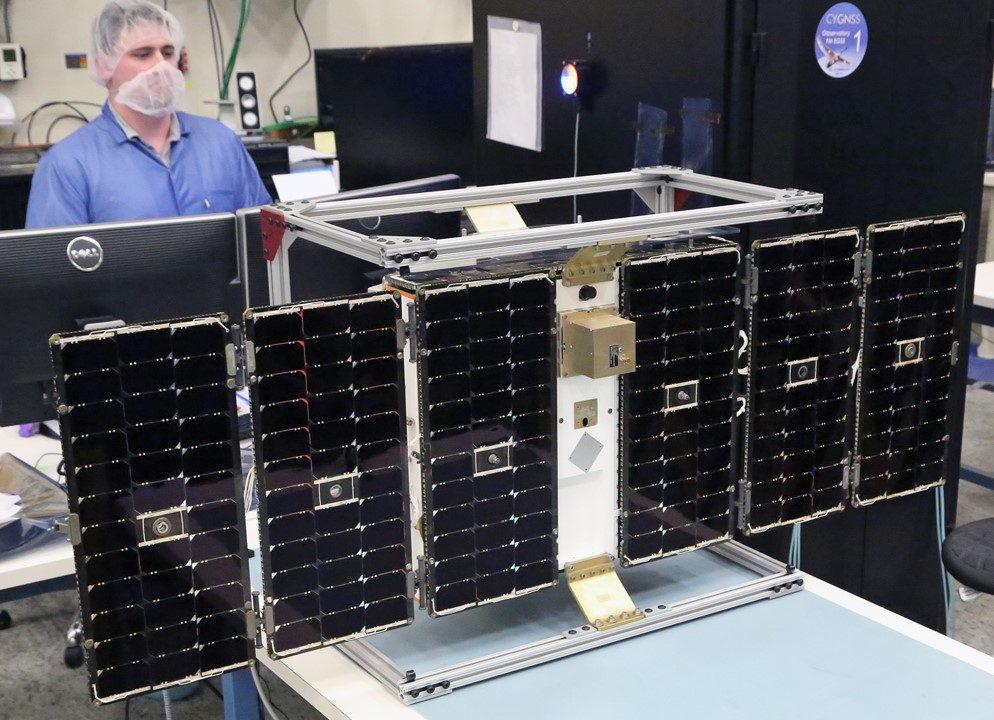

One of the eight microsatellites in the CYGNSS constellation under construction. The mission is set to launch in December to collect data to improve hurricane intensity forecasts. Image: University of Michigan

Beginning this month, NASA is launching a suite of six next-generation, Earth-observing small satellite missions to demonstrate innovative new approaches for studying our changing planet.

These small satellites range in size from a loaf of bread to a small washing machine and weigh from a few to 400 pounds. Their small size keeps development and launch costs down as they often hitch a ride to space as a “secondary payload” on another mission’s rocket — providing an economical avenue for testing new technologies and conducting science.

“NASA is increasingly using small satellites to tackle important science problems across our mission portfolio,” says Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. “They also give us the opportunity to test new technological innovations in space and broaden the involvement of students and researchers to get hands-on experience with space systems.”

Small-satellite technology has led to innovations in how scientists approach Earth observations from space. These new missions, five of which are scheduled to launch during the next several months, will debut new methods to measure hurricanes, Earth’s energy budget, aerosols, and weather.

“NASA is expanding small satellite technologies and using low-cost, small satellites, miniaturized instruments, and robust constellations to advance Earth science and provide societal benefit through applications,” says Michael Freilich, director of NASA’s Earth Science Division in Washington.

Scheduled to launch this month, RAVAN, the Radiometer Assessment using Vertically Aligned Nanotubes, is a CubeSat that will demonstrate new technology for detecting slight changes in Earth’s energy budget at the top of the atmosphere — essential measurements for understanding greenhouse gas effects on climate. RAVAN is led by Bill Swartz at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md.

In spring 2017, two CubeSats are scheduled to launch to the International Space Station for a detailed look at clouds. Data from the satellites will help improve scientists’ ability to study and understand clouds and their role in climate and weather.

IceCube, developed by Dong Wu at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, will use a new, miniature, high-frequency microwave radiometer to measure cloud ice. HARP, the Hyper-Angular Rainbow Polarimeter, developed by Vanderlei Martins at the University of Maryland Baltimore County in Baltimore, will measure airborne particles and the distribution of cloud droplet sizes with a new method that looks at a target from multiple perspectives.

In early 2017, MiRaTA — the Microwave Radiometer Technology Acceleration mission – is scheduled to launch into space with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Joint Polar Satellite System-1. MiRaTA packs many of the capabilities of a large weather satellite into a spacecraft the size of a shoebox, according to principal investigator Kerri Cahoy from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. MiRaTA’s miniature sensors will collect data on temperature, water vapor and cloud ice that can be used in weather forecasting and storm tracking.

The RAVAN, HARP, IceCube, and MiRaTA CubeSat missions are funded and managed by NASA’s Earth Science Technology Office (ESTO) in the Earth Science Division. ESTO supports technologists at NASA centers, industry, and academia to develop and refine new methods for observing Earth from space, from information systems to new components and instruments.

“The affordability and rapid build times of these CubeSat projects allow for more risk to be taken, and the more risk we take now the more capable and reliable the instruments will be in the future,” says Pamela Millar, ESTO flight validation lead. “These small satellites are changing the way we think about making instruments and measurements. The cube has inspired us to think more outside the box.”

NASA’s early investment in these new Earth-observing technologies has matured to produce two robust science missions, the first of which is set to launch in December.

CYGNSS — the Cyclone, Global Navigation Satellite System — will be NASA’s first Earth science small satellite constellation. Eight identical satellites will fly in formation to measure wind intensity over the ocean, providing new insights into tropical cyclones. Its novel approach uses reflections from GPS signals off the ocean surface to monitor surface winds and air-sea interactions in rapidly evolving cyclones, hurricanes, and typhoons throughout the tropics. CYGNSS, led by Chris Ruf at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, is targeted to launch on Dec. 12 from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

Earlier this year NASA announced the start of a new mission to study the insides of hurricanes with a constellation of 12 CubeSats. TROPICS — the Time-Resolved Observations of Precipitation structure and storm Intensity with a Constellation of Smallsats — will use radiometer instruments based on the MiRaTA CubeSat that will make frequent measurements of temperature and water vapor profiles throughout the life cycle of individual storms. William Blackwell at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lincoln Laboratory in Lexington leads the mission.

CYGNSS and TROPICS both benefited from early ESTO technology investments. These Earth Venture missions are small, targeted science investigations that complement NASA’s larger Earth research missions. The rapidly developed, cost-constrained Earth Venture projects are competitively selected and funded by NASA’s Earth System Science Pathfinder program within the Earth Science Division.

Small spacecraft and satellites are helping NASA advance scientific and human exploration, reduce the cost of new space missions, and expand access to space. Through technological innovation, small satellites enable entirely new architectures for a wide range of activities in space with the potential for exponential jumps in transformative science.

Source: NASA