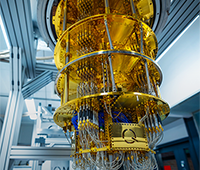

Today’s personal computer (PC) is far more powerful than its predecessor from previous generations and, unlike PCs of the past, can handle numerous operations at once, but it is no match for a supercomputer. The supercomputer is like asking 100 million PCs to work on a complex problem. Supercomputers have many processors that split problems into chunks, with each processor working on a different piece of the problem and all the processors working together at the same time.

Today’s personal computer (PC) is far more powerful than its predecessor from previous generations and, unlike PCs of the past, can handle numerous operations at once, but it is no match for a supercomputer. The supercomputer is like asking 100 million PCs to work on a complex problem. Supercomputers have many processors that split problems into chunks, with each processor working on a different piece of the problem and all the processors working together at the same time.

The performance of a supercomputer is commonly measured in floating-point operations per second (FLOPS) instead of million instructions per second (MIPS). Since 2017, there are supercomputers which can perform over 1017 FLOPS (a hundred quadrillion FLOPS, 100 petaFLOPS or 100 PFLOPS). Since November 2017, all of the world’s fastest 500 supercomputers run Linux-based operating systems. Additional research is being conducted in the United States, the European Union, Taiwan, Japan and China to build faster, more powerful and technologically superior exascale supercomputers.

Supercomputers are used to model and simulate complex, dynamic systems that would be too expensive, impractical or impossible to physically demonstrate, for example modeling the Earth’s climate. Supercomputers are changing the way scientists explore the evolution of our universe, biological systems, weather forecasting and even renewable energy.

In 2018 Oak Ridge National Laboratory unveiled Summit as the world’s most powerful and smartest scientific supercomputer. Developed by IBM for use at ORNL, it has a peak performance of 200,000 trillion calculations per second — or 200 petaflops. It was overtaken in ranking last year when Japan released the Fugaku, which boasts nearly 7.3 million cores and a speed of 415.5 petaFLOPS. Both Summit and Fugaku are used to address high-priority social and scientific issues. Both contributed to COVID-19 research.

Tell Us What You Think!