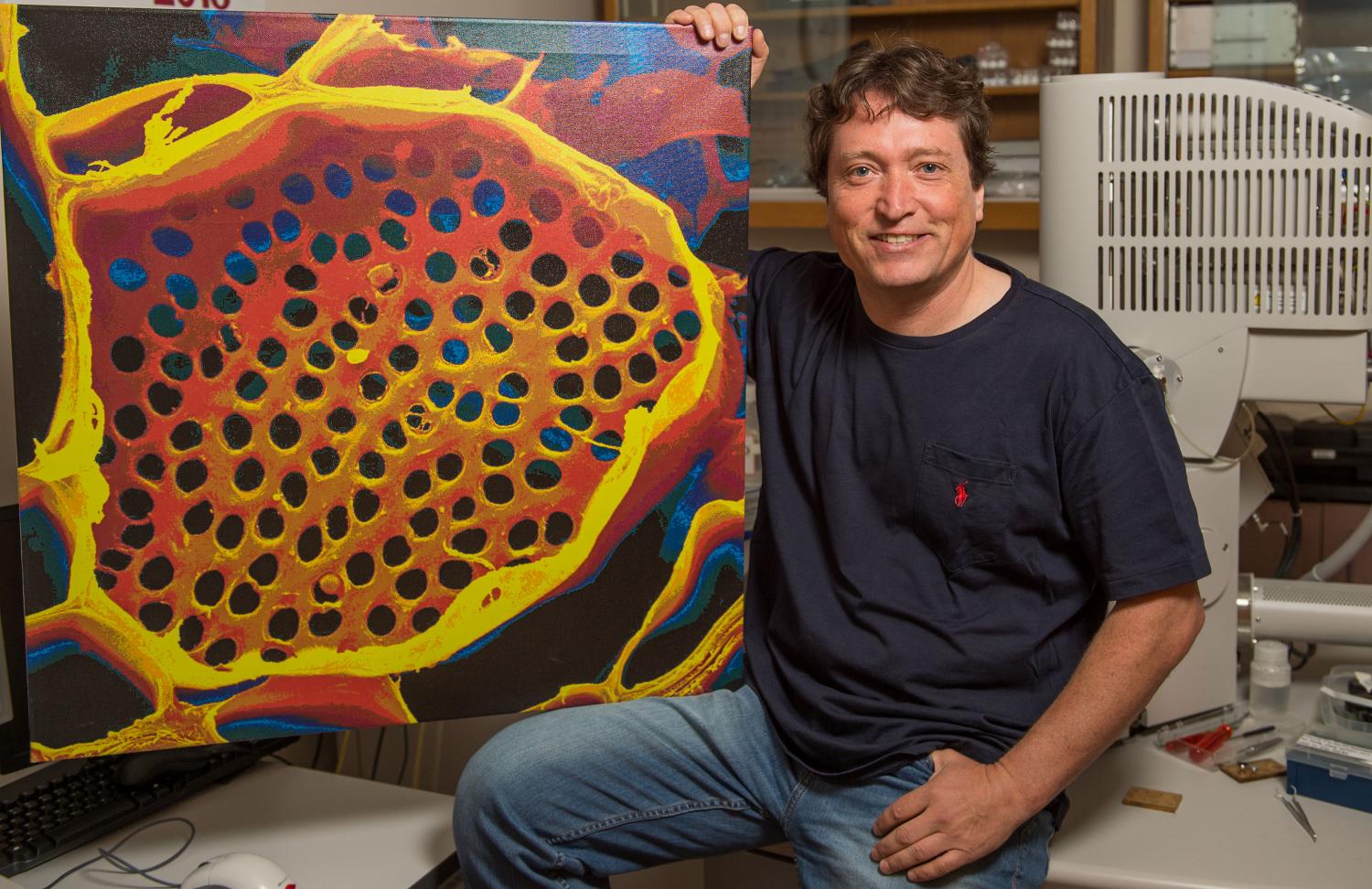

Washington State University biologist Michael Knoblauch sits with a microscope photo of a sieve plate that separates the elongated cells of a plant’s vascular system. (Credit: Washington State University)

Washington State University biologist has found what he calls “very strong support” for an 86-year-old hypothesis about how nutrients move through plants. His two-decade analysis of the phenomenon has resulted in a suite of techniques that can ultimately be used to fight plant diseases and make crops more efficient.

Some 90 percent of the food we consume at one time went through a plant’s phloem, the vascular system that carries sugars and other nutrients from leaves, where they are produced by photosynthesis, to roots and fruits. But scientists know so little about how this works, said Michael Knoblauch, professor in the WSU School of Biological Sciences, that they’re like cardiologists who haven’t learned about the heart.

“If you have a little-supported hypothesis that is central to plant function, it’s a problem,” he said. “For example, take plant-insect interactions. Aphids feed on the system. If we don’t understand how the system works in detail, we cannot find new strategies to kill aphids. Plant viruses also move through the system.”

The fundamental principle of phloem transport was published by Ernst Münch in 1930. While his hypothesis is intuitive and elegant, it does not appear to account for the extreme pressure needed to move fluid in something as large as a tree. Münch left that to others to figure out.

“He came up with the hypothesis because he knew how solute-driven flow could work,” said Knoblauch. “But he was not into measuring all these things or finding evidence for his hypothesis.”

To make his finding, published in the journal eLife, Knoblauch spent more than 20 years devising ways to look inside a living plant without disrupting the processes he was trying to measure and describe.

“It’s super-tough to work with this tissue,” he said. “It’s a technical question. It’s really difficult to access it and this has always fascinated me.”

He measured flow velocities with fluorescent dies and radioactive isotopes. With his son, Jan, a second author on the paper and a WSU sophomore, he developed a “picogauge” that could measure extremely sensitive phloem pressures.

He looked at tomatoes, fava beans, kelp off the British Columbia coast and a red oak in the Harvard Forest in central Massachusetts. With various microscopes—he directs WSU’s Franceschi Microscopy and Imaging Center—he measured the circumferences of not only plant stems but the ciabatta-like holes of sieve plates that separate elongated cells in the phloem tissue.

The cell geometries were particularly critical, as an order-of-magnitude change in the diameter of a tube or hole creates a four-order change in the volume delivered to the roots or fruits.

For his eLife studies, he made roughly 100,000 measurements in each of three morning glory plants he grew alongside WSU’s five-story Abelson Hall.

In addition to building the evidence for a long-held hypothesis, Knoblauch hopes his work can find new ways to protect plants. It might also lead to ways of making the energy in biofuels easier to concentrate and access.

“If we can tell the phloem, ‘OK, store it here, where we can easily harvest it,’ it will be a big step forward,” he said.