By Gordon Feller

In a report charting, “The Rise of Innovation Districts,” the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., lists Barcelona alongside seven other cities that contain such districts, the others being Berlin, London, Medellin, Montreal, Seoul, Stockholm, and Toronto. How exactly did an ancient Catalonian city, situated on the coast of Spain, manage to pull this off?

In a report charting, “The Rise of Innovation Districts,” the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., lists Barcelona alongside seven other cities that contain such districts, the others being Berlin, London, Medellin, Montreal, Seoul, Stockholm, and Toronto. How exactly did an ancient Catalonian city, situated on the coast of Spain, manage to pull this off?

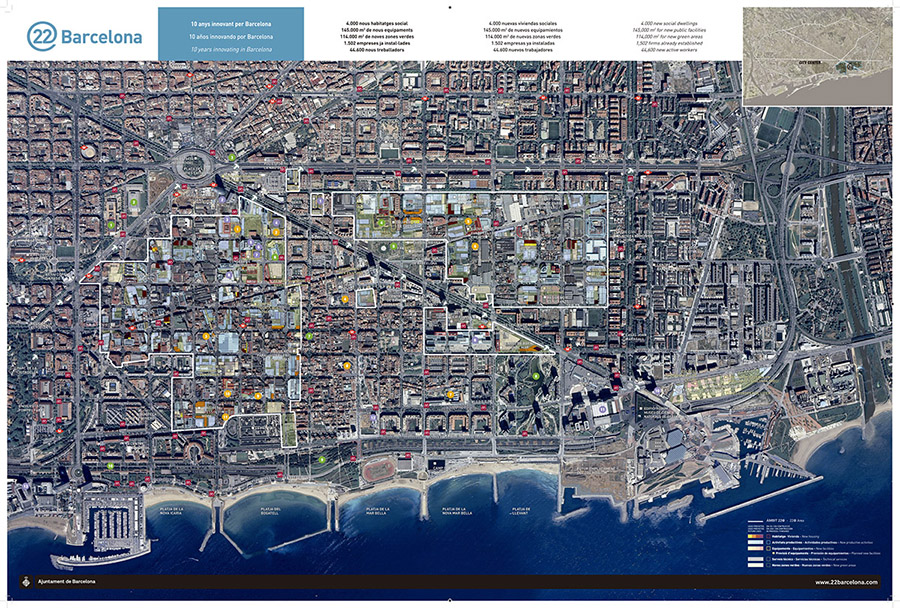

The modern-day R&D district now known as 22@Barcelona was propelled by unique opportunity: to transform the section of Barcelona that had long been known as Poblenou. The Ajuntament de Barcelona, a section of the Barcelona City Council, recognized one of the key facts of the city’s long history: As Barcelona’s old textile and chemicals district, Poblenou had long been dedicated to industrial production. Before any shift occurred in this urban neighborhood, Poblenou’s leaders and residents longed to achieve one goal over 20 years of concerted effort — to create a district that serves as an ‘innovation platform,’ situated within the global knowledge economy.

A vigorous debate began amongst Barcelona residents in the late 1990s. It was a political tussle about an untapped asset: regenerating Poblenou’s 200 hectares of obsolete industrial zone. Two opposing objectives were being pushed by a broad spectrum of activists, city planners, government executives, investors and lenders, plus numerous other parties. Either a regeneration which preserves the area’s productive industrial heritage or a transformation of the residential area, in response to the rising scarcity of social housing in Barcelona.

Despite this confrontation, or perhaps because of it, a mixed solution was adopted in 1998. The decision was made to create a ‘compact city district,’ and for it to be one where knowledge-based firms would work side-by-side with residences. The year 2000 saw the approval of the plan: “Modification of the General Metropolitan Plan for Transforming Poblenou Industrial Areas, District of Activities 22@.” With this move, Barcelona bet decisively to preserve the older profile of this area, but also to combining residential uses.

To better understand how and why 22@Barcelona has succeeded, we interviewed one of the districts most important leaders, Dr. Josep M. Pique, president of The Triple Helix Association. As Pique recalls it, his city’s “elected and appointed executives made a special effort to look ahead, and to do so in a way that stretched their minds much more than a few years into the future.” With concrete plans in hand, they looked ahead, “towards an urban transformation which, over time, has progressively regenerated the industrial area. The choice was made to avoid the conventional approach, which uses demolition to completely change the urban environment. A different process was developed, with the aim of establishing a balance that allowed for re-defining the new urban form in continuity with earlier forms.”

