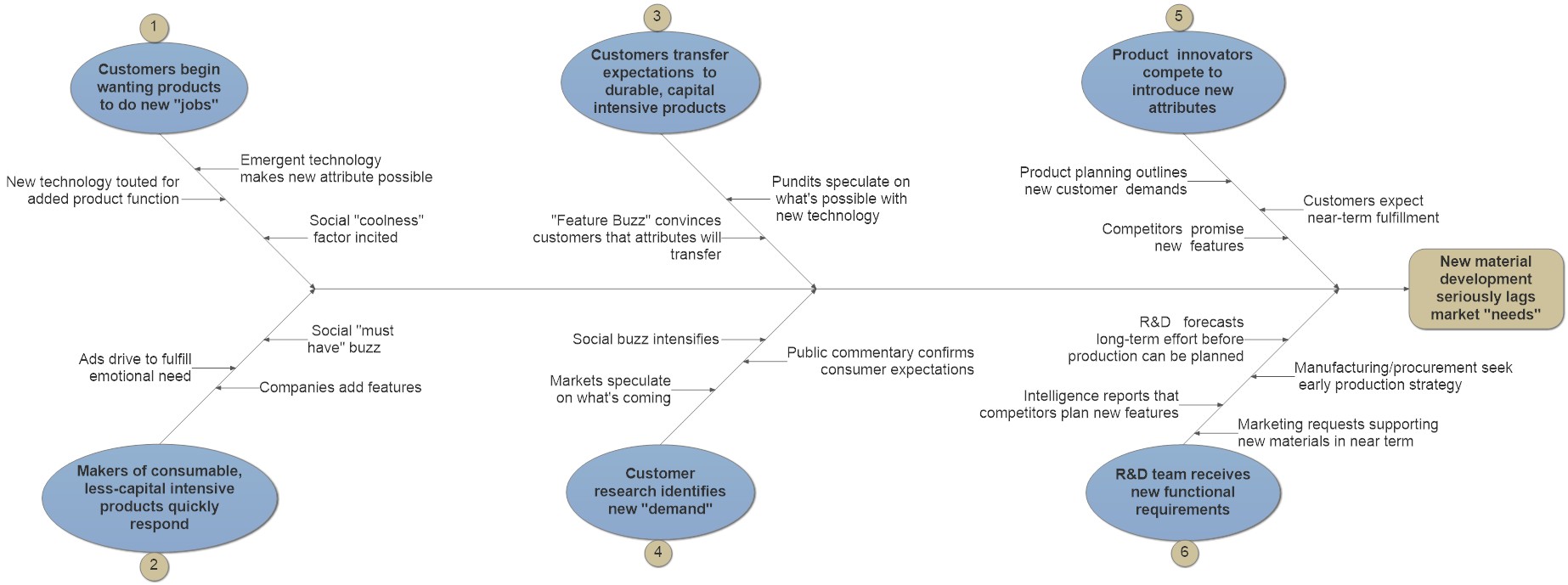

-Advances in consumer electronics are accelerating; consumers want the “next hot thing”

-Change watchers theorize about how new technologies could open up brand new applications

-Social media picks up on the possibilities, and consumers discover a new “need”

-Marketers seek the fastest path to an application, and companies compete to create it

The diagram below outlines this process as it was explained to us.

Market-facing teams may not be able to deliver to R&D planners the information that they need

Many companies expect R&D teams to lead in technology forecasting, given R&D’s technology expertise. But the market and product strategy often can’t seem to deliver intelligence that R&D teams need about future customer needs or competitor technology moves. This may be because, as an R&D executive at one company told us, “marketing and sales functions are so occupied in today’s market share battles that they can’t look further than what customers will want in the near-term, so they miss what might emerge a few years later.”

If market researchers and product planners in their company are focused more on the near term, R&D has to do its own long-range forecasting if they need a long-range forecast about not only technology, but also customer needs and competitor moves.

Many R&D leaders said their strategic marketing departments worked to anticipate trends 12 to 18 months out—but that R&D planners need a forecast going ten to twelve years out in order to create new materials for future products.

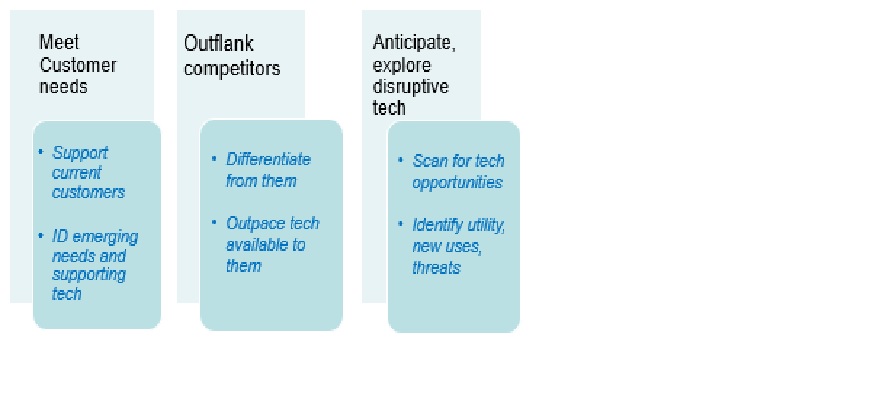

Executives in many technology-dependent companies see R&D in a market surveillance role

Our interviews revealed that many high-level corporate executives seem to expect R&D to fulfill the three basic functions shown in the graphic below.

