Kayla Wiles, Purdue University

Purdue engineers have figured out a way to tackle plastic landfills while also improving batteries — by putting ink-free plastic soaked in sulfur-containing solvent into a microwave, and then into batteries as a carbon scaffold.

Lithium-sulfur batteries have been hailed as the next generation of batteries to replace the current lithium ion variety. Lithium-sulfur batteries are cheaper and more energy-dense than lithium ions, which would be important characteristics in everything from electric vehicles to laptops.

But the knock on lithium-sulfur batteries to this point is that they don’t last as long, being usable for about 100 charging cycles.

Purdue researchers have found a way to increase the life span in a process that has the added bonus of being a convenient way to recycle plastic. Their process, which was recently published in ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, shows that putting sulfur-soaked plastic in a microwave, including transparent plastic bags, transforms the material into the ideal substance for increasing the life span of the forthcoming batteries to more than 200 charging-discharging cycles.

“No matter how many times you recycle plastic, that plastic stays on the earth,” says Vilas Pol, associate professor in Purdue’s School of Chemical Engineering. “We’ve been thinking of ways to get rid of it for a long time, and this is a way to at least add value.”

The need to reduce landfills runs parallel to making lithium-sulfur batteries good enough for commercial use.

“Because lithium-sulfur batteries are getting more popular, we want to get a longer life sucked out of them,” Pol says.

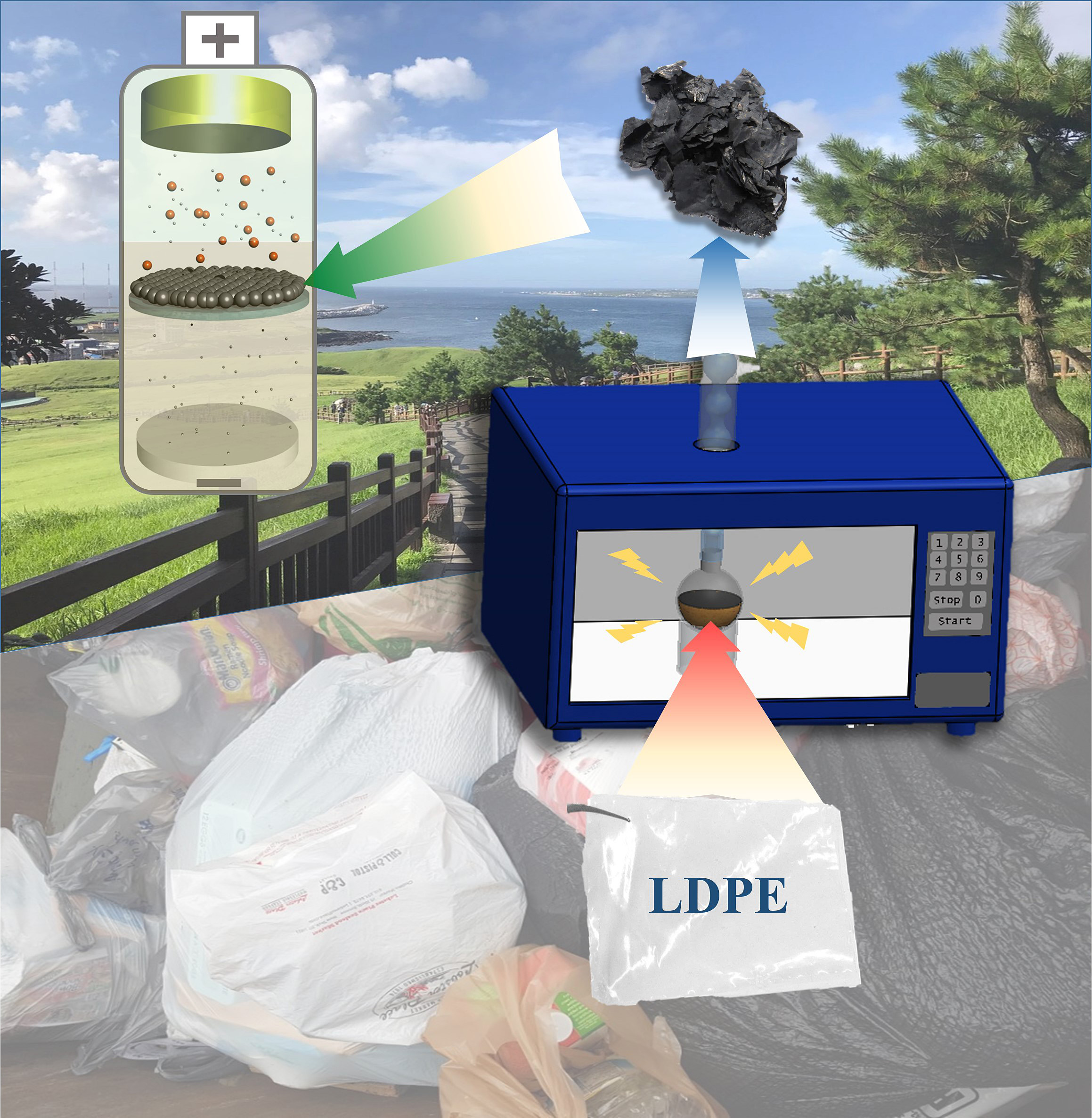

Researchers have discovered that soaking low density plastic in a sulfur-containing solvent, putting it into a microwave and transforming it into a carbon scaffold makes lithium-sulfur batteries last longer and retain elevated capacity. Image: Purdue University image/Patrick Kim

Low-density polyethylene plastic, which is used for packaging and comprises a big portion of plastic waste, helps address a long-standing issue with lithium-sulfur batteries — a phenomenon called the polysulfide shuttling effect that limits how long a battery can last between charges.

Lithium-sulfur batteries, as their name suggests, have a lithium and a sulfur. When a current is applied, lithium ions migrate to the sulfur and a chemical reaction takes place to produce lithium sulfide. The byproduct of this reaction, polysulfide, tend to cross back over to the lithium side and prevent the migration of lithium ions to sulfur. This decreases the charge capacity of a battery as well as life span.

“The easiest way to block polysulfide is to place a physical barrier between lithium and sulfur,” says Patrick Kim, a Purdue postdoc research associate in chemical engineering.

Previous studies had attempted making this barrier out of biomass, such as banana peels and pistachio shells, because the pores in biomass-derived carbon had the potential to catch polysulfide.

“Every material has its own benefit, but biomass is good to keep and can be used for other purposes,” Pol says. “Waste plastic is really valueless and burdensome material.”

Instead, researchers thought of how plastic might be incorporated into a carbon scaffold to suppress polysulfide shuttling in a battery. Past research had shown that low-density polyethylene plastic yields carbon when combined with sulfonated groups.

The researchers soaked a plastic bag into sulfur-containing solvent and put it in a microwave to cheaply provide the quick boost in temperature needed for transformation into low-density polyethylene. The heat promoted the sulfonation and carbonization of the plastic and induced a higher density of pores for catching polysulfide. The low-density polyethylene plastic could then be made into a carbon scaffold to divide the lithium and sulfur halves of a battery coin cell.

“The plastic-derived carbon from this process includes a sulfonate group with a negative charge, which is also what polysulfide has,” Kim says. Sulfonated low-density polyethylene made into a carbon scaffold, therefore, suppressed polysulfide by having a similar chemical structure.

“This is the first step for improving the capacity retention of the battery,” Pol says. “The next step is fabricating a bigger-sized battery utilizing this concept.”

This research was funded by the Naval Enterprise Partnership Teaming with Universities for National Excellence Center for Power and Energy Research at Purdue.

Source: Purdue University