With this idea at the center of a massive program, Barcelona started neighborhood transformation projects. They knew that it was not going to be easy, especially since for more than a hundred years Poblenou’s main economic engine was heavy industry. But over two decades, Poblenou has been turned into an award-winning model for science-technology R&D and design. It continues to succeed today by encouraging collaboration and synergies between all the key actors: universities, government agencies, private companies, non-profits and associations. The result is a high-level of company formation and entrepreneurship which is linked to the creation of a decent quality of life for residents and commuters.

History offered some lessons to the activists and the officials (elected/appointed) who spear-headed the project. During the second half of the 19th century, and on into the first half of the 20th century, textiles reigned supreme, with later moves into mechanical, chemical and food industries. In the 1960s, the decay of the area began. This process intensified during the economic crisis of the 1970s and 1980s. As the history was described by Pique, “the 1992 Olympic Games saw the construction of the Olympic Village, with ring roads around Barcelona. The recovery of the Mediterranean city beaches coincided with the opening of The Diagonal — Barcelona’s broadest and most important avenue. The capstone was the construction of the high-speed train station at Sagrera.”

History offered some lessons to the activists and the officials (elected/appointed) who spear-headed the project. During the second half of the 19th century, and on into the first half of the 20th century, textiles reigned supreme, with later moves into mechanical, chemical and food industries. In the 1960s, the decay of the area began. This process intensified during the economic crisis of the 1970s and 1980s. As the history was described by Pique, “the 1992 Olympic Games saw the construction of the Olympic Village, with ring roads around Barcelona. The recovery of the Mediterranean city beaches coincided with the opening of The Diagonal — Barcelona’s broadest and most important avenue. The capstone was the construction of the high-speed train station at Sagrera.”

The process kicked into high gear in 2000 with an initial phase of urban renovation and high-quality infrastructures. In 2004, 22@Barcelona several strategies were developed and deployed. According to Dr. Pique, “these aimed to create, within the district, a set of ‘Urban Clusters of Innovation.’ These were focused on various emerging sectors which Barcelona prioritized for the city‘s next economy.” There were four sectors: media, medical technologies, energy, and information/communication technologies. In some cases, these sectors were already present, while in some others, such as medical technologies and energy; they were making a bet that it was possible to attract them into the city. In 2009, design was added to the list of four categories.

Approximately 70% of the Poblenou industrial area has been renovated over the past decade. 22@Barcelona has approved 150 “urban transformation” plans, of which 141 have been executed by investors from the private sector. The approved plans account for a total of 3,029,106 m² of floor space. This is more than 140,000 m² of land for facilities plus nearly 1,600 housing units with some sort of public subsidy.

The district’s regeneration has led to the establishment of 10 university campuses. They host a total of more than 25,000 students, plus 12 R&D and technology transfer centers. The most recent census of businesses in 22@Barcelona demonstrated that, despite the pandemic’s forced building closures, there is still continued growth.

According to the most recent 22@Barcelona Business Census, more than 8,223 companies are located inside 22@Barcelona, directly employing 93,000 workers. The total turnover of the companies inside the district is 10,300 million Euros, of which 32.3% are knowledge-based companies. An additional 27.4% are export-focused companies. A total of 40.4% of the companies are related to the district’s various clusters.

According to the most recent 22@Barcelona Business Census, more than 8,223 companies are located inside 22@Barcelona, directly employing 93,000 workers. The total turnover of the companies inside the district is 10,300 million Euros, of which 32.3% are knowledge-based companies. An additional 27.4% are export-focused companies. A total of 40.4% of the companies are related to the district’s various clusters.

Among the lessons learned in Barcelona, several stand out as relevant for similar projects located anywhere else in the world:

A vibrant city offers a superb foundation for developing a knowledge-based economy. Cities are the premier platform for any knowledge-based economy because they are, in essence, talent platforms. Humans are the raw material for the new economy. If a district wants to attract, retain and create talent, their host cities must provide a great place for learning, working, playing and living. The cities are a place for learning new applications, which means that urban environment can be used as a living lab in ways that enable someone to “learn locally to compete globally.”

Both greenfield and brownfield developments create ‘innovation ecologies’ linking each of the various ‘agents of change’ — universities, industries, governments. Their starting points may be quite different, but the vision emphasizes the knowledge-based economy. To succeed with their district projects, cities have learned that they must take full advantage of each agent’s capabilities.

Larger-scale urban revitalization needs an integrated approach, one that includes a pivot toward urban infrastructure renewal, a smart business and economic strategy, a laser-focus on talent and the human dimension and a solid foundation provided by smart governance.

Clear leadership by the government is necessary, especially to create a successful innovation district. In some cases, it may be the city’s mayor, and in others it may be at the regional or national level. The involvement of universities and associations will help to generate the vision — and create trust in the project. Without clear rules about land-use, and without clear vision about the type of district, it will be difficult to advance the transformation process.

Tell Us What You Think!