For burn victims, the healing process can be excruciatingly painful. Nurses must regularly remove staples and stitches, clear away dead skin, clean the wounds, and determine if the healing process is moving along properly. This process, known as wound care, is often described as just as painful as experiencing the burn itself.

Narcotic drugs are typically given to burn victims to help get them through this process, but often this is not enough to mask the intense pain.

To combat this problem, researchers at University of Washington Human Interface Technology Laboratory have developed an immersive virtual reality (VR) experience designed specifically for burn victims. The technology is currently being utilized at Harborview Burn Center, Shriners Children’s Burn Center, as well as several other burn centers and burn-focused research laboratories, and has been shown in numerous research studies to reduce pain levels significantly.

The VR experience, known as SnowWorld, features a snowy scene where users score points by throwing snowballs at snowmen, penguins, woolly mammoth and flying fish. To play the game, users point their head slightly in the direction they want to throw a snowball and then press a button to launch it.

A scene from SnowWorld.

SnowWorld was designed around the concept of snow because cold and ice is the antithesis to burning fire, said Hunter Hoffman, Ph.D, one of the original creators of SnowWorld.

“We wanted the patients to not think about the accident that caused the fire during their wound care—some even have PTSD regarding this,” said Hoffman, in an interview with R&D Magazine. “That is not going to help their pain level, and it may be difficult psychologically. SnowWorld is pleasant and beautiful. We also have to take into consideration that these are not gamers with full cognitive abilities; these are burn patients that are heavily medicated and are also in pain, so it has to be a simple game for them to be able to even do it.”

The beginning

Hoffman has been investigating the potential for VR for pain reduction since the early 1990s. His interest spiked while he was working with Thomas A. Furness, Ph.D., the Founding Director of the Human Interface Technology Lab. Furness invented the first personal eyewear display, and was marketing the device through his company Virtual Vision. The device, which allowed users to watch movies or play video games via an eyewear headset, was supposed to be geared toward the general consumer, but it was dentists who showed the most interest instead.

“Dentists were buying it to distract their patients during painful procedures,” said Furness, in an interview with R&D Magazine. “Kids could play video games while at the dentist and not complain as much. That’s when we realized there was a market and that this was an amazing distraction for pain.”

Through a mutual friend, Hoffman connected with David Patterson, Ph.D, who studies psychological techniques for reducing severe acute burn pain of patients at Harborview Burn Center in Seattle. Together the two came up with the concept of SnowWorld. The current version of the VR experience was built by Ari Hollander and Howard Rose of Firsthand Technology.

Hoffman then collaborated with Jeff Magula to build a VR system that could be used during the water treatment that burn victims often undergo to soften scar tissue, and remove dead skin.

Because electronics cannot be safely used in water, this system features a custom fiberoptic VR helmet that carries light to the patients’ eyes via a light pipe. This system has also been used for study purposes, as it can provide VR to patients undergoing MRI scans of their brains and demonstrate how the experience is influencing pain response.

A patient uses VR designed for use in water during treatment for burns. Credit: University of Washington

These studies have yielded extremely exciting results, said Hoffman.

“We’ve been really pleasantly surprised how well VR has been able to compete with incoming pain signals,” he said.

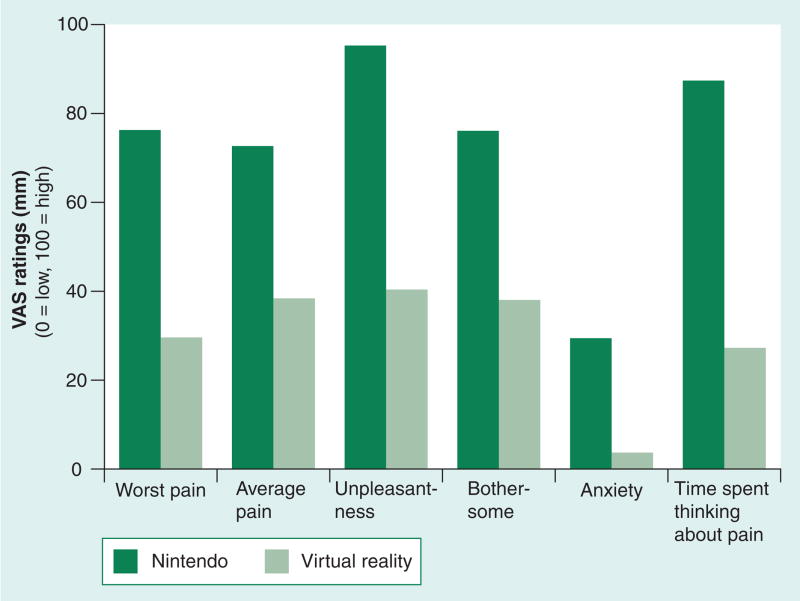

The team published their first study in the medical journal Pain in 2000, which demonstrated the benefit of SnowWorld VR versus standard video games to significantly reduce various subjective pain and anxiety ratings in a patient undergoing bedside burn wound care. (Figure 1).

