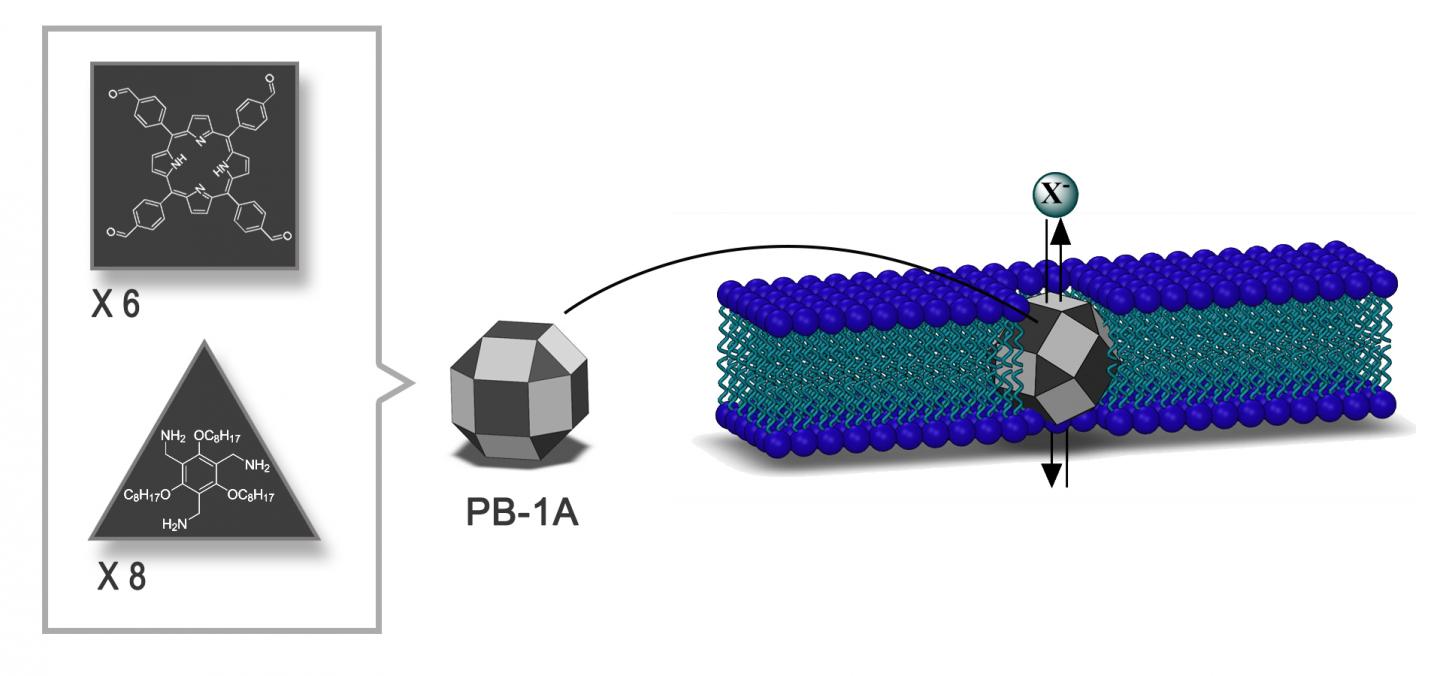

PB-1A design follows the shape of 26-faced polyhedron made of triangles and squares (dark gray) with 12 faces left empty as windows (light gray) for ions to pass through. It has a diameter of 3.64 nm and the right chemical features to fit the cellular membrane. Source: IBS

Exchange of iodide (iodine ions) between bloodstream and cells is crucial for the health of several organs and its malfunctioning is linked to goiter, hypo- and hyperthyroidism, breast cancer, and gastric cancer. Researchers at the Center for Self-Assembly and Complexity, within the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) have devised nanostructures that function as channels for iodide transport in cell membranes. This study, published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS), may lead to diagnosis and treatment of iodide transport disorders.

A protein known as a sodium/iodide symporter (NIS) mediates the transport of iodide from the bloodstream into thyroid cells as well as other tissues, including mammary glands during lactation, cancerous breast tissues, and lacrimal glands. NIS is a hollow structure spanning the height of the cell membrane through which iodide can move into the cells.

IBS scientists developed synthetic ion channels that selectively allow the passage of negatively-charged ions, especially iodides. With a diameter of 3.64 nm and the right chemical characteristics, these channels called porphyrin boxes 1A (PB-1A), fit into the cellular membrane.

PB-1A has the shape of a 26-faced polyhedron made of triangles and squares, named rhombicuboctahedron by Archimedes. Two types of molecules make up 14 faces of the solid, while the other faces are left empty for the ions to pass through.

PB-1A has the advantage of being chemically stable in aqueous solution and in the cell membrane. IBS scientists found that PB-1A naturally inserts itself into the cell membrane, is functional as an ion channel, and non-toxic to cells.

The team observed that different types of negatively-charged ions can go through PB-1A, but some can do it better than others. For example: iodide transfer about 60 times more efficiently than chloride, the most abundant biological negatively-charged ion, that is twice more selective than previously reported channels. The team observed that different types of negatively-charged ions can go through PB-1A, but some can do it better than others. For example: iodide transfers about 60 times more efficiently than chloride, the most abundant biological negatively-charged ion, which is twice more selective than previously reported channels. This difference in efficiency is related to the water molecules surrounding the ions and the energy required to pull out them out, i.e. it is easier for iodide to remove these water molecules as it goes through the channel, which facilitates its passage.

Designing channels with high selectivity for specific ions is not a trivial task. “We are excited by these findings, because in comparison with studies on chloride channels and channels that transport positively-charged ions, iodide-selective artificial channels have been rarely reported in the last decade. Moreover, channels that mimic the functions of NIS are very interesting, as they have the potential to treat thyroid and non-thyroid malignancies,” points out Dr. ROH Joon Ho, one of the corresponding authors of this study.

In the future, IBS researchers aim to develop smart synthetic ion channels gated by light.