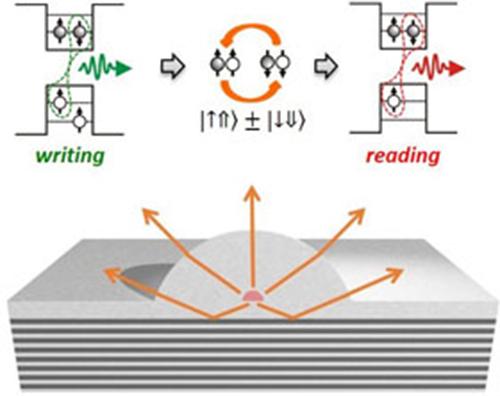

The schematic illustrates the microlens device to measure dark excitons in a quantum dot. The left diagram depicts the spin-blockaded biexciton state that relaxes into a dark exciton and produces a photon; solid circles are electrons while empty ones are holes. The dark exciton then undergoes precession. To read the dark exciton, an extra charge carrier is introduced — in this case, a spin-down electron. Image: Tobias Heindel

To build tomorrow’s quantum computers, some researchers are turning to dark excitons, which are bound pairs of an electron and the absence of an electron called a hole. As a promising quantum bit, or qubit, it can store information in its spin state, analogous to how a regular, classical bit stores information in its off or on state. But one problem is that dark excitons do not emit light, making it hard to determine their spins and use them for quantum information processing.

In new experiments, however, not only can researchers read the spin states of dark excitons, but they can also do it more efficiently than before. Their demonstration, described in APL Photonics, from AIP Publishing, can help researchers scale up dark exciton systems to build larger devices for quantum computing.

“Large photon extraction and collection efficiency is required to push experiments beyond the proof-of-principle stage,” says Tobias Heindel of the Technical University of Berlin.

When an electron in a semiconductor is excited to a higher energy level, it leaves behind a hole. But the electron can still be bound to the positively charged hole, together forming an exciton. Researchers can trap these excitons in quantum dots, nanoscale semiconductor particles whose quantum properties are like those of individual atoms.

If the electron and hole have opposite spins, the two particles can easily recombine and emit a photon. These electron-hole pairs are called bright excitons. But if they have the same spins, the electron and hole cannot easily recombine. The exciton can’t emit light and is thus called a dark exciton.

This darkness is part of why dark excitons are promising qubits. Because dark excitons cannot emit light, they can’t relax to a lower energy level. Therefore, dark excitons persist with a relatively long life, lasting for over a microsecond — a thousand times longer than a bright exciton and long enough to function as a qubit.

Still, the darkness poses a challenge. Because the dark exciton is closed off to light, you can’t use photons to read the spin states — or any information a dark exciton qubit may contain.

But in 2010, a team of physicists at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology figured out how to penetrate the darkness. It turns out that two excitons together can form a metastable state. When this so-called spin-blockaded biexciton state relaxes to a lower energy level, it leaves behind a dark exciton while emitting a photon. By detecting this photon, the researchers would know a dark exciton was created.

To then read the spin of the dark exciton, the researchers introduce an additional electron or hole. If the new charge carrier is a spin-up electron, for example, it combines with the spin-down hole of the dark exciton, forming a bright exciton that quickly decays and produces a photon. The dark exciton is destroyed. But by measuring the polarization of the emitted photon, the researchers can determine what the dark exciton’s spin was.

Like in the 2010 experiments, the new ones measure dark excitons inside quantum dots. But unlike the earlier study, the new experiments use a microlens that fits over an individual quantum dot that was selected in advance. The lens allows researchers to capture and measure more photons, crucial for larger-scale quantum information devices. Their approach also lets them choose the brightest quantum dots to measure.

“This means we can detect more photons of the related exciton states per time, which allows us to access the dark exciton spins more often,” Heindel says.

Measuring the dark exciton spins also reveals the frequency of its precession, an oscillation between a state in which the spins are either up or down. Knowing this number, Heindel explained, is needed when using dark excitons to generate quantum states of light that are promising for quantum information applications. For these states, called cluster states of entangled photons, the quantum mechanical properties are preserved even if parts of the state are destroyed — needed for error-resistant quantum information systems.

Source: American Institute of Physics