This “clear foresight” in many cases seems to require that R&D planners have access to all three major streams of information about future trends—customer needs, emerging technologies, and competitor applications of technology.

What are companies doing to help get the intelligence they need for R&D planning?

We’ve captured key findings from our interviews with three small and seven large durable goods and materials science companies below.

Again, these findings could be further validated through more extensive research beyond our initial 50 interviews.

Not every company we identified does these things: Nearly all of them do some of these things. While we can’t share the names of the companies involved, the large companies were global enterprises, with R&D teams numbering in the hundreds.

Common practices

Here are the best of the common practices we found among companies where executives felt they had effectively addressed the issue of equipping the R&D team with better information and “longer-range radar” for R&D planning. These companies:

Train and help the R&D teams to directly gather intelligence about emerging customer needs: The R&D team must get directly involved in customer research. In some firms we interviewed, R&D team members accompanied market facing personnel to interview customers about unmet needs. “R&D tends to ask about more long-term needs” one respondent said, “while marketing is looking for customer needs that will drive next year’s sales.”

Gather conference intelligence in a disciplined way: Every company in this study relies heavily on technical and scientific conferences and tradeshows for insights into what is coming. Two companies provide advance training to their personnel who will be attending these meetings. This training includes work on ethics and honesty— while still conducting conversations that yield a maximum benefit. Very importantly, conference attendees need a way to share the intelligence they learned with all those who need it.

Often use scenario generation to look “over the horizon,” and identify what they need to learn: To many in R&D, periodically generating future scenarios is key to making sense of market signals they have detected. Scenario generation and scenario planning are the most commonly used techniques these companies use to look “over the horizon” to detect emerging market needs and technical or competitor trends. Three companies use this technique regularly, usually bringing together both technical and market-facing personnel (and often outside experts) to consider potential future developments.

Scenario generation is also often an essential step in the process of listing and ranking intelligence priorities—determining what intelligence is needed, and why—and how that information, if found, could be expected to inform R&D planning.

Work in cross-regional and inter-echelon teams to share market intelligence findings: A number of companies we interviewed ensure that market-facing teams and technical teams meet often in formal and ad-hoc ways to ensure they fully share what each is looking for in the market (new technologies; competitor activities; customer need details), and what they are each finding.

As intelligence is found, it is shared and discussed in face-to-face and phone meetings, and in online forums. As one executive pointed out, “most of our aha’s come from talking through” findings, rather than simply reading about them.

Less common but highly effective practices included the following.

Encourage their R&D team to gather competitor intelligence: In many technology-dependent enterprises in our study, the R&D team handles competitive intelligence functions within R&D. Companies in life sciences are best at this.

Perhaps this shouldn’t be surprising. According to a 2008 study, in the pharmaceutical industry, the greatest proportion of Competitive Intelligence (CI) practice in the pharmaceutical industry is located within the R&D function (Halliday et al 1992).

In one large company, a team of researchers who have technical background and training in market and competitive intelligence research, work to scan adjacent industries and current competitors for both threats and opportunities that the R&D team might address.

Create and use prioritized lists of what intelligence is needed: This is often an enterprise-wide listing of what information is needed most. Key Intelligence Topics (KITs) are created through a process that could start with scenarios where R&D believes the market is going; what customers will need; and competitors might do—and what technologies might be available at a future point.

This activity includes an exercise that points up where assumptions fall short, and ends with a plan to gather intelligence through conference contacts, work with universities, or collaboration with other peers. These efforts also help set R&D priorities and vet R&D projects for initial funding or continuance.

Use human sources to obtain insights into market trends: Companies that excel in developing long-range market forecasts with confidence all seem to gather intelligence directly from people. They don’t rely on published data for their principal insights. Published information can tell them what has happened, but only people can tell them what is planned for the future.

In conclusion

R&D organizations are increasingly under pressure to provide their companies with a technical competitive advantage. This can be done much more effectively when R&D plans take into account long-range intelligence about what customers will likely want; what technology may be able to deliver, and what technologies competitors are most likely to employ.

To do this, R&D teams must intensely collaborate with market facing organizations—but also must be trained, and directly involved in the collection of some aspects of intelligence, especially customer intelligence. This can take time.

All three types of intelligence—customer, technical, and competitor—are essential for scenarios of future technical needs (and future plans) to be reliable.

About the authors: Kent and Nancy Potter are co-founders of Bennion Group, a consultancy that focuses on applied intelligence to accelerate innovation and growth. Kent is also an adjunct professor at Utah Valley University