Source: PubMed

Since then, they have published numerous studies confirming the efficacy of SnowWorld in reducing pain for burn victims undergoing wound care and other procedures.

One study, published in 2007, assessed the efficacy and side effects of immersive VR distraction analgesia, as well as patient factors associated with VR analgesic efficacy in burn patients who require passive range-of-motion (ROM) physical therapy. The study included 88 subjects, 75 percent who were children ages six to 18 years. Compared with standard analgesic treatment alone, the addition of VR distraction resulted in a 20 percent reduction in subjective pain ratings for worst pain intensity, a 26 percent reduction in unpleasantness, and a 37 percent reduction in time spent thinking about pain.

Another study, published in 2008, looked at 11 hospitalized inpatients ages 9 to 40 years who had their burn wounds debrided and dressed while partially submerged in the hydrotank. Each patient spent three minutes of wound care with no distraction and three minutes of wound care in VR during a single wound care session.

Patients reported significantly less pain when distracted with VR, with “worst pain” ratings during wound care dropping from “severe” to “moderate.” The six patients who reported the strongest illusion of “going inside” the virtual world reported the greatest pain reduction effect of VR, dropping from “severe pain” with no VR to “mild pain” during VR.

How it works

VR works in this setting because it reduces the brain’s concentration on the pain, said Furness.

“In order to experience pain you have to be conscious of pain,” he said. “The brain is amazing. In a battlefield situation, for example, a soldier can be critically injured but not notice it because he is so busy, or in a case of an automobile accident, a person can do superhuman things when they have a broken leg because they are focused on just surviving—it is all about distraction. If we give them something to concentrate on that is immersive and that is consuming, then it takes away from what is going on around them.”

In a sense, VR analgesia is similar to the concept of using traditional anesthesia to block out pain, said Hoffman.

“What we are doing is luring the spotlight of attention into the virtual world, so patients, instead of looking at their wounds and watching it and being there in the hospital room, they are now in SnowWorld and are basically less present in the hospital room,” he explained.

The benefits also go beyond just the patient’s perceived pain experience.

Brain scans on patients playing VR while experiencing pain have shown a reduction in pain-related brain activity. This demonstrates that not only is the VR changing how the patient is interpreting the incoming pain signal, it is actually changing the way the brain processes the pain signal, said Hoffman.

“Approximately one-fourth of the brain is devoted to processing visual information—the visual cortex,” said Hoffman. “When someone is in VR they are using up a lot of additional resources and that leaves limited attention available to process the incoming pain signal.”

The impact of technological advances

When the team at the University of Washington first began investigating VR for pain reduction, it was not something that most people were aware of and the technology was difficult to acquire and expensive. For their purposes, a wide field of vision helmet worked best, but when they first started, these devices cost $35,000. Today, thanks to advances in technology, wide field of vision goggles can be purchased for between $500 to $800.

“This was a long time coming,” said Furness. “I’ve been working on this stuff for 52 years and I thought we’d be way further along than we are. The problem was that at the time we just didn’t have the hardware or the technology. We could do it, and we knew the power of it a long time ago, but it was really expensive to get high quality, and even that quality wasn’t that great. We knew what we had to build but it required an economy of scale, it required the pull to bring the technology along. That pull came from the need for higher performance computing in laptops, and eventually, smart phones.”

As a result, SnowWorld has been updated. The team published the first paper on the use of Oculus Rift goggles for any clinical applications in 2014. They have also made a new version of SnowWorld that is designed to be used with Oculus Rift and HTC Vive helmets and are working to incorporate these new helmets into wound care treatment for burn patients.

“We have been predicting that this is going to happen and at the same time we were surprised that it has happened,” said Hoffman. “The recent developments, especially in 2015, 2016, and 2017, are very exciting and intense.”