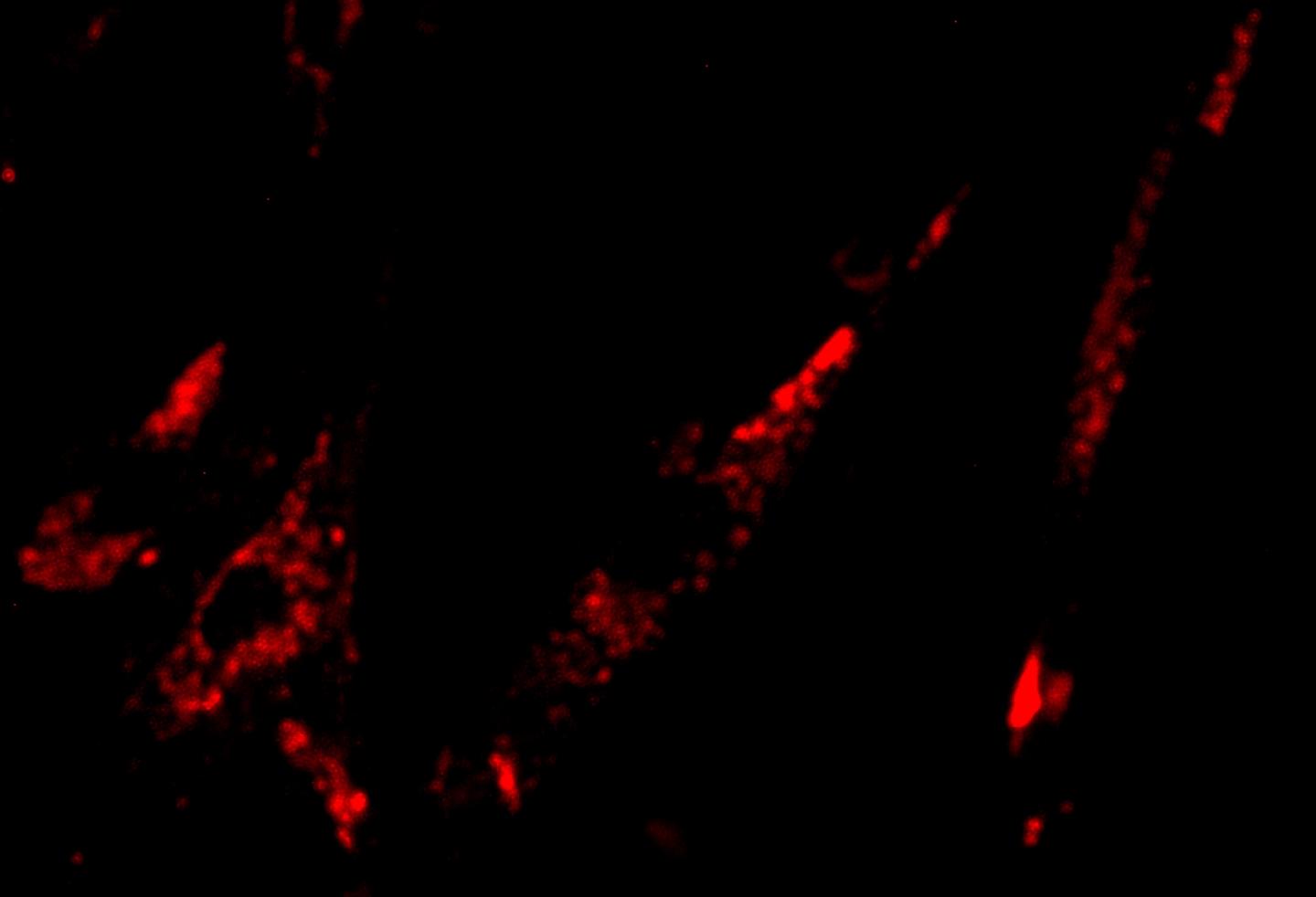

By illuminating the enzyme beta-galactosidase in a cell culture, Michigan Tech chemists hope to make it easier to leave more healthy tissue behind in cancer surgery. Source: Haiying Liu, Michigan Tech

What if you could plaster cancer cells with glowing “Here We Are” signs, so surgeons could be confident that they’d removed every last speck of a tumor? That’s what Haiying Liu has in mind for his new fluorescent probe.

“Doctors need to pinpoint cancer tissue, but that can be hard,” said Liu, a chemistry professor at Michigan Technological University. Test-tube cancer antibodies coupled with special enzymes have been used to highlight malignancies during surgery, since they bind to tumor cells, but they have a drawback.

“They are colorless,” he said. “You can label something, but if you can’t see it, that’s a problem.” Now Liu has developed a probe that could cling to those enzyme-coated antibodies and make them glow under fluorescent light. The journal Analytic Chimica Acta recently published the research.

The fluorescent probe has some appealing medical properties:

- It fluoresces in near-infrared, which can penetrate deep tissues, a property that would allow surgeons to detect malignancies buried in healthy tissue.

- It would result in less “background noise” for surgeons, since other fluorescent tissues typically glow green or blue.

- It is virtually nontoxic at low concentrations.

- It responds quickly to the enzyme at ultra-low concentrations.

- Its fluorescence is stable and long lasting, so it could shine through hours-long cancer operations.

The probe bonds to an enzyme that has a long track record in medical science. Beta-galactosidase has been widely used to label a variety of antibodies that have been used in multiple medical applications, including cancer surgery. “If we could make beta-galactosidase glow brightly during surgery, it could play a major role in improving outcomes,” Liu said.

In the new paper, Liu’s team showed how the probe bonds to beta-galactocidase in a solution of living cells. In the future, they would like to collaborate with medical researchers to refine their system, incorporating enzyme-labelled cancer antibodies and developing it as a guide for surgeons.

“Doctors want to remove all the cancer, but they also don’t want to cut too much,” Liu said. “We want to make their job a little easier.”