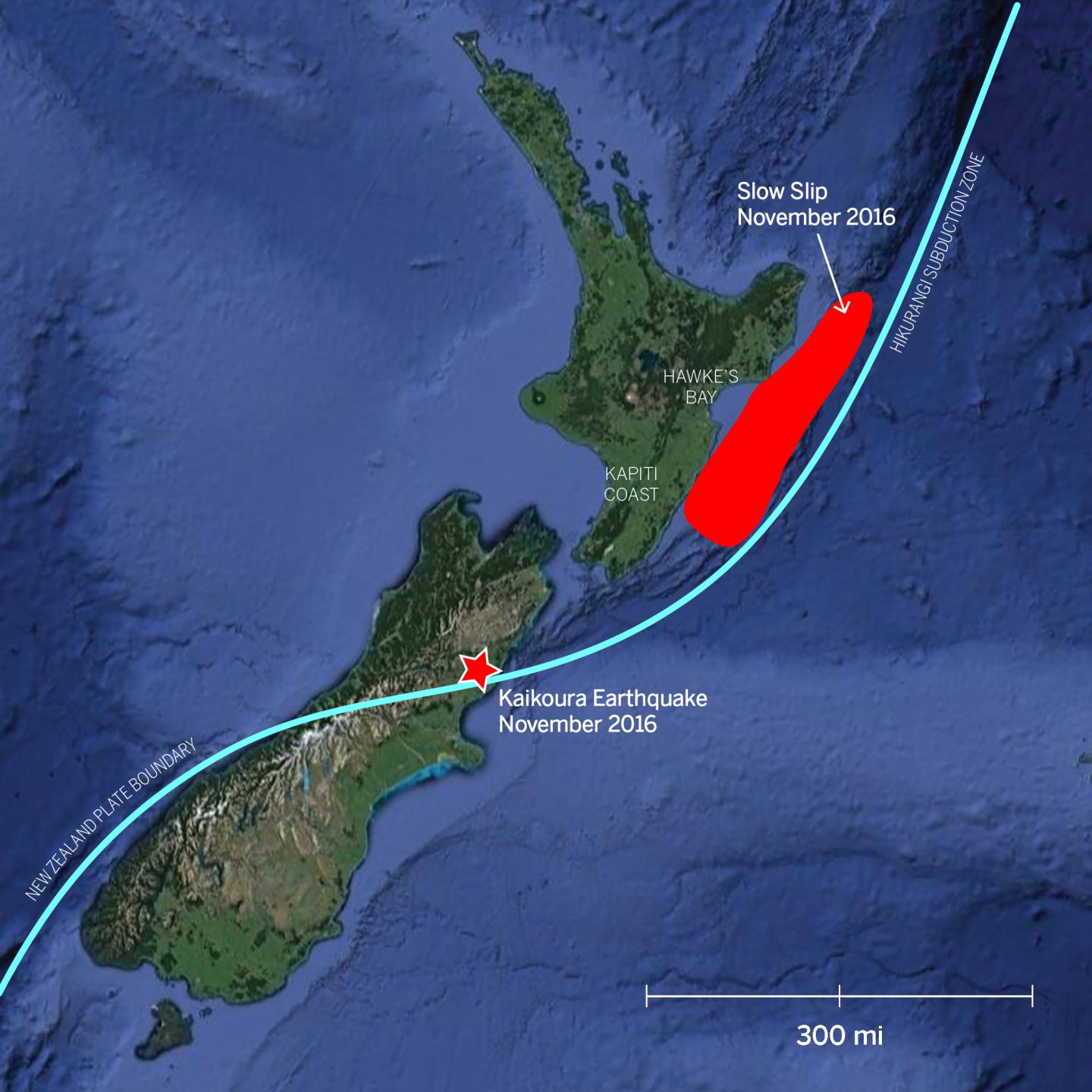

The 7.8 magnitude Kaik?ura earthquake (marked by a red star) triggered a slow slip event (marked by red area) on New Zealand’s North Island. The slow slip spanned an area comparable to the state of New Jersey. Both events occurred along a subduction zone, an area where a tectonic plate dives or “subducts” beneath an adjacent tectonic plate. This type of fault is responsible for causing some of the world’s most powerful earthquakes. Source:

Slow slip events, a type of slow motion earthquake that occurs over days to weeks, are thought to be capable of triggering larger, potentially damaging earthquakes. In a new study led by The University of Texas at Austin, scientists have documented the first clear-cut instance of the reverse–a massive earthquake immediately triggering a series of large slow slip events.

Some of the slow slip events occurred as far away as 300 miles from the earthquake’s epicenter. The study of new linkages between the two types of seismic activity, published in Nature Geoscience on Sept. 11, may help promote better understanding of earthquake hazard posed by subduction zones, a type of fault responsible for some of the world’s most powerful earthquakes.

“This is probably the clearest example worldwide of long-distance, large-scale slow slip triggering,” said lead author Laura Wallace, a research scientist at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG). She also holds a joint position at GNS Science, a New Zealand research organization that studies natural hazards and resources.

Co-authors include other GNS scientists, as well as scientists from Georgia Tech and the University of Missouri. UTIG is a research unit of the UT Jackson School of Geosciences.

In November 2016, the second largest quake ever recorded in New Zealand — the 7.8 magnitude Kaik?ura quake — hit the country’s South Island. A GPS network operated by GeoNet, a partnership between GNS Science and the New Zealand Earthquake Commission, detected slow slip events hundreds of miles away beneath the North Island. The events occurred along the shallow part of the Hikurangi subduction zone that runs along and across New Zealand.

A subduction zone is an area where a tectonic plate dives or “subducts” beneath an adjacent tectonic plate. This type of fault is responsible for causing some of the world’s most powerful earthquakes, which occur when areas of built-up stress between the plates rupture.

Slow slip events are similar to earthquakes, as they involve more rapid than normal movement between two pieces of the Earth’s crust along a fault. However, unlike earthquakes (where the movement occurs in seconds), movement in these slow slip events or “silent earthquakes” can take weeks to months to occur.

The GPS network detected the slow slip events occurring on the Hikurangi subduction zone plate boundary in the weeks and months following the Kaik?ura earthquake. The slow slip occurred at less than 9 miles deep below the surface (or seabed) and spanned an area of more than 6,000 square miles offshore from the Hawke’s Bay and Gisborne regions, comparable with the area occupied by the state of New Jersey. There was also a deeper slow slip event triggered on the subduction zone at 15-24 miles beneath the Kapiti Coast region, just west of New Zealand’s capital city Wellington. This deeper slow slip event near Wellington is still ongoing today.

“The slow slip event following the Kaik?ura earthquake is the largest and most widespread episode of slow slip observed in New Zealand since these observations started in 2002,” Wallace said.

The triggering effect was probably accentuated by an offshore “sedimentary wedge” — a mass of sedimentary rock piled up at the edge of the subduction zone boundary offshore from the North Island’s east coast. This layer of more compliant rock is particularly susceptible to trapping seismic energy, which promotes slip between the plates at the base of the sedimentary wedge where the slow slip events occur.

“Our study also suggests that the northward traveling rupture during the Kaik?ura quake directed strong pulses of seismic energy towards the North Island, which also influenced the long-distance triggering of the slow slip events beneath the North Island,” said Yoshihiro Kaneko, a seismologist at GNS Science.

Slow slip events in the past have been associated with triggering earthquakes, including the magnitude 9.0 Tohoku earthquake that struck Japan in 2011. The researchers have also found that the slow slip events triggered by the Kaik?ura quake were the catalyst for other quakes offshore from the North Island’s east coast, including a magnitude 6.0 just offshore from the town of Porangahau on Nov. 22, 2016.

Although scientists are still in the early stages of trying to understand the relationships between slow slip events and earthquakes, Wallace said that the study results highlight additional linkages between these